Appomattox Court House

Lee's Surrender

Appomattox County, VA | Apr 9, 1865

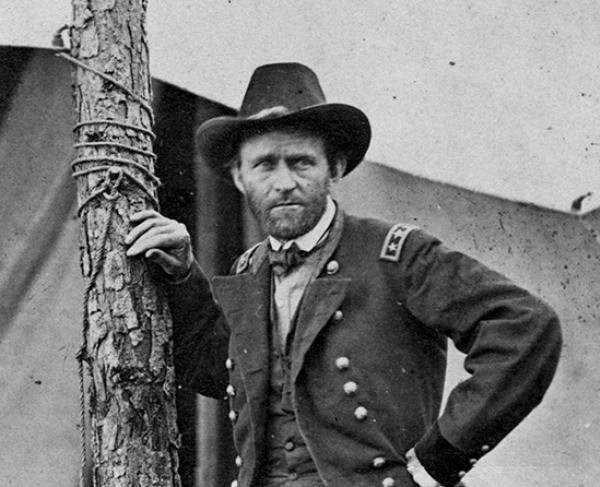

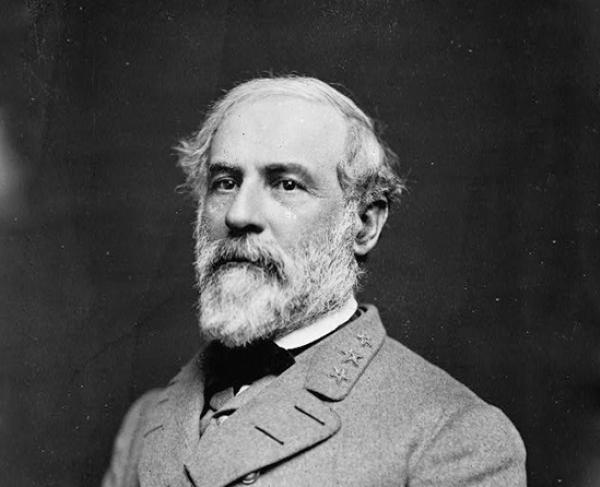

Trapped by the Federals near Appomattox Court House, Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Union general Ulysses S. Grant, precipitating the capitulation of other Confederate forces and leading to the end of the bloodiest conflict in American history.

How it ended

Union victory. Lee’s formal surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, brought the war in Virginia to an end. While this event is considered the most significant surrender of the Civil War, several other Confederate commanders had to capitulate and negotiate paroles and amnesty for Southern combatants before President Andrew Johnson could officially proclaim an end to the Civil War. That formal declaration occurred sixteen months after Appomattox, on August 20, 1866.

In context

General Lee's final campaign began on March 25, 1865, with a Confederate attack on Fort Stedman, near Petersburg. General Grant’s forces counterattacked a week later on April 1 at Five Forks, forcing Lee to abandon Richmond and Petersburg the following day. The Confederate Army’s retreat moved southwest along the Richmond & Danville Railroad. Heavily outnumbered by the enemy and low on supplies, Lee was in dire trouble. Nevertheless, he led a series of grueling night marches, hoping to reach supply trains in Farmville, Virginia, and eventually join Maj. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army in North Carolina. Union troops captured the valuable supplies at Farmville on April 7.

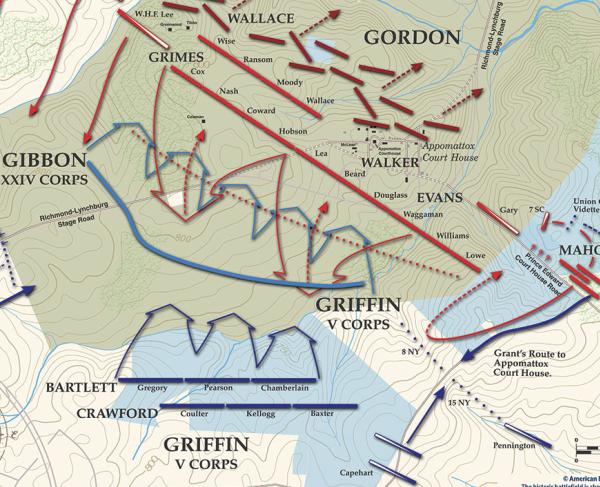

On April 8, the Confederates discovered that their army was blocked by Federal cavalry. Confederate commanders tried to break through the cavalry screen, hoping that the horsemen were unsupported by other troops. But Grant had anticipated Lee’s attempt to escape and ordered two corps (Twenty-fourth and Fifth), under the commands of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon and Bvt. Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin, to march all night to reinforce the Union cavalry and trap Lee. On April 9, those corps drove back the Confederates.

Rather than destroy his army and sacrifice the lives of his soldiers to no purpose, Lee decided to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia. Three days later, a formal ceremony marked the disbanding of Lee's army and the parole of his men, ending the war in Virginia. The Grant-Lee agreement served not only as a signal that the South had lost the war but also as a model for the rest of the surrenders that followed.

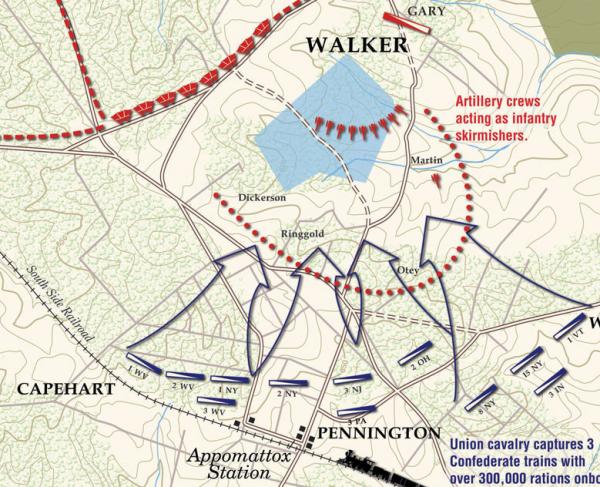

General Robert E. Lee heads west along the Appomattox River, eventually arriving in Appomattox County on April 8. His objective is the South Side Railroad at Appomattox Station, where critical food supplies have been sent up from Lynchburg. Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. George A. Custer reach them first, however, capturing and burning three supply trains.

Grant, aware that Lee's army was out of options, had written to Lee on April 7, requesting the Confederate general's surrender. But Lee still hopes to access more supplies further west at Lynchburg and does not capitulate. He does, however, ask what terms Grant is offering. The two generals continue their correspondence throughout the next day.

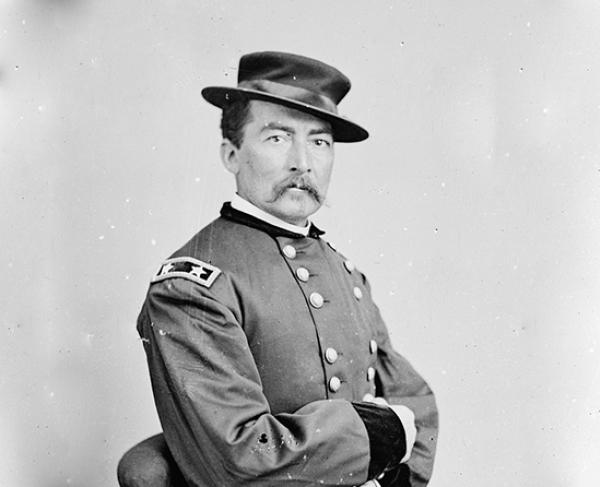

April 9. Approximately 9,000 Confederate troops under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon deploy in the fields west of the village before dawn and wait. Before 8:00 a.m., Maj. Gen. Bryan Grimes of North Carolina successfully launches an attack against Union calvary under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan. The outnumbered Union cavalry fall back, temporarily opening the road to the Confederates. But more Union infantry under Gibbon and Griffin begin arriving from the west and south, encircling Lee’s forces. Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Rebel troops are being pressed from the rear near New Hope Church, three miles to the east. General Ulysses S. Grant’s goal of cutting off and destroying Lee’s army is within reach.

Bowing to the inevitable, Lee orders his troops to retreat through the village and back across the Appomattox River. Small pockets of resistance continue to erupt until flags of truce are sent out from the Confederate lines between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m. Lee and Grant exchange messages and agree to meet at the Wilmer McLean home at Appomattox Court House that afternoon. There, Lee surrenders the Army of Northern Virginia.

152

500

The surrender of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia sets the stage for the conclusion of the Civil War. Through the lenient terms, Confederate troops are paroled and allowed to return to their homes while Union soldiers are ordered to refrain from overt celebration or taunting. These measures serve as a blueprint for the surrender of the remaining Confederate forces throughout the South.

Although a formal peace treaty is never signed by the combatants, the submission of the Confederate armies ends the war and begins the long and arduous road toward reunification of North and South.

According to Grant, who recorded the experience in his memoirs, the two generals treated one another with courtesy and respect. They initially attempted to break the ice by recalling their old army days during the Mexican American War. Grant was flattered that Lee remembered him from that time, as he was much younger than Lee and more junior in rank. Then, they got down to negotiating the terms of surrender. Despite being the victor, Grant felt no joy in Lee’s defeat.

What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassable face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.

Grant drafted the following generous terms of surrender, which avoided the harsh punishment and humiliation of Lee’s men.

Gen.: In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor.their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

The following day allowed a long-awaited emotional release for those who had once been fellow citizens, then armed foes for four years. Grant, accompanied by his staff and other officers, met with Lee once again. The Union general sensed that his men wanted to visit the Confederate lines and greet some of the men they had trained with before the war. Lee kindly consented:

They went over, had a very pleasant time with their old friends, and brought some of them back with them when they returned. . . . When Lee and I separated he went back to his lines and I returned to the house of Mr. McLean. Here the officers of both armies came in great numbers, and seemed to enjoy the meeting as much as though they had been friends separated for a long time while fighting battles under the same flag. For the time being it looked very much as if all thought of the war had escaped their minds.

It took several months after Appomattox for all the Confederate armies to capitulate, and still the war was not declared at an end until Texas formed a new state government that accepted the abolition of slavery in August 1866.

After Lee's surrender, the Army of Tennessee remained in the field for over two weeks, until Maj. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston finally surrendered to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on April 26. Johnston's surrender was the largest of the war, totaling almost 90,000 men. When news of Johnston’s surrender reached Alabama, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, the son of President Zachary Taylor and commander of some 10,000 Confederate men, surrendered his army to his Union counterpart on May 4. Several days later, Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest gave up his cavalry corps at Gainesville, Alabama, telling his men: “…further resistance on our part would justly be regarded as the very height of folly and rashness.”

The final battle of the Civil War took place at Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 11–12. The last large Confederate military force was surrendered on June 2 by Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith in Galveston, Texas. Yet Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, the first Native American to serve as a Confederate general, kept his troops in the field for nearly a month after Smith gave up the Trans-Mississippi Army. On June 23, Watie finally acknowledged defeat and surrendered his unit of Confederate Cherokee, Creek, Seminole and Osage troops at Doaksville, near Fort Towson (now Oklahoma), becoming the last Confederate general to give up his command.

The CSS Shenandoah, a former British trade ship repurposed as a Confederate raider, continued preying on Union commercial ships in the Bering Sea long after the rebellion ended on land. Only in August 1865, when its skipper, Lt. Cmdr. James Waddell, got word that the war had definitively ended, did the ship escape to Liverpool, England, and lower the Confederate flag.

By April 1866, one year after Appomattox, the insurrection was over in all of the former Confederate states but Texas, which had not yet succeeded in establishing a new state government. President Andrew Johnson eventually accepted Texas’s constitution—which grudgingly agreed to the abolition of slavery—and on August 20, 1866, proclaimed that “said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole United States of America.”

Appomattox Court House: Featured Resources

All battles of the Appomattox Campaign

Related Battles

63,285

26,000

152

500