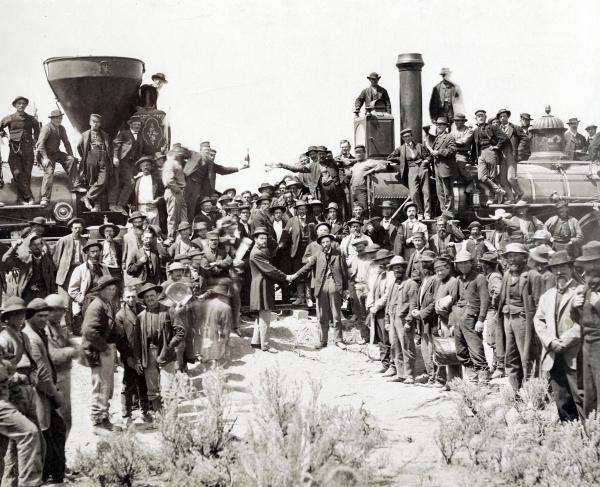

Expansion and Exploration in the New Republic: The Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

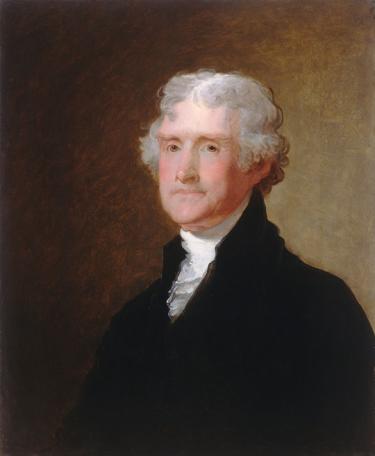

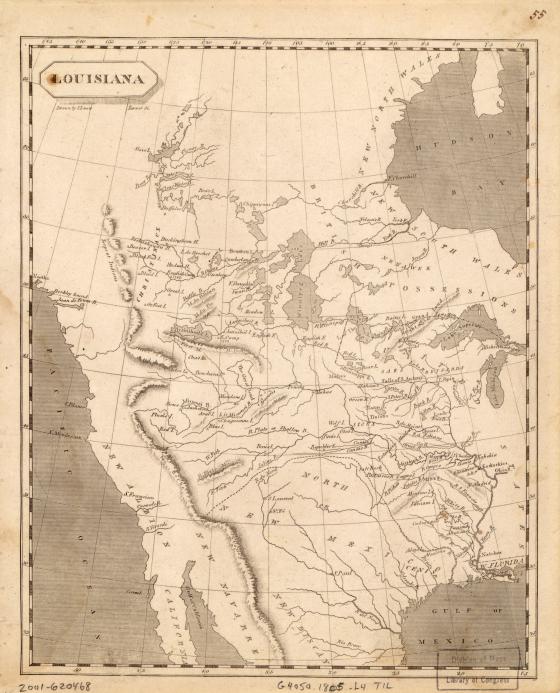

According to eminent historian William J. Fowler, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase by the United States, “was the best deal in real estate since the Garden of Eden.” It’s easy to understand why Fowler would gush so. For 15 million dollars the United States purchased 828,000 square miles between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains at a cost of roughly three cents an acre. It was the greatest achievement of President Thomas Jefferson’s administration and one of the most decisive executive actions in the history of the American Presidency.

When the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution in 1783, the westernmost boundary of the United States was the Mississippi River. Americans living in the interior and on the frontier relied heavily upon the Mississippi River for trade. At the mouth of the Mississippi River stood New Orleans, a port that Americans who used the Mississippi River sorely needed for trade, particularly as a point of export. Throughout the eighteenth century, New Orleans drifted between French and Spanish control. When France controlled New Orleans, they permitted the Americans the “right of deposit” to store goods for export there. Once France ceded control of New Orleans to Spain, however, the Spanish refused to grant Americans the “right of deposit.” This angered many Americans who relied on Mississippi trade for their livelihood and deeply troubled the third American President, Thomas Jefferson, who looked to the American interior as an empire of liberty, where his vision of a society of yeoman gentlemen farmers peacefully tilling the soil could flourish.

By 1803 France was back in control of New Orleans, but the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was cash strapped. A portion of his army had recently been devastated in Haiti by a combination of malaria and the insurgency of Haitian revolutionaries, led by Toussaint L’Oveture. For some time, Napoleon considered a French North American Empire, but after the sequence of events in Haiti, he changed his mind. Initially Jefferson was simply interested in purchasing New Orleans, but when Napoleon offered the American negotiation minister, James Monroe, the whole of the Louisiana Territory, Jefferson happily accepted the deal. It is of interest to note that under Constitutional mandate, only Congress can sign a treaty with a foreign power. Jefferson, in a move that would have made Alexander Hamilton proud, side-stepped the Constitution and ordered his minister to cinch the deal.

The Louisiana Purchase effectively doubled the size of the United States. What would become Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska and parts of present-day New Mexico, South Dakota, Texas, Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado would all eventually emerge from the new territory.

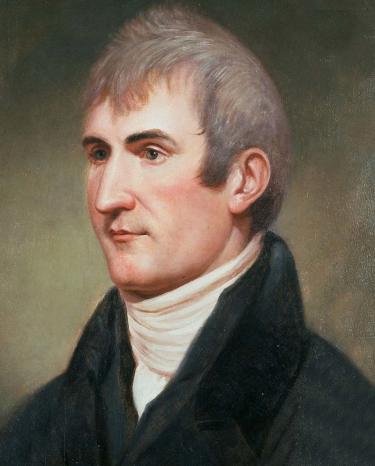

Because of his keen intellectual curiosity and his deep interest in natural history, Jefferson wanted to see for himself exactly what he purchased. One of the greatest explorations in American history followed the Louisiana Purchase, when Jefferson dispatched Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead a band of soldiers, mountain men, natives, and a slave to tour the new territory. Known as the Corps of Discovery, the Lewis and Clark Expedition set out from Saint Louis in 1804 and returned in 1806.

Jefferson directed Lewis and Clark to first and foremost find the elusive Northwest Passage, a body of water believed to connect the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Jefferson also instructed the explorers to record all the plant and animal life they encountered, map the territory, and engage with the Native peoples of the region on friendly terms.

For the most part, the explorers had friendly encounters with various Indian groups. This was partly due to another of the most important individuals to participate in the expedition: a Shoshone woman named Sacagawea, who served as a mediator between Lewis and Clark and the Indian peoples they met.

Sacajawea proved an able ally and in one instance brokered a deal with Indians to get Lewis and Clark much needed horses. Accompanying her was her husband, Pierre Charbonneau, and her infant son, strapped to her back in a papoose.

The party traveled west via the Missouri River using flatboats, small bateaus, and pirogues. When they reached the headwaters of the Missouri in present day Montana, they realized there was no such thing as the Northwest Passage. They had reached the Continental Divide where waters to the East drain into either the Atlantic Ocean of the Gulf of Mexico and waters to the west drain into the Pacific Ocean. Leaving their larger watercraft behind, they portaged for 17 miles across the Continental Divide, carrying with them their small boats, heavy equipment, supplies and gathered specimens. It was a feat of heroic endurance.

The expedition provided information beyond anyone in the East’s wildest dreams. Lewis and Clark were hailed as national heroes upon their return in 1806. During their exploration, Lewis kept a diary, and both men collected samples of flora and fauna that they sent back to Jefferson, either in Washington, DC or at Monticello, his home in Charlottesville, Virginia. The entrance parlor of Monticello is decorated with many items secured during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The animal that most impressed members of the Corps of Discovery were the millions of bison they encountered. A century after Lewis and Clark encountered several million buffalo, the animal almost went extinct in the wake of western settlement. Today the buffalo has recovered after federal protection intervened on the species’ behalf. Their expedition led directly to the opening of the western interior of the United States to settlers.

It is a tragic irony that, the biggest losers as a result of the Louisiana Purchase were the Native Americans, given that Sacagawea, an Indian, had played such a vital role in the expedition. Regardless, the Louisiana Purchase and subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition paved the way for a modern United States, opening for many the amber waves of grain and purple mountain majesty of the Rocky Mountains and beyond.