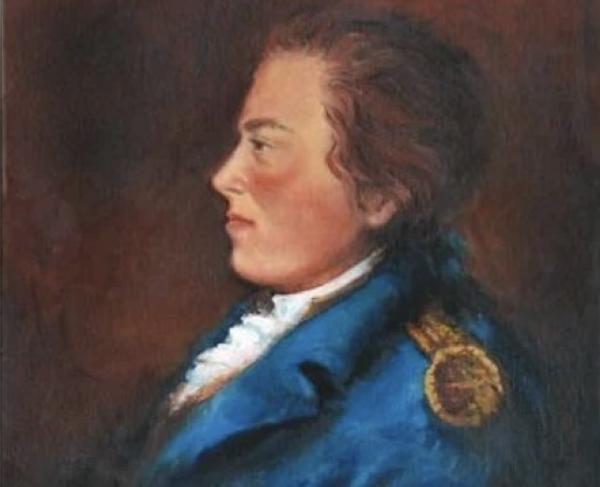

Richard Henry Lee

Although Richard Henry Lee demonstrated an unparalleled commitment to American independence, his name and work are not prevalent in U.S. public memory. Lee’s passionate and multifaceted opinions about the budding new nation were especially evident in his vehement defense of declaring independence from Great Britain.

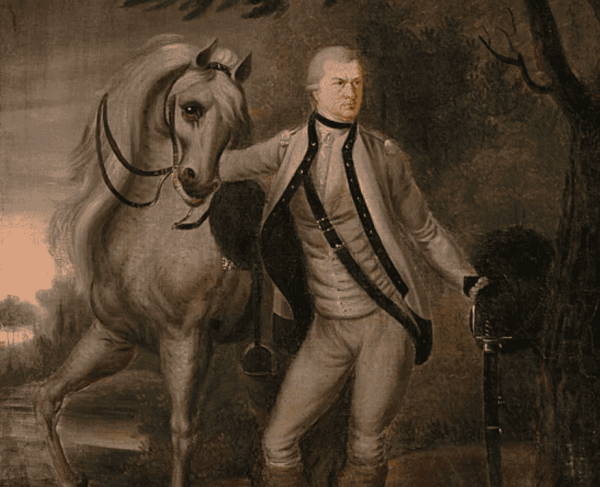

Lee was raised on a plantation along the Potomac River in Stratford, in northern Virginia. At 22 years old, Lee befriended Virginia militia officer George Washington, who had recently gained authority over the Mount Vernon estate. Lee’s political career took flight when one of George Washington’s brothers encouraged Lee to seek out his position as a delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses, and Lee joined his other extended family members who were already delegates. Together, the group created “the largest, most powerful voting bloc in the legislature” during the house session of 1757.

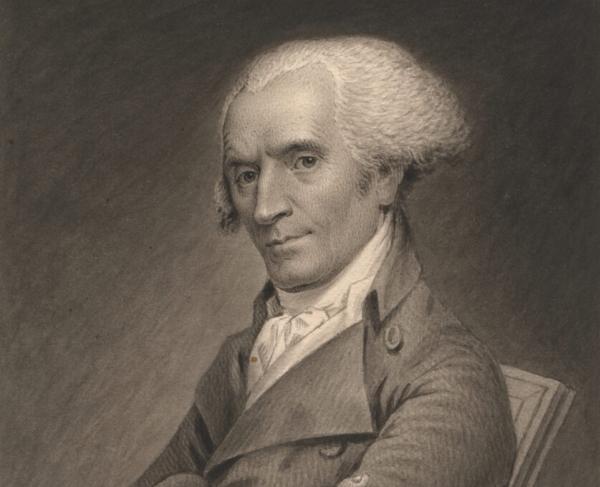

Like other patriots in the 1760s, British parliamentary actions infuriated Lee. He called Parliament “a most wicked system for destroying the liberty of America.” Notably, Lee had mixed reactions to British acts and laws enacted in the colonies. While he disapproved of things like the Tea Act, the Quebec Act especially angered Lee because of how it directly impeded his personal property claims. Despite his strong distaste for British policies, Lee looked poorly upon the aggressive protest tactics of Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty. For example, he did not condone the Boston Tea Party’s wreckage of personal effects. He also thought that the tea party would provoke the British, who may use “harsh measures” as retaliation. Lee regarded Samuel Adams as a paramount figure in the fight for independence but did not believe he had the diplomatic prowess to handle the conflict in an effective way. The Quartering Act ultimately provoked Lee to conjure up a plan for what would be the Continental Congress to discuss “securing constitutional rights of America against the systematic plan for their destruction.” To this end, Lee organized a Virginia convention where the attendees chose representatives for the September 5, 1774, First Continental Congress. At this meeting, Congress refused Lee’s radical suggestion to have colonies prepare militias.

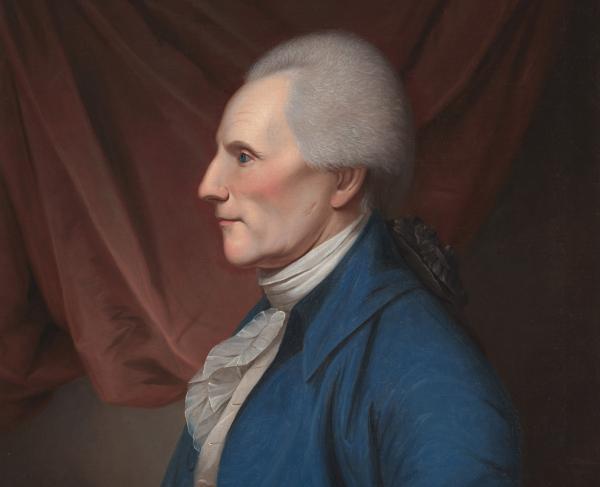

Despite this disapproval, Lee did not cease his efforts. After seeing continued British ships outside of New York, and hearing of a French plan to provide “necessities of any sort,” Lee once again encouraged the colonies to declare their independence and institute resolute state constitutions and governments. He said, “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be totally dissolved.” Lee’s thoughts took further convincing because the less developed colonies were too dependent on British security. John Adams and Richard Henry Lee propounded that Britain had already severed their alliances to the colonies when they went to war with them. In presenting this argument, Lee’s manner of speaking entranced the delegates— one Maryland delegate noted that “while you listened to him, you desired to hear nothing superior, and indeed through him perfect.” After this speech, Lee worked to convince the delegates to support his resolution. When the resolution passed, John Adams remarked to Abigail Adams that Lee would be known as the “Father of American Independence.” After his successful resolution, Lee abdicated responsibility in writing the official Declaration of Independence. Lee was appointed as chairman of the Articles of Confederation writing committee. Lee was the sixth person voted to be president under the Articles of Confederation. As his governmental career continued, Lee’s opinions conflicted with the values of the new U.S. Constitution. Lee staunchly opposed the new U.S. Constitution because of its preference to the oligarchy and the “danger that will ensure to civil liberty from the adoption of the new system in its present form.”

While Lee’s name may not be recognizable to those unfamiliar with the inner workings of early American government, his legacy is intrinsic, albeit anonymous, in the founding documents of the United States.

Further Reading:

First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call to Independence By: Harlow Giles Unger

“Richard Henry Lee: A Neglected Virginian Patriot and Statesman.” By: New York Tribune

“Richard Henry Lee” By: Biography.com