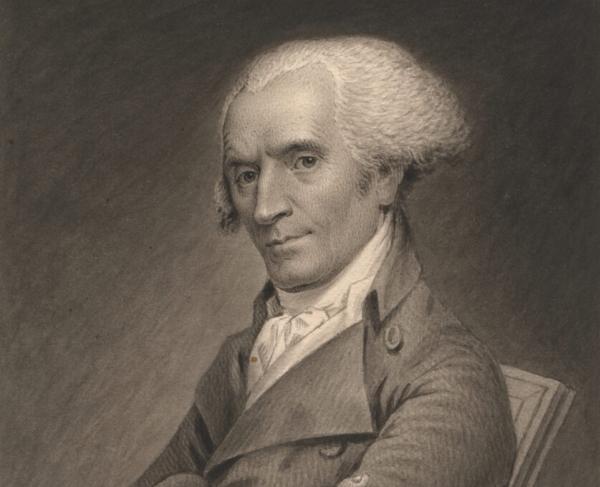

Albert Gallatin

Born in Geneva as Abraham Alfonse Albert de Gallatin in 1761, Albert Gallatin descended from a long line of Gallatins who had served the Swiss republic for centuries. His parents died when he was young, but Gallatin still retained his family’s penchant for public service. After a rich early education, he attended what is now the University of Geneva and graduated in 1779. Rather than look for employment in Europe, Gallatin emigrated to the United States the following year at the age of 19. During his early years in America, he taught French at Harvard, worked as a land surveyor, and tried to encourage more Swiss to come to his adopted country.

In 1785 Gallatin officially became a U.S. citizen. After briefly living in Virginia, he purchased a 400-acre plot in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, and built a stone house which he named Friendship Hill. He married Sophie Allègre on May 14, 1789, much to her mother’s dismay. Unfortunately, Sophie died of illness just five months later and was buried (at her own request) in an unmarked grave on Friendship Hill. After years of mourning, Gallatin and met Hannah Nicholson, daughter of Revolutionary War naval hero James Nicholson. The two married in 1793 and had six children.

Meanwhile, Gallatin’s bent toward public service pulled him into American politics. In 1788, he served as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional convention. He was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives two years later and to the State Senate in 1793. In 1795, Gallatin won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Republican.

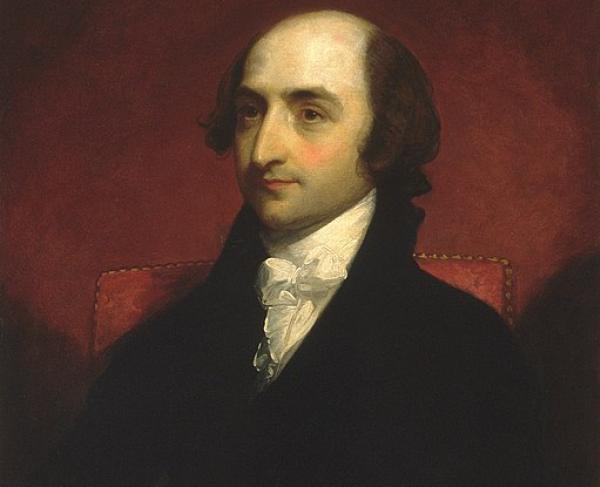

After two years in Congress, Gallatin emerged as a leader of the minority party. He harbored serious concerns about Alexander Hamilton’s management of the U.S. Treasury and economic policies more broadly. Gallatin believed Hamilton’s system was ripe for government excess and corruption. He played a key role in establishing what is now known as the House Ways and Means Committee as a tool to reign in government spending and holding the Executive branch accountable. This opposition to “big government” made him a natural ally for Hamilton’s rivals, namely Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Gallatin became a respected a voice on financial policy. In 1801, newly-elected president Jefferson appointed Gallatin as Secretary of the Treasury. When Madison won the presidency in 1808, Gallatin remained as treasury secretary. Over his 11 years as head of the Treasury Department, Gallatin financed the Louisiana Purchase and oversaw dramatic reduction in U.S. debt.

When the War of 1812 began, Madison selected Gallatin—a native French speaker—to represent the United States in St. Petersburg as part of a negotiating team that included Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. Gallatin played a key role in finding consensus amongst the outspoken and opinionated members of the delegation. In 1814, the negotiators and their British counterparts moved to Ghent, Belgium, where, for the next five months, they hammered out a peace agreement, the Treaty of Ghent. According to Adams, Gallatin provided “largest and most important share to the conclusion of the peace.”

After the war, Gallatin declined the offer to return to the cabinet. He was instrumental in persuading Congress to charter the Second Bank of the United States. He later accepted an appointment as ambassador to France and resided in Paris from 1816 to 1823. During that time he assisted in negotiating the Bagot-Rush Treaty and the Treaty of 1818, thus resolving outstanding issues from the War of 1812. After a brief interest in the vice presidential nomination in 1824, Gallatin returned to Europe in 1826 as ambassador to Great Britain until 1827.

Gallatin moved to New York City in 1828 and remained there for the duration of his life. Though no longer an elected official, Gallatin weighed in on political matters. He was a vocal critic of President James K. Polk and wrote a widely-read pamphlet criticizing the Mexican War. During this period, Gallatin played a pivotal role in the foundation of the University of the City of New York—today’s New York University—which was founded in 1831. He also took an interest in Native American affairs, befriended tribal leaders, and wrote two books on Native American history and language. In 1843, the New-York Historical Society elected him as their president. That same year, he co-founded the American Ethnological Society and served as its first president. This, in combination with his study of Native American languages have led many to call Gallatin the “father of American ethnology.”

Albert Gallatin died August 12, 1849, three months after the death of his wife. At the time of his passing, Gallatin was the last surviving member of Jefferson’s cabinet and the last senator who had served in the 18th century.