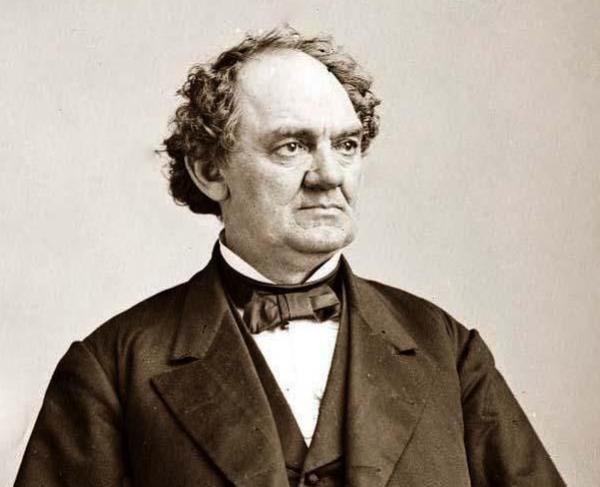

P.T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum’s legacy lives on as one of the greatest American showmen. However, P.T. Barnum’s work in the American political arena is rarely brought to the forefront. Prior to establishing Barnum & Bailey Circus— one of the largest traveling circuses in the United States— Barnum used his passion for entertainment as a platform for political education and outreach during the Civil War.

Before the Civil War, P.T. Barnum reshaped the accessibility and content of popular American entertainment by introducing numerous museums, circuses, and forums accessible to America’s middle and lower class. Before P.T. Barnum, American entertainment consisted of high-brow theatre and opera performances accessed primarily by members of the American elite class. Barnum found the working class’ inaccessibility to popular entertainment unfathomable, as he stated, “men, women and children, who cannot live on gravity alone, need something to satisfy their gayer, lighter moods and hours.” P.T. Barnum changed the game by founding museums and theatre productions that placed family entertainment where “men and women, adults and children, could intermingle safely in the knowledge that no indecencies would assault their senses either on stage or off.” Most importantly, admission to these shows and exhibits was affordable— visitors paid the low price of 25 cents to explore all that Barnum’s American Museum in New York City had to offer.

While Barnum gained traction in reshaping the nature of popular entertainment during the mid 19th century, the political climate of the United States grew more polarizing as the Civil War approached. Barnum was not naive to the intensifying nature of American politics, as his stances on the election of Lincoln in 1860, the secession of the Southern states, and the outbreak of the Civil War were not discreet. In 1855, P.T. Barnum formally switched his allegiance from the Democratic to the Republican Party. Once the Civil War began, Barnum was an ardent supporter of the Union and attended “peace meetings” held primarily in Fairfield and Litchfield Counties in Connecticut. Barnum described the meetings as follows: “It was usual in these assemblages to display a white flag, bearing the word ‘Peace’ above the National flag, and to make and listen to harangues denunciatory of the war.” At these meetings, Barnum vocalized his stance against slavery and alcoholism, and Barnum’s charisma connected him to major politicians in the Northeastern United States.

Barnum’s political ideology was not exclusive to his involvements in political gatherings. In fact, Barnum utilized his American Museum in New York City— a five-story building that housed an aquarium, natural history exhibits, wax figures, a lecture room, and his famous “freak show”— as a means to promote the Union cause. Barnum filled the museum with military paraphernalia and staged patriotic dramas. Due to the museum’s identification with the Northern cause, Confederate agents burned down Barnum’s American Museum in the fall of 1864 as part of their plan to set New York City ablaze.

In addition to his individual contributions to the Civil War cause, members of P.T. Barnum’s freak show had visible ties to Civil War politics. In 1863, P.T. Barnum encouraged the marriage between two of his performers— Tom Thumb and Lavinia Warren— to distract American citizens from the troubles and turmoils that plagued daily lives during the War. Tom Thumb, who stood at three feet four inches, and Lavinia, who stood at two feet eight inches, were both groomed by Barnum in the art of singing, dancing, and miming. Because of their size and their talents, the pair became international celebrities, and their marriage made international headlines even receiving a wedding present from Mary Todd Lincoln.

In 1864, P.T. Barnum encouraged Pauline Cushman, a Union spy, to join his show as a one-woman performer. Cushman’s performances entailed a detailed exaggeration of her role as a Union spy throughout the War, and her performances encouraged morale for the Union cause during the Civil War’s grueling final years.

Even though P.T. Barnum was pro-Union, he signed on Martin Van Buren Bates, “the Kentucky Giant” and Confederate soldier who served in the 5th Kentucky Infantry to join his show in 1865. Standing at an impressive seven feet and nine inches, Van Buren Bates initially returned to his home in Kentucky before migrating to Cincinnati, Ohio to escape rising tensions in the state. Finding his immense proportions as an object of wonder, Bates enrolled himself as one of P.T. Barnum’s “curiosities” in July of 1865 and he traveled with the circus all over the United States and Canada for five years, sometimes performing in his old Confederate uniform.

However, while Barnum used his show and his platforms to support the Union war effort and entertain the United States during the tumultuous Civil War, his shows did market people of color and people with disabilities as “freaks” and “curiosities.” In addition, he commonly exaggerated performers' differences and utilized stereotypes to sell and market many of his performers. Though this incorporation of colored and disabled populations is problematic by modern standards, Barnum provided opportunities for the performers in his shows to find sustainable employment in an America where they endured many barriers.

After the Civil War, Barnum served in the Connecticut state legislature in 1865 and again in the late 1870s. In the legislature, Barnum became a leading advocate for pro-temperance reforms and the abolition of the death penalty. Barnum’s passion for political involvement is exemplified in his following quote: “It always seemed to me that a man who “takes no interest in politics” is unfit to live in a land where the government rests in the hands of the people. Consequently, whether I expressed them or not, I always had pronounced opinions upon all the leading political questions of the day, and no frivolous reason ever kept me from the polls.” Barnum took a stand on pressing political issues until his death on April 7, 1891. Barnum is buried in his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut.