Kennesaw Mountain

Cobb County, GA | Jun 27, 1864

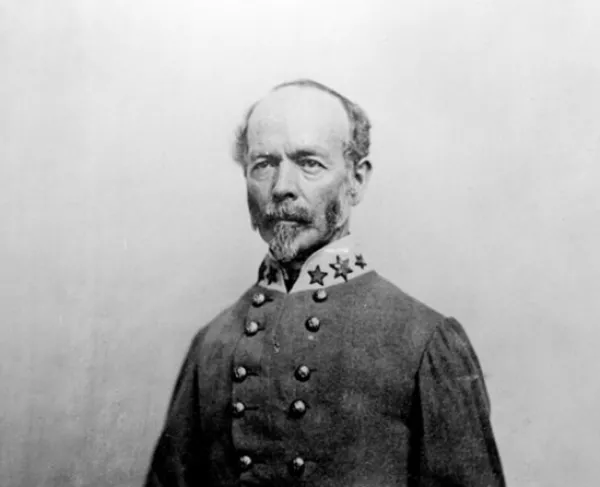

Mile by mile, William T. Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston slowly made their way toward Atlanta. Along the way, the armies clashed at New Hope Church, Pickett’s Mill, and Marietta. Johnston employed Fabian tactics as a means of slowing and stretching Sherman’s armies, withdrawing in the face of Sherman’s successive flanking maneuvers, while Sherman tried to avoid pitched battles that necessitated head-on assaults against fortified positions. This all changed at Kennesaw Mountain.

By June 19, Johnston’s main forced occupied a seven-mile-long defensive line. The position was well fortified, taking on a crescent-shaped battle formation, with the imposing Kennesaw Mountain rising more than 1,800 feet in elevation above Marietta, Georgia, and the surrounding terrain—and just 25 miles outside of Atlanta.

Fighting on June 22 at Kolb’s Farm convinced Sherman that Johnston’s line was overstretched. The Yankee commander formulated a plan of attack—a frontal attack—the first major frontal attack he ordered during the campaign. On June 24, Sherman issued attack orders that called for the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of the Cumberland to assault the Confederate right and center respectively. The Army of the Ohio would act as a diversion on the Confederate left. If all went well, Johnston’s army would be dispersed or destroyed, with the door to Atlanta swinging wide open. But it was not to be.

At 8 a.m. on June 27, more than fifty cannons roared to life on the Army of the Tennessee front. Troops of the Federal XV and XVII Corps skirmished in the dense undergrowth to prevent the Rebels from shifting forces to Little Kennesaw and Pigeon Hill. Three brigades of Maj. Gen. John Logan's XV Corps moved forward but, despite overrunning some of the rifle pits fronting them, could not penetrate the principal Confederate defenses. Most Federals became mired in the undergrowth and devastated by punishing musketry as they attempted to ascend the slope. Well-directed fire Confederate artillery fire on Little Kennesaw and a Confederate counterattack eventually drove off the Yankees.

At the center of the Union line, the opposing armies were only 400 yards apart. Portions of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s IV and Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer’s XIV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland entered the fray. Facing them was perhaps Johnston’s best division, that of Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne's, which had built nearly impregnable abatis and entrenchments along the divisional front. Brigadier General George Maney's Tennessee brigade held a position jutting forward in a salient on a rise now known as Cheatham's Hill. Federal artillery shelled the Rebel works for fifteen minutes before the infantry advanced, only to be stalled at the abatis around 50 yards short of the enemy works. Union Col. Daniel McCook, of the “Fighting McCook’s,” stood in front of the enemy parapet urging his men on when he was shot in the chest. On McCook's left, Brig. Gen. Charles Harker urged his men forward astride his white horse before being mortally struck in the arm and chest. By 10 a.m., the Union attack became disorganized, and the men fell back. Some men of Col. John Mitchell's brigade made it up the slope to Maney's entrenched salient, where the lines became so close that the Tennesseans threw rocks at the advancing Federals. Eventually, Mitchell's men retreated and found cover within yards of the Confederate works. Afterward, the combatants dubbed the area of the most brutal fighting the "Dead Angle."

By noon, the Union attack had failed. Although the survivors of the assaulting columns spent the next five days in advanced works just yards from the Confederate position, there was no more heavy fighting at Kennesaw. On July 2, Sherman maneuvered a force around Johnston’s left flank, forcing the Confederates to fall back once again closer to Atlanta.

Kennesaw Mountain: Featured Resources

All battles of the Atlanta Campaign

Related Battles

100,000

50,000

3,000

1,000