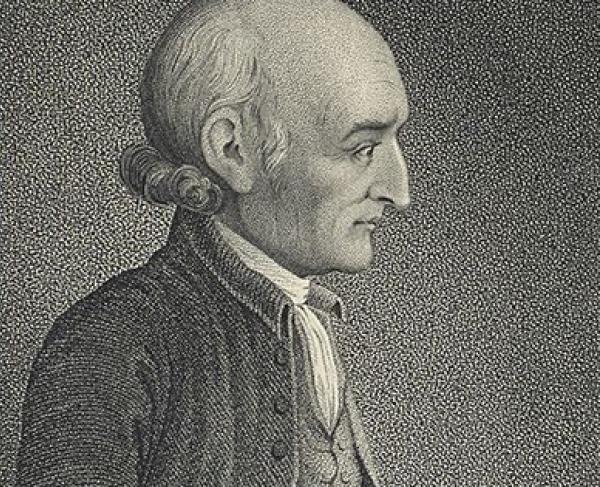

George Wythe

American statesman and revolutionary George Wythe was born in 1726 on his family's plantation in Chesterville near present day Hampton, Virginia. Both of his parents descended from Quaker families, and Wythe adhered to such religious tradition throughout much of his life. His mother, likewise, instilled in him a love of learning at an early age and sent him to grammar school in Williamsburg after his father’s death. Wythe began his legal career in 1746 after studying law in the office of his uncle. After admittance to the bar, he moved to Spotsylvania County, Virginia where he began his own practice under the tutelage of Zachary Lewis. Soon, the young lawyer began courting Lewis’s daughter Ann, and the two married in 1747.

However, upon his wife’s death the following year, a grieving Wythe devoted himself entirely to his work and public service. In October 1748, he secured his first political position as the clerk to two committees in the Virginia House of Burgesses. For the next two decades Wythe held a variety of different offices, serving as one of Williamsburg’s first aldermen and a clerk to the Committee of Correspondence. In 1754, Governor Robert Dinwiddie appointed him acting attorney general while Peyton Randolph travelled to London. The following year, his brother Thomas died allowing Wythe to inherit the family’s Chesterville plantation. However, he continued to live and work in Williamsburg where he married Elizabeth Taliaferro, the daughter of wealthy planter Richard Taliaferro. In 1761, the College of William and Mary appointed Wythe to their Board of Visitors where he mentored a series of legal apprentices and students including Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, Henry Clay, and John Marshall.

As tensions between America and its mother country began to strain, Wythe gained notoriety for his fierce opposition to the British taxation, particularly the Stamp Act. In fact, his contemporaries noted that Wythe’s radical hostility to the legislation betrayed his otherwise reserved and modest demeanor. Nonetheless, the respected Virginia statesman grew to be an ardent revolutionary in the fight for American independence. He attended the Second Virginia Convention as a representative from Williamsburg where he witnessed Patrick Henry declare, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” and succeeded George Washington in the Second Continental Congress when Washington took command of the Continental Army. As part of the Congress, Wythe supported and signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Later that year, Wythe rushed back to Virginia to begin construction on its new state government. He helped approve the state’s seal and motto with George Mason and revise Virginia’s law code with his former student and friend Thomas Jefferson. As Wythe helped build a nation during the Revolution, he leased his Chesterville plantation to local farmer Hamilton Usher St. George, whom Wythe later learned to be a British spy. St. George allegedly aided British raiding parties in laying waste to Williamsburg and the surrounding farms along the James River. Wythe evicted St. George’s wife from Chesterville and returned to the plantation with Elizabeth while American and French forces converged on Virginia in 1781 for the final campaign of the war. The Wythes hosted both General Washington and General Comte de Rochambeau prior to the Siege of Yorktown.

After the war, George Wythe's commitment to his new country never wavered. He secured election as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 where he served on a committee with Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney to determine the convention’s rules. Later that year, he ardently promoted ratification of the Constitution at the Virginia Convention. Though President Washington offered to appoint him a judge on one of the new federal courts, Wythe opted to remain in Virginia on the Court of Chancery. In 1782, he upheld the principle of judicial review in a precedent case to Chief Justice John Marshall’s Marbury v. Madison landmark decision.

In 1805, the now elderly Wythe welcomed his troubled great nephew, George Wythe Sweeney, to live with him. The following year, Wythe caught the seventeen year-old trying to steal some of his books, probably to pay for gambling debts. Nonetheless, Wythe continued to board his great-nephew in his Richmond home. On May 25, 1806, however, Wythe fell gravely ill. Doctors believed the illness to be cholera, but they grew suspicious when Sweeney tried to cash a hundred dollars from Wythe’s bank account two days later. The household cook, who also fell ill, swore she saw Sweeney poison their morning coffee one day. Wythe died on June 8, and officials quickly charged Sweeney with murder. A jury acquitted the boy for arsenic poisoning but convicted him for check forgery in a separate trial. In a great irony, however, Virginia courts overruled Sweeney’s conviction based on a forgery law drafted by George Wythe years prior.