Bull Run

First Manassas

Fairfax County and Prince William County, VA | Jul 21, 1861

Bull Run was the first full-scale battle of the Civil War. The fierce fight there forced both the North and South to face the sobering reality that the war would be long and bloody.

How it ended

Confederate victory. After this stinging defeat for the Union, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell, the commander of the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, was relieved and replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who set about reorganizing and training what would become the Army of the Potomac.

In context

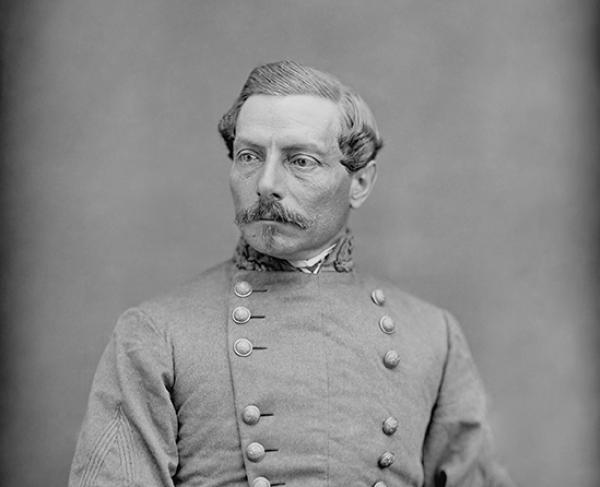

Although the Civil War officially began when Confederate troops shelled Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the fighting didn’t commence in earnest until the Battle of Bull Run, fought months later in Virginia, just 25 miles from Washington D.C. Under public pressure to end the war in 90 days, President Lincoln had pushed the cautious Gen. McDowell to embark on a campaign to capture the Confederate capital in Richmond, but McDowell’s troops were stopped at Bull Run by Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard’s Rebel forces. The Federals retreated to Washington, where the Lincoln administration retooled for a war that would be waged at great human and financial cost

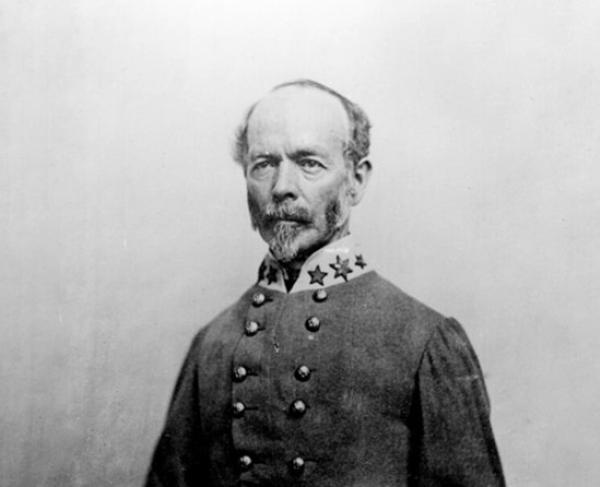

On July 16, the Union 90-day volunteer army under McDowell—around 35,000 troops with great enthusiasm and little training—sets out from Washington, D.C. The Confederates under Beauregard, equally green, are positioned behind Bull Run Creek west of Centreville. They aim to block the Union army advance on the Confederate capital by defending the railroad junction at Manassas, just west of the creek. The railroads there connect the strategically important Shenandoah Valley with the Virginia interior. Another Confederate army under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston operates in the Valley and is poised to reinforce Beauregard. McDowell’s plan is to make quick work of Beauregard’s force before Johnston can join him.

On July 17, both sides skirmish along Bull Run at Blackburn’s Ford near the center of Beauregard’s line. The inconclusive fight causes McDowell to revise his attack plan, which requires three more days to implement. Meanwhile, Johnston’s men in the Valley manage to elude the Federals and board trains headed for Bull Run. They arrive at the scene on July 20.

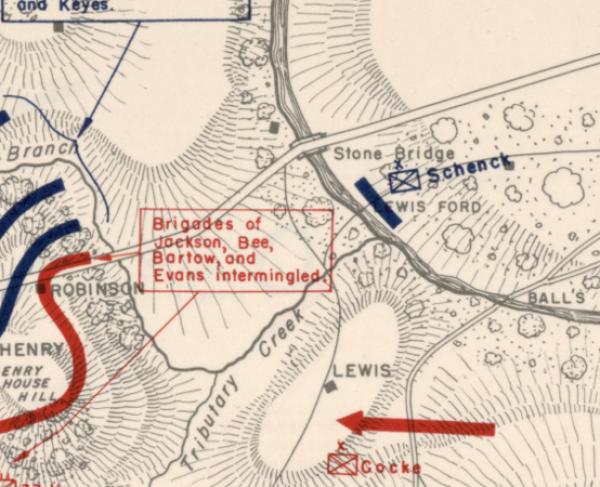

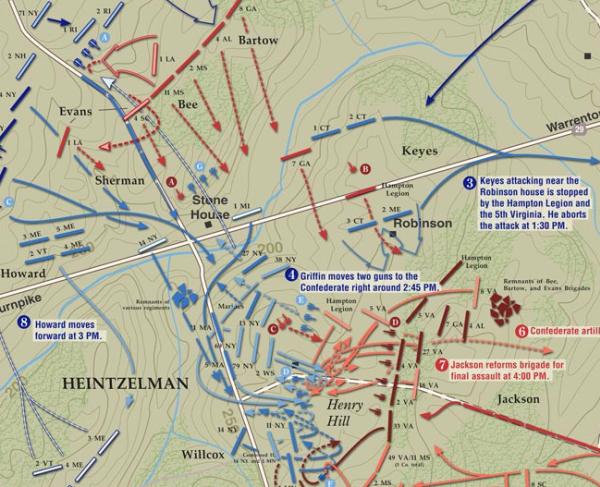

July 21. McDowell’s early morning advance up Bull Run Creek to cross behind Beauregard’s left is hampered by an ambitious plan that requires complex synchronization. Constant delays on the march by the green officers and their troops, as well as effective scouting by the Confederates, give McDowell’s movements away. Later that morning, McDowell’s artillery shells the Confederates across Bull Run near a stone bridge. Two divisions finally cross at Sudley Ford and make their way south behind the Confederate left flank. Beauregard sends three brigades to handle what he thinks is only a distraction, while planning his own flanking movement of the Union left.

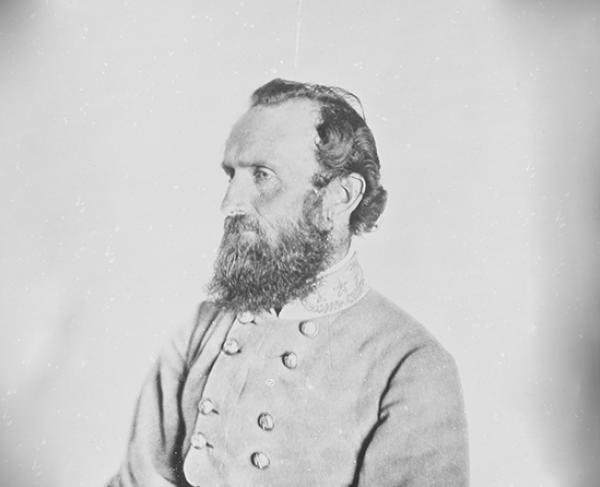

The Federals have the upper hand throughout the morning as they drive Confederate forces back from Matthews Hill. The retreating Confederates rally on an open hilltop near the home of the widow Judith Henry, where a brigade of Virginia regiments led by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson assembles. Jackson forms the scattered Confederate artillery into a formidable line on the eastern slope of the hill with his infantry hidden in the tall grass behind the guns.

As the Confederates reinforce their lines, McDowell pauses his attack. Consolidating his own forces, he moves more divisions across Bull Run and occupies Chinn Ridge, west of Henry Hill. Then McDowell blunders. He places two rifled artillery batteries on the western side of Henry Hill within 300 yards of Jackson’s guns. Union infantry regiments soon become targets of Jackson’s nearby artillery. A contest between infantry and artillery erupts, causing havoc and accidentally killing Judith Henry in the crossfire as she hides in her home.

Jackson’s men hold firm. Sometime during the fighting, Confederate Brig. Gen. Bernard Bee calls encourages his own brigade to rally with Jackson, who, he declares, is standing like a “stone wall.” Although he is killed in action, Bee's statement lives on, and from that moment Jackson is known as “Stonewall.”

Late in the afternoon, Confederate reinforcements under Col. Jubal Early extend the Confederate line and attack the Union right flank on Chinn Ridge. Jackson’s men advance across the top of Henry Hill and push back the Federal infantry, capturing some of the guns. The withdrawal of the Union center quickly spreads to the flanks. Virginia cavalry under Col. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart arrive on the field and charge into a confused mass of Union regiments. The Federals retreat.

2,896

1,982

As the battle ends, the Confederates are bolstered by the arrival from Richmond of President Jefferson Davis, but the victorious forces are too disorganized to pursue the Federals. McDowell’s fleeing forces, already hampered by narrow bridges and overturned wagons, are further impeded by hordes of fleeing civilian spectators, who had come down from Washington to enjoy the spectacle. By July 22, the remnants of the shattered Union army reach the safety of Washington, D.C. McDowell is later relieved of his command.

While there was a clash of “blue” and “gray” at Bull Run in the sense that the North met the South in battle, the distinction between the colors of the two armies was not easily discerned in the hail of minié balls and the haze of artillery smoke. Most soldiers were volunteers from cities and towns throughout the North and South and reported for duty in the uniforms of their local units. Some Confederates actually wore blue and some Federals were clad in gray. To complicate matters, exotically dressed Zouaves, an elite Union regiment, joined the fray in red trousers and fezes.

Colonel William T. Sherman commanded a brigade under McDowell at Bull Run. In a report issued to command after the battle, he recounted how confusion over uniforms resulted in disorder and panic that stifling day.

Before reaching the crest of this hill the roadway was worn deep enough to afford shelter, and I kept the several regiments in it as long as possible; but when the Wisconsin Second was abreast of the enemy, by order of Major Wadsworth, of General McDowell’s staff, I ordered it to leave the roadway by the left flank, and to attack the enemy. This regiment ascended to the brow of the hill steadily, received the severe fire of the enemy, returned it with spirit, and advanced delivering its fire. This regiment is uniformed in gray cloth, almost identical with that of the great bulk of the secession army, and when the regiment fell into confusion and retreated toward the road there was an universal cry that they were being fired on by our own men. The regiment rallied again, passed the brow of the hill a second time, but was again repulsed in disorder.

Later in the war, uniforms were standardized, with most Union troops wearing blue and most Confederate troops wearing gray. Still, there were problems. Regulation uniforms were sometimes in short supply and soldiers simply wore their own clothes. This led to further instances of friendly fire as the conflict endured.

Most of McDowell’s troops at Bull Run were 90-day volunteers, who responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s rallying call on April 13, 1861, the day after the attack on Fort Sumpter:

…I, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, President of the United States, in virtue of the power in me vested by the Constitution and the laws, have thought fit to call forth, and hereby do call forth, the militia of the several States of the Union, to the aggregate number of seventy-five thousand …. I appeal to all loyal citizens to favor, facilitate, and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government; and to redress wrongs already long enough endured.

Eager men streamed into Washington to defend the Union capital. Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter wrote to his son on April 19, “the Capitol itself is turned into a barracks; there will be 30,000 troops here by tomorrow night.” But these loyal Americans were citizens, not soldiers. Although some had training in local state militias, most had no battle experience and held romantic notions about the glory of war. Few has a sense of discipline and fewer had uniforms. This was the ragtag crew assigned to Irvin McDowell’s command in the summer of 1861.

After the defeat at Bull Run, it became clear that serving 90 days of military service was completely unrealistic. The terms of the first men to join were already expiring that July and the war would be long. Congress quickly passed legislation expanding the size of the army and extending the length of enlistment, and then set about reorganizing Union forces for the arduous fight ahead.

Bull Run: Featured Resources

All battles of the Manassas Campaign - July 1861

Related Battles

28,450

32,230

2,896

1,982