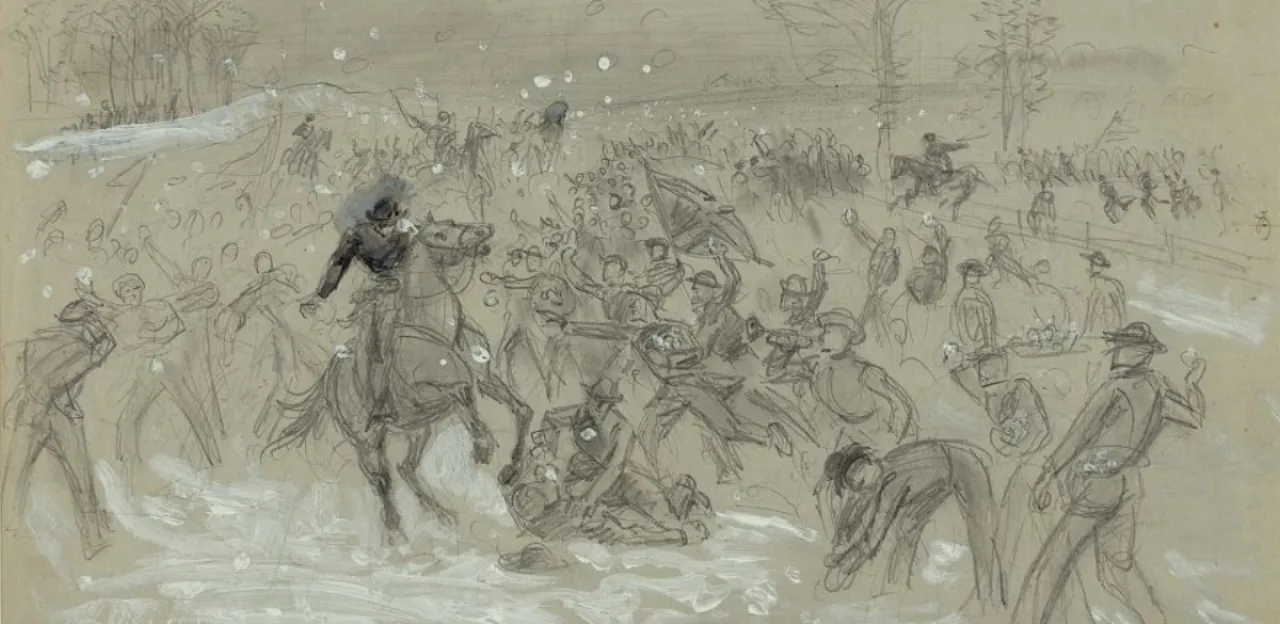

“A Desperate Snow Battle”

This excerpt from A History of Kershaw's Brigade, a memoir written by an officer in the 3rd South Carolina, describes a large-scale snowball fight which took place between Confederate soldiers in the winter of 1862-1863.

The troops delight in "snow balling," and revelled in the sport for days at a time. Many hard battles were fought, won, and lost; sometimes company against company, then regiment against regiment, and sometimes brigades would be pitted against rival brigades.

When the South Carolinians were against the Georgians, or the two Georgia brigades against Kershaw's and the Mississippi brigades, then the blows would fall fast and furious. The fiercest fight and the hardest run of my life was when Kershaw's Brigade, under Colonel Rutherford, of the Third, challenged and fought Cobb's Georgians.

Colonel Rutherford was a great lover of the sport, and wherever a contest was going on he would be sure to take a hand. On the day alluded to Colonel Rutherford martialed his men by the beating of drums and the bugle's blast; officers headed their companies, regiments formed, with flags flying, then when all was ready the troops were marched to the brow of a hill, or rather half way down the hill, and formed line of battle, there to await the coming of the Georgians. They were at that moment advancing across the plain that separated the two camps. The men built great pyramids of snow balls in their rear, and awaited the assault of the fast approaching enemy. Officers cheered the men and urged them to stand fast and uphold the "honor of their State," while the officers on the other side besought their men to sweep all before them off the field.

The men stood trembling with cold and emotion, and the officers with fear, for the officer who was luckless enough as to fall into the hands of a set of "snow revelers," found to his sorrow that his bed was not one of roses.

When the Georgians were within one hundred feet the order was given to "fire." Then shower after shower of the fleecy balls filled the air. Cheer after cheer went up from the assaulters and the assaultant—now pressed back by the flying balls, then to the assault again. Officers shouted to the men, and they answered with a "yell."

When some, more bold than the rest, ventured too near, he was caught and dragged through the lines, while his comrades made frantic efforts to rescue him. The poor prisoner, now safely behind the lines, his fate problematical, as down in the snow he was pulled, now on his face, next on his back, then swung round and round by his heels—all the while snow being pushed down his back or in his bosom, his eyes, ears, and hair thoroughly filled with the "beautiful snow."

After a fifteen minutes' struggle, our lines gave way. The fierce looks of a tall, muscular, wild-eyed Georgian, who stood directly in my front, seemed to have singled me out for sacrifice. The stampede began. I tried to lead the command in the rout by placing myself in the front of the boldest and stoutest squad in the ranks, all the while shouting to the men to "turn boys turn." But they continued to charge to the rear, and in the nearest cut to our camp, then a mile off, I saw the only chance to save myself from the clutches of that wild-eyed Georgian was in continual and rapid flight.

The idea of a boy seventeen years old, and never yet tipped the beam at one hundred, in the grasp of that monster, as he now began to look to me, gave me the horrors. One by one the men began to pass me, and while the distance between us and the camp grew less at each step, yet the distance between me and my pursuer grew less as we proceeded in our mad race. The broad expanse that lay between the men and camp was one flying, surging mass, while the earth, or rather the snow, all around was filled with men who had fallen or been overtaken, and now in the last throes of a desperate snow battle. I dared not look behind, but kept bravely on. My breath grew fast and thick, and the camp seemed a perfect mirage, now near at hand then far in the distance.

The men who had not yet fallen in the hands of the reckless Georgians had distanced me, and the only energy that kept me to the race was the hope that some mishap might befall the wild-eyed man in my rear, otherwise I was gone. No one would have the temerity to tackle the giant in his rage. But all things must come to an end, and my race ended by falling in my tent, more dead than alive, just as I felt the warm breath of my pursuer blowing on my neck. I heard, as I lay panting, the wild-eyed man say, "I would rather have caught that d——n little Captain than to have killed the biggest man in the Yankee Army."