Fort Ticonderoga (1775)

New York | May 10, 1775

The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery.

How it ended

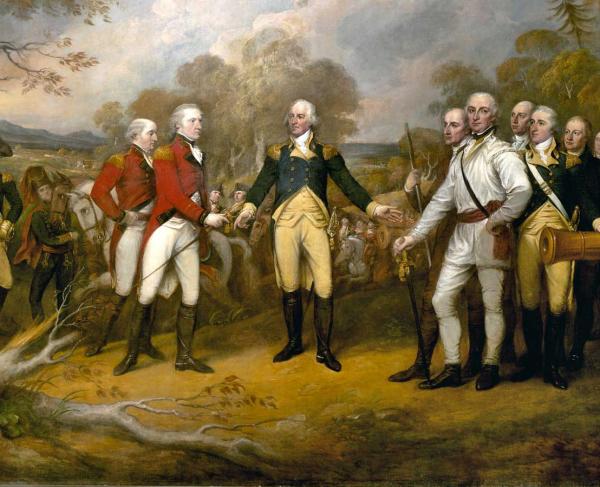

American victory. Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, together with Benedict Arnold, surprised and overtook a small British garrison at the fort, acquiring valuable weapons for the Continental Army. Arnold took command of Ticonderoga until he was relieved in June 1775.

In context

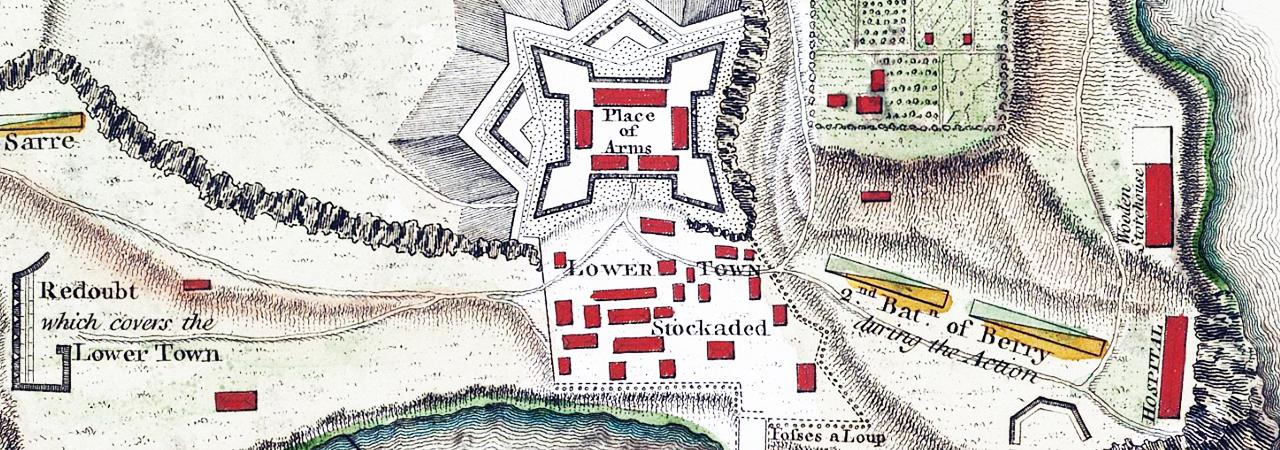

Located at the confluence of Lake Champlain and Lake George, Fort Ticonderoga controlled access north and south between Albany and Montreal. This made it a critical battlefield of the French and Indian War. Begun by the French as Fort Carillon in 1755, it was the launching point for the Marquis de Montcalm’s famous siege of Fort William Henry in 1757. The British attacked Montcalm’s French troops outside Fort Carillon on July 8, 1758, and the resulting battle was one of the largest of the war, and the bloodiest battle fought in North America until the Civil War. The fort was finally captured by the British in 1759.

During the American War for Independence, several engagements were fought at the five-pointed star-shaped Fort Ticonderoga. The most famous of these occurred on May 10, 1775, when Ethan Allen and his band of Green Mountain Boys, accompanied by Benedict Arnold, who held a commission from Massachusetts, silently rowed across Lake Champlain from present-day Vermont and stormed the fort in a swift, late-night sneak attack.

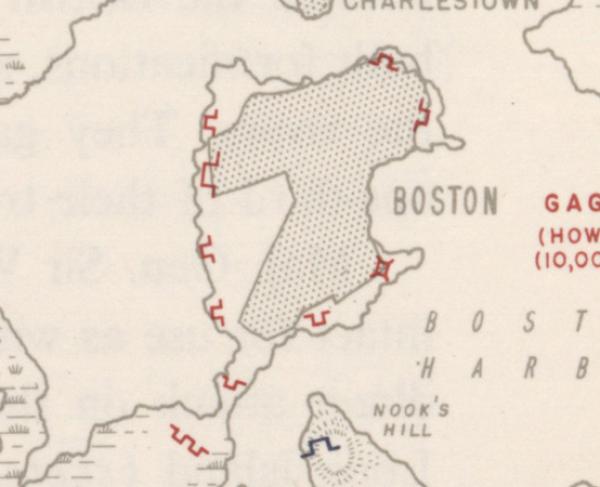

Months later, George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, sent one of his officers, Colonel Henry Knox, to gather the artillery left at Ticonderoga and bring it to Boston. Knox organized the transfer of the heavy guns over frozen rivers and the snow-covered Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts. Mounted on Dorchester Heights, the guns from Ticonderoga compelled the British to evacuate the city of Boston in March of 1776.

In 1775, Fort Ticonderoga is garrisoned by a small detachment of about 50 men and has fallen into disrepair, but its value—both for its location and the arms it houses—is well known. Patriot Benedict Arnold persuades the Massachusetts provisional government to give him a commission to command a secret mission to capture the fort. But Arnold soon learns that Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys are already on their way north toward Ticonderoga with the same intention. Arnold is warned that although Allen has no official sanction for his planned attack, his loyal men are unlikely to take orders from anyone else. Arnold feels that he should lead the expedition based on his formal authorization to act from the Massachusetts government. He and Allen come to an agreement about sharing command, despite the objections of some of Allen’s men. Ultimately, their force includes about 100 of Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and 50 other men recruited throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts.

By 11:30 p.m. on May 9, the men are ready to cross the lake from what is now Vermont to Ticonderoga. The small boats do not arrive until 1:30 a.m. and they cannot accommodate the entire force. Eighty-three of the Green Mountain Boys make the first crossing with Arnold and Allen. As dawn approaches, Allen and Arnold, worried about losing the element of surprise, decide to attack with the men at hand.

83

48

May 10. The lone sentry is quickly pushed aside. Allen, Arnold, and a few other men charge up the stairs toward the officers' quarters. When the British commander asks under whose authority he is acting, Allen allegedly replies, “In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress,” and demands the British surrender the fort.

Nobody is killed in the attack. Allen’s men plunder the premises for liquor and other provisions and celebrate their victory by getting drunk. Horrified by their behavior and fearful that they might damage or steal the lucrative armaments, Arnold insists order be restored, but he has little authority over the Green Mountain Boys. Allen and his men eventually leave. Arnold remains behind until he is relieved of command in June 1775, after 1,000 patriots from Connecticut arrive to reinforce the fort bringing with them a General who holds a commission from Congress. Taking umbrage, Arnold resigns his commission, beginning the long, sour story of his disgruntled relations with Congress and the hierarchy of the Continental Army.

1

48

The great prize for the American cause is not the fort itself, but rather the vast trove of artillery, which Henry Knox transports to Boston later that year. Fort Ticonderoga remains firmly in American hands until the Saratoga Campaign of 1777, when the British Army, under the command of General John Burgoyne, recaptures it as they move south from Canada towards Albany, New York. Seizing the unoccupied high ground of nearby Mount Defiance, Burgoyne’s engineers haul their cannons to the top of the mountain and aim them at Fort Ticonderoga. Seeing their plight, the American garrison abandons the fort without a fight on July 5, 1777. After Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga in October 1777, the fort no longer plays a major role in the war as the theater of British military operations moves south.

The Green Mountain Boys were a militia organization first established in 1770 in the territory between the British provinces of New York and New Hampshire known as the New Hampshire Grants. In the 1750s and 1760s, the New York and New Hampshire colonies issued competing land grants to settlers in the northwest frontier region, the area that later became Vermont. In 1764 King George III ruled that the area was part of New York, and the New York government planned to evict many Hampshire Grant settlers. However, the Hampshire Grant residents believed that even if New York owned the area, the colony had no right to evict them. They had built farms in the wilderness and felt they should not be forced to abandon them. These landholders maintained that their personal liberties were being violated, and they vowed to defend themselves.

In 1771 the settlers resolved to resist New York control with a militia named for the local topography. They formed the Green Mountain Boys and elected land speculator Ethan Allen as their colonel and commander. Allen and the Green Mountain Boys were tough frontiersmen and employed terror tactics such as threats, humiliation, and intimidation to chase off any who attempted to exert New York control over the area, including land surveyors, law officials, and settlers. When Americans rose up in rebellion against the British in 1775, the militia was also ready to take on the cause of independence.

The bravado of the Green Mountain Boys served them well at Fort Ticonderoga, where they took it upon themselves to capture the British garrison with no official commission from the Congress. But it failed in the summer of 1775, when Allen and his men, now part of the Continental Army, decided to seize Montreal, Canada, in a joint attack with about 200 Massachusetts militia. Allen had boasted, “with fifteen hundred men and a proper artillery, I will take Montreal.” But he attacked the city with only 100 men and no artillery against an army twice the size.

The Green Mountain Boys disbanded more than a year before Vermont declared its independence from Great Britain in 1777. The Vermont Republic operated for 14 years, before being admitted in 1791 to the United States as the fourteenth state. The remnants of the Green Mountain Boys militia were largely reconstituted as the Green Mountain Continental Rangers. Command of the newly formed regiment passed from Ethan Allen to Seth Warner. Allen joined the staff of Major General Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Army of New York, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. His regiment fought at the battles of Hubbardton and Bennington in 1777 before disbanding in 1779.

Vermont regiments called the Green Mountain Boys mustered again during the War of 1812, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and the Vietnam War, the Afghanistan War, and the Iraq War. Today it is the nickname of the Vermont National Guard.

To transport the heavy artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in winter, the resourceful Colonel Henry Knox put together a complex operation that included mobilizing a large corps of men, assembling a flotilla of flat-bottomed boats for the lake trip, building 40 special sleds, and gathering 80 yoke of oxen to pull the 5400-pound sleds. Although George Washington agreed to the ambitious and risky plan, his advisors had their doubts. The guns would have to be dismantled and loaded onto barges, transported down Lake George before the 30-mile-long lake froze, then hauled the rest of the way by sledge and oxen over rough trails.

Undaunted, Knox arrived at Fort Ticonderoga in early December 1775 and began disassembling the guns — 43 heavy brass and iron cannon, six cohorns, eight mortars, and two howitzers. They were removed from their mountings and transported by boat and ox cart to the head of Lake George. By December 9, all 59 guns were loaded onto flat-bottomed boats and headed down the lake. With a gale whipping up, Knox succeeded in getting the last of the cannon to the southern end of the lake just as it began to freeze over.

On December 17, Knox wrote to Washington, "I have had made forty two exceedingly strong sleds & have provided eighty yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield where I shall get fresh cattle to carry them to camp. . . . I hope in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery." But there was no snow, and the sleds could not be pulled on bare ground. Knox finally got his wish on Christmas. With several feet of fresh snow underfoot, he and his men cut a path toward Boston.

By January 5, the artillery had reached Albany, but the ice on the Hudson was not deep enough to support the weight of the sleds. During each of the first two attempts at crossing, Knox lost a precious cannon to the river. Finally, on the evening of January 8, he was able to write in his diary, "Went on the ice about 8 o'clock in the morning & proceeded so carefully that before night we got over 23 sleds & were so lucky as to get the Cannon out of the River, owing to the assistance the good people of the City of Albany gave." Powered by 80 yoke of oxen, Knox's "noble train of artillery" finally entered Cambridge on January 24, 1776.

Six weeks later, Washington's gun batteries in Cambridge distracted British troops while several thousand Americans quietly maneuvered the artillery up Dorchester Heights and frantically constructed emplacements. When British General Howe looked up at Dorchester Heights the next morning, he was dumbfounded: "The rebels did more in one night than my whole army would have done in one month." Thanks to Henry Knox’s efforts, British troops began to evacuate Boston on March 17.

Fort Ticonderoga (1775): Featured Resources

All battles of the Canadian Campaign

Related Battles

83

48

1

48