Yorktown

Siege of Yorktown

Virginia | Sep 28 - Oct 19, 1781

The Battle of Yorktown proved to be the decisive engagement of the American Revolution. The British surrender forecast the end of British rule in the colonies and the birth of a new nation—the United States of America.

How it ended

American victory. Outnumbered and outfought during a three-week siege in which they sustained great losses, British troops surrendered to the Continental Army and their French allies. This last major land battle of the American Revolution led to negotiations for peace with the British and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

In context

After six years of war, both the British and Continental armies were exhausted. The British, in hostile territory, held only a few coastal areas in America. On the other side of the Atlantic, Britain was also waging a global war with France and Spain. The American conflict was unpopular and divisive, and there was no end in sight. For the colonies, the long struggle for independence was leading to enormous debt, food shortages, and a lack of morale among the soldiers. Both sides were desperately seeking a definitive victory.

General George Washington and his Continental Army had a decision to make in the spring of 1781. They could strike a decisive blow to the British in New York City or aim for the south, in Yorktown, Virginia, where Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis’s troops were garrisoned. Washington and his French ally, Lt. Gen. Comte de Rochambeau, bet on the south, where they were assured critical naval support from a French fleet commanded by Adm. Comte de Grasse. The Allied armies marched hundreds of miles from their headquarters north of New York City to Yorktown, making theirs the largest troop movement of the American Revolution. They surprised the British in a siege that turned the tide toward an American victory in the War for Independence.

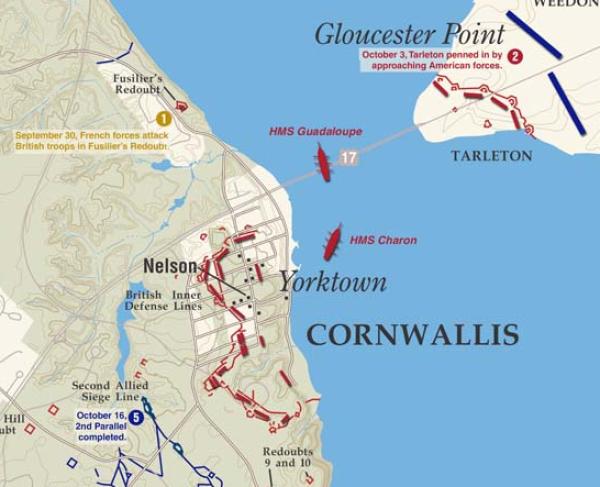

In the fall of 1781, the British occupy Yorktown, where Cornwallis intends to refit and resupply his 9,000-man army. While he awaits supplies and much-needed reinforcements from the Royal Navy, the Continental Army seizes an opportunity. On receiving word that the French fleet will be available for a siege south of New Jersey, Washington and Rochambeau move their force of almost 8,000 men south to Virginia, planning to join and lead about 12,000 other militia, French troops, and Continental troops in a siege of Yorktown.

On September 5, while the Allied army is still on route, the French fleet guards the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay. The Royal Navy, attempting to sail up the Bay to Cornwallis, is met by French warships at the mouth of the Chesapeake. In this encounter, called the Battle of the Capes, the British fleet is soundly defeated and forced to abandon Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown.

19,900

9,000

September 28. After a grueling march, the American and French forces arrive near Yorktown and immediately begin the hard work of laying siege to Cornwallis and his men. Cornwallis has thrown up a series of redoubts on the outskirts of Yorktown while the majority of his men hunker down in the town.

With the help of French engineers, American and French troops begin to dig a series of parallel trenches, which bring troops and artillery close enough to inflict damage on the British. Feverishly working night and day, soldiers of the combined forces employ spades and axes to create a perimeter line of trenches that will trap the British. As the work on the parallels continues, the British attempt to disrupt Allied operations by using what little artillery they have left. Their attempts prove futile.

October 9. The Allied lines are now within musket range of the British and American and French artillery are in place. In the afternoon, the Allied barrage begins, with the French opening the salvo. On the American side, George Washington touches off the first cannon to commence their assault. His artillery consists of three 24-pounders, three 18-pounders, two 8-inch (203 mm) howitzers, and 6 mortars, totaling 14 guns. For nearly a week the artillery barrage is ceaseless, shattering whatever nerve the British have remaining and punching holes in British defenses.

October 11. Washington orders troops to dig a second parallel 400 yards closer to the British lines. British redoubts #9 and #10 prevent the second parallel from extending to the river and the British are still able to reinforce the garrisons inside the redoubts. They have to be taken by force. The new line is in place by the morning of October 12.

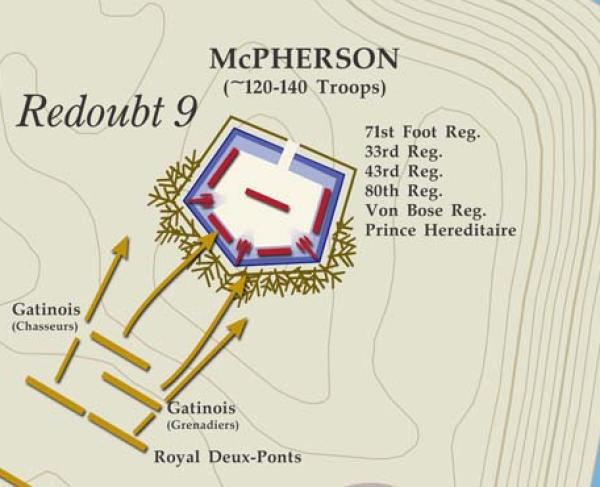

October 14. On a moonless night, after firing incessant artillery to weaken British defenses, American and French forces prepare a surprise assault on redoubts #9 and #10. To maintain stealth, soldiers do not to load or prime their weapons. The password for the operation is “Rochambeau,” which the Americans translate as “Rush on boys!” The assault commences with a diversionary attack on a redoubt further to the north of Yorktown at 6:30 p.m., giving the appearance that the town itself was to be stormed. Then, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton’s force, consisting of a detachment of 400 of his light infantry, assaults redoubt #10 with bayonets fixed and muskets unloaded. To prevent the British defenders from escaping the coming onslaught, Lt. Col. John Laurens’s troops cover the rear of the redoubt.

As American troops hack at the abatis with axes, the British are alerted. A British sentry fires at the Americans and the Americans proceeded to assault the fortification, climbing over the parapet and descending into the redoubt. Serious fighting ensues in close quarters, but the British are overwhelmed. It is a stunning victory with the Americans sustaining only 34 casualties.

The French simultaneously assault redoubt #9 and, after an equally fierce firefight, wrest control from the British. Cornwallis’s position is untenable as the Franco-American alliance has artillery on three of his sides, with additional new pieces positioned in redoubts #9 and #10 after their fall. In a last-ditch effort, Cornwallis orders a futile counterattack on October 15, which fails miserably.

October 17. That morning, a lone British drummer boy, beating “parley” and British officer waving a white handkerchief tied to the end of a sword are seen on a parapet at the forward position of the British lines. Blindfolded and brought inside American lines, the British officer secures terms of surrender for the British Army.

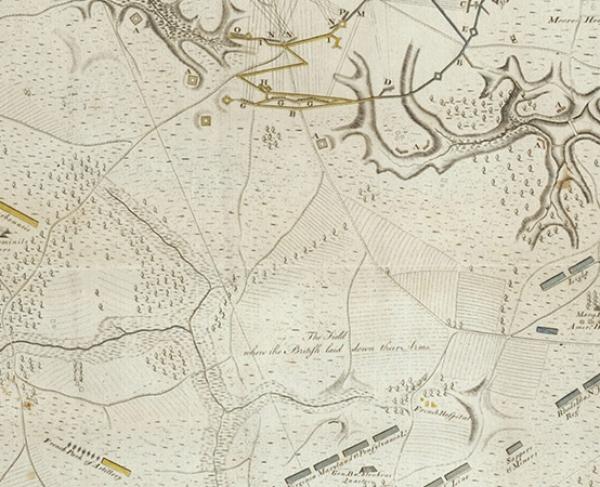

October 19. In a field outside of Yorktown, the capitulation takes place as British troops and their Hessian allies, with flags furled and cased, march sullenly between contingents of American and French forces. The British seek honorable terms of surrender, but Washington refuses as American forces were denied the that honor in Charleston, South Carolina, earlier in the war.

389

8,589

The Battle of Yorktown marks the collapse of the British war efforts. Later, it is said that the British band played the tune “The World’s Turned Upside Down” during the surrender at Yorktown—an apocryphal story that has become part of American folklore. But the world truly changes that day as the military operations of the War for Independence cease.

When news of Cornwallis’s surrender reaches London on November 25, the Prime Minister, Lord North, declares, “Oh God. It is all over. It is all over.” On March 5, 1782, Parliament passes a bill authorizing the government to make peace with America. Lord North resigns 15 days later. Although it takes the Americans two more years of skillful diplomacy to formally secure their independence through the Treaty of Paris, the war is won with the British defeat at Yorktown.

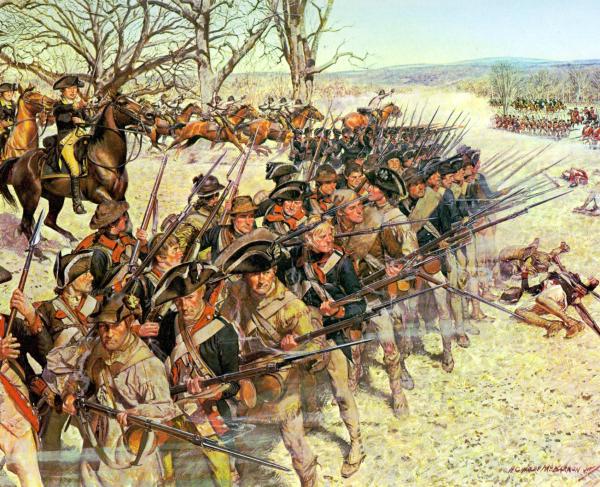

During the American Revolution, the colonies were facing a superpower. At that time, Britain possessed one of the best armies in the world. Their forces were well-equipped and expertly trained. The Continental Army, on the other hand, drew men of diverse ages and backgrounds into an undisciplined force. With few resources at hand, the Americans knew they would need to engage an ally if they were to sustain a fight for independence. France was a longtime foe of Britain and still thirsting for revenge after their defeat by the Crown in the Seven Years War. In 1777, a delegation headed by Benjamin Franklin arrived at the court of Louis XVI to negotiate an alliance between the United States and France. The mission was a success, with the King agreeing to send muskets, mortars, gunpowder, and cash to America.

In 1779, despite Louis’ support, the Continental Army, was still struggling. The war with Britain had reached a stalemate. This time, France obliged requests for assistance by sending over some of its elite troops to help Washington’s patriots. The French commander was a respected officer named Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau. The 450 officers and 5,300 men of Rochambeau’s Expeditionary Forces landed off the coast of Rhode Island in July 1780. They marched for days to meet up with Gen. Washington’s troops in New York, where they were to attack the British stronghold in New York City. But plans changed. With the mission refocused on taking Cornwallis’s army in Yorktown, the French continued their trek for 300 miles and five weeks and helped win a critical victory for the Americans.

We don’t know. The legend about the British singing a popular tune called “The World Turned Upside Down” originated 30 years after the war in Alexander Garden’s Anecdotes of the American Revolution 2nd series (Charleston, 1828), p. 18. “The British Army marched out with colours cased, and drums beating a British or a German march. The march they chose was ‘The World Turned Upside Down.’” The anecdote was told second hand by a Maj. William Jackson of Philadelphia, who claimed to have received the information from Lt. Col. John Laurens. But historians have said it cannot be true. At that time, musicians played in the regiment in which they enlisted, not in a large massed band. In addition, there was no widely known tune at that time called “The World Turned Upside Down.” Finally, Article III of the “Articles of Capitulation” signed at Yorktown clearly states that “The [British] garrison…will march out…with shouldered arms, colours cased, and drums beating a British or German march. Ebenezer Denny, an American soldier who witnessed the event, noted in his journal the low British morale, as their “drums beat as if they did not care how.” Denny does not note any singing.

Still, “The World Turned Upside Down” creates the perfect ending to an event that changed the nation and the world. It is so dramatic, in fact, that playwright and composer Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote his own version of the fictional tune to cap the Battle of Yorktown scene in his Broadway hit Hamilton.

Yorktown: Featured Resources

All battles of the Yorktown Campaign

Related Battles

19,900

9,000

389

8,589