John Parker Boyd

Many readers of history often perceive the successes of great individuals and visionaries as having the most impact on human events, but that is actually not often the case. In fact, the people held to be failures and disgraces can have an impact or influence of their own. Such an individual is John Parker Boyd, whose performance in the War of 1812 helped lead to the entire restructuring of the officer corps in the United States Army, an influence he himself vehemently denied and resented.

Boyd was born in 1764 in the small town of Newburyport in Massachusetts. Though he bore witness to many of the events that led up to the American Revolution, but was too young to serve in the war itself. He would have to wait until 1786, when he finally joined the United States Army as an ensign or junior officer, reflecting at least some family influence or education. He served in the army for three years, most notably during the suppression of Shays’ Rebellion in western Massachusetts, but in his desire to see a little more action, he resigned from his commission and traveled, of all places, to India. At this time, India was broken into several princely states, each one vying for dominance over the other, and many sought to do so by employing European or American officers to modernize their militaries along Western lines. Boyd found employment under the Nizam (prince) of Hyderabad, located in the south-central region of the subcontinent. Though he achieved a position of authority over more than a thousand soldiers, he acquired a habit for recklessness and the largest battle he is known to have fought in was a major defeat for Hyderabad. Still, by the time the British began exerting their influence over the subcontinent, Boyd seemed to have served ably enough to maintain his reputation, and make a good deal of money in the process.

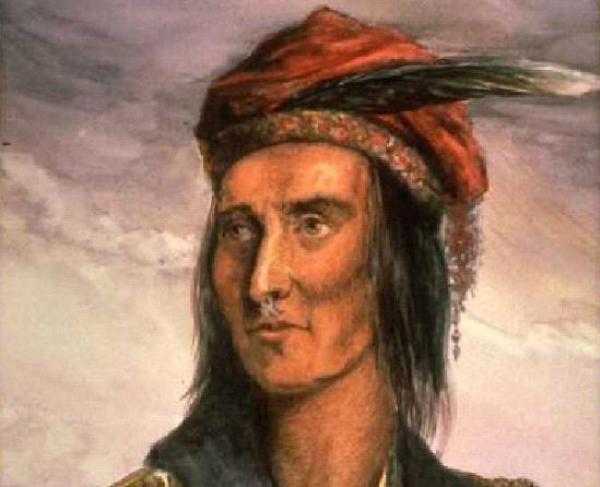

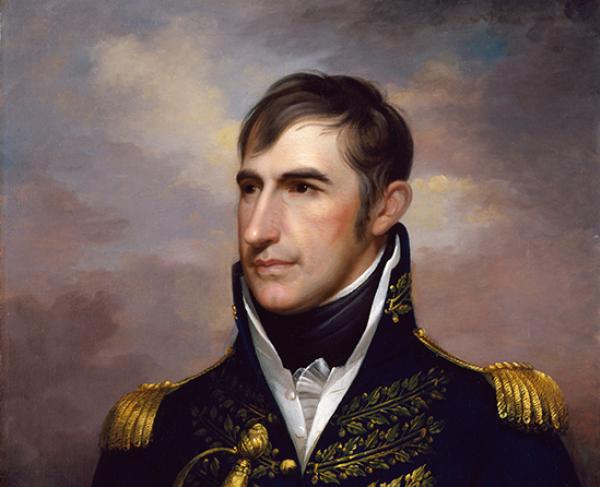

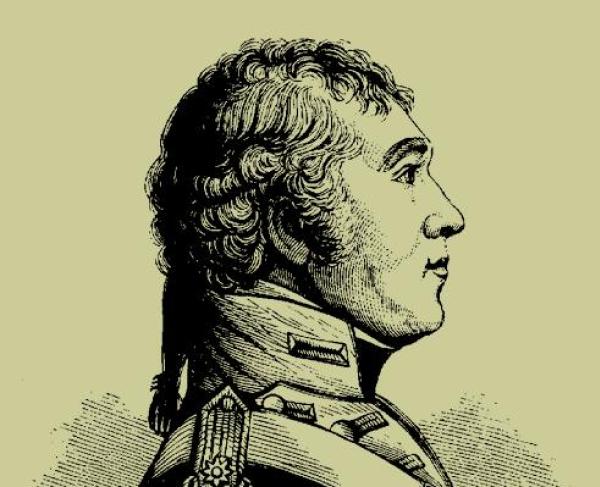

Boyd returned to the United States after selling his command in 1798, and ten years later, rejoined the Army as a colonel ten years later, thanks in part to his Democratic-Republican political connections. He participated in the Battle of Tippecanoe under William Henry Harrison, commanding the 4th U.S. Infantry. Once again, he served well enough to warrant a promotion to Brigadier General when a new war with Britain broke out. Then, disaster broke out. Boyd participated in the invasion of Canada under Revolutionary War veteran James Wilkinson. While on the march to Montreal, the Americans confronted a mixed force of British regulars and Canadian militiamen numbering around 900 at Crysler's Farm. Boyd, eager to sweep the enemy aside and in complete command due to Wilkinson claiming illness, led more than twice that number and ordered an assault. It soon became clear, however, that he had underestimated the resistance, and was also unable to effectively coordinate his infantry with his artillery. The British forced the Americans to retreat, and what should have been an easy victory proved to be a complete debacle. Wilkinson blamed Boyd for the loss and placed him in charge of a winter camp in New York, before ordering him again to join in on another failed assault in 1814, for which he also blamed Boyd. Boyd was relieved of further active duties, but loudly protested his treatment from 1816 onwards. However, John Boyd's ruined reputation also had a profound impact on the U.S. military in its own way. Fellow War of 1812 General Winfield Scott became so frustrated at the practice of granting generalships to political appointees that he began heavily lobbying for improved and modernized officer training. Scott's zeal to prevent disasters like Crysler's Farm by ensuring America had access to a permanent and professional officer corps had a huge impact on the curriculum at West Point.

After the war, Boyd became heavily active in local Boston politics under the Democratic-Republican and Democratic banners, as well as supporting various charitable organizations. Serving on the city council in the 1820’s, President Andrew Jackson appointed him the port’s Naval Officer in 1829. He died one year later and was buried in Christ Church Cemetery. Interestingly, Boyd never married throughout his life, but his will contained provisions for two of his children. One, a boy named Wallace, was Boyd’s son by a woman named Marie Ruppell, and the other, a girl named Frances, was his daughter by a Muslim woman he met in India named “Housina.” Sadly, Boyd’s arbiters never found Housina and Frances, but Wallace changed his name to John after his father’s passing and grew up to become a prominent ship captain in Boston.

Related Battles

189

120