Fort McHenry

Maryland | Sep 13, 1814

The failed bombardment of Fort McHenry forced the British to abandon their land assault on the crucial port city of Baltimore. This British defeat was a turning point in the War of 1812, leading both sides to reach a peace agreement later that year.

How it ended

United States victory. American forces resisted the dramatic British bombardment of Fort McHenry and proved they could stand up to a great world power. The exploding shells and rocket fire from British warships inspired Francis Scott Key to pen the lyrics to the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Seeing no way to penetrate American defenses, the British withdrew their troops and gave up their Chesapeake Campaign.

In context

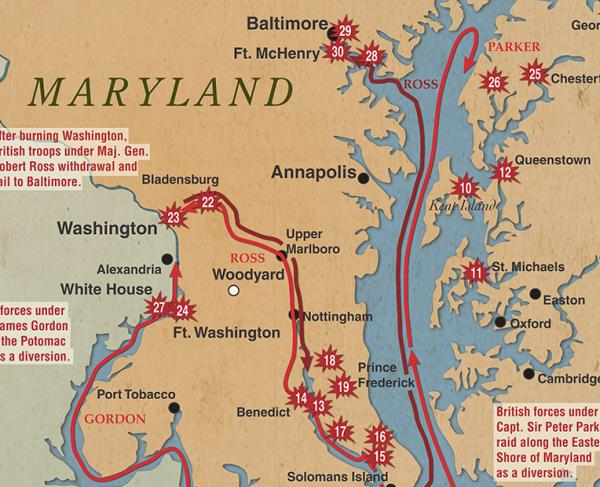

Initially, the British strategy during the War of 1812 had been defensive. The British were more concerned with defeating Napoleon in Europe than fighting a minor war with the United States. This changed on April 6, 1814, with the defeat and abdication of Napoleon, which freed up veteran troops for a more aggressive strategy. Major General Robert Ross was sent to command all British forces on the East Coast of the United States, with Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane leading a fleet of warships.

Encouraged by their victory at Bladensburg on August 24, 1814, and the subsequent burning of Washington, D.C., the British turned north, intent on capturing the major port city of Baltimore, Maryland. Militarily, Baltimore was a far more important city than Washington because of its thriving port and strategic location. The British hoped the loss of both Washington and Baltimore would cripple the American war effort and force peace. However, the citizens and militia of Baltimore had been preparing for such an assault for more than a year. The imposing Fort McHenry, at the mouth of the inner harbor, provided the linchpin for the American defenses.

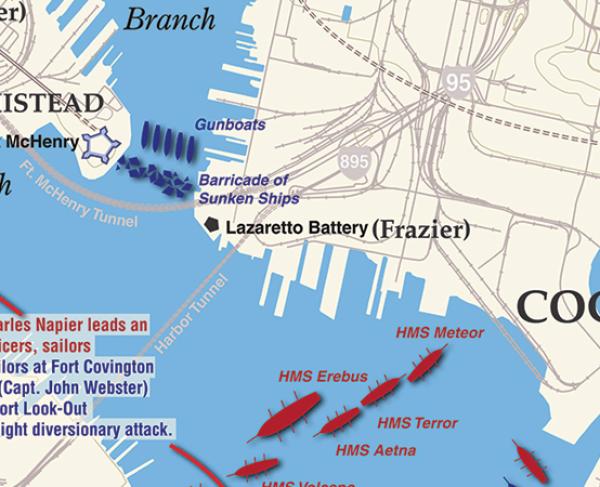

Fort McHenry, a large star fortress built in 1800, guards Baltimore’s inner harbor at a bend in the Patapsco River. The British plan to land troops on the eastern side of the city while the navy reduces the fort, allowing for naval support of the ground troops when they attack the city’s defenders.

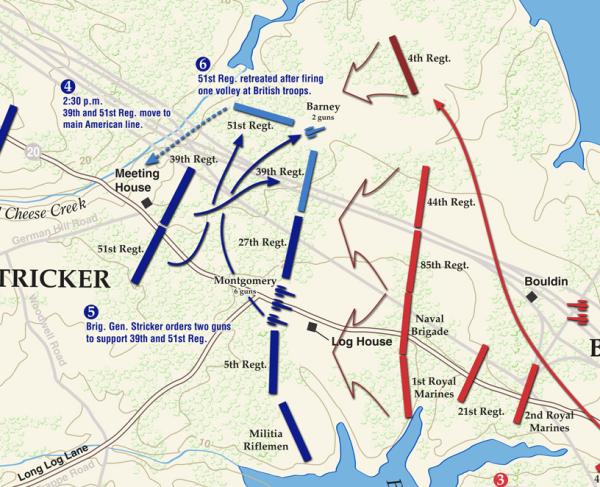

The British land a combined force of soldiers, sailors, and Royal Marines at North Point, a peninsula at the fork of the Patapsco River and Chesapeake Bay, on September 12, 1814. After landing unopposed, they advance toward Baltimore. The Maryland militia commander, Maj. Gen. Samuel Smith, orders Brig. Gen. John Stricker to delay the advance by provoking an engagement.

Around midday, while the British halt for a meal, Stricker orders 250 riflemen and cannon to draw the British toward his forces. Ross, hearing the skirmishing, rides forward to assess the situation. While ordering his men to drive off the American riflemen, Ross is shot in the chest and dies a few hours later. Command of the land forces passes to Col. Arthur Brooke.

Brooke collects the main body of the British troops and presses forward. Around 3:00 p.m., he attacks the American positions. The American defenders hold initially, inflicting heavy casualties and resorting to firing scrap metal from their cannon because of a lack of canister. Despite a stalwart initial defense, the Americans begin to give way to the British regulars. The Americans withdraw to Baltimore and Brooke halts for the rest of the day to consolidate his forces. This delay gives the American defenders in Baltimore time to bolster their defenses.

1,000

5,000

September 13. The Americans assemble 10,000 men and 100 cannon astride the Philadelphia Road, blocking the British advance toward Baltimore. This is a far stronger defense than the British expect; they are outnumbered two to one. Naval support will be required to dislodge the American forces, and Fort McHenry will have to be eliminated.

The 1,000 Americans at Fort McHenry are commanded by Maj. George Armistead. In the early morning of September 13, British warships begin their bombardment. Because of the shallow water, Admiral Cochrane is unable to use his heavy warships, and instead attacks with the bomb vessels HMS Terror, Volcano, Meteor, Devastation, and Aetna. These ships fire exploding mortar shells at high angles into the fort. Joining them is the rocket ship HMS Erebus, which launches the newly invented Congreve rockets. The ammunition used by these ships later inspire Francis Scott Key’s famous lines “and the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air.”

Initially the British fleet exchanges fire with the fort’s cannon, but soon withdraw out of range. For the next 27 hours, in driving rain, the warships hammer the fort. More than 1,500 cannonballs, shells, and rockets are fired, but only inflict light damage thanks to fortification efforts completed before the battle. During the night, Cochrane orders a landing party to slip past the fort and attempt to draw troops from the force opposing Brooke, but other than diverting some fire from the fort, this proves unsuccessful.

September 14. That morning the American defenders lower their battered storm flag and raise the large, 30 by 42-foot garrison flag that Major Armistead ordered a year earlier from local flag maker Mary Pickersgill. The garrison flag is raised every morning at reveille, but on this day—September 14, 1814—its presence has special significance.

28

1

The failed bombardment of Fort McHenry forces Brooke to abandon the land assault on Baltimore. The British set sail for New Orleans.

American Lawyer Francis Scott Key, held on a British warship for a prisoner negotiation during the frightening siege, feared that the fort had succumbed to the bombardment. But when he sees the large flag flying over the fort on the morning of September 14, he knows the fort held. The relief and awe he feels inspire him to write a poem, "Defense of Fort McHenry," which is later be set to the tune “To Anacreon in Heaven.” Renamed "The Star-Spangled Banner," the song officially becomes the national anthem of the United States in 1931.

The United States declared war on Britain in June 1812 to protect “free trade and sailors’ rights.” Heading into a conflict against a country with such superior naval power was a daunting prospect for the young nation. The government, therefore, turned to the many merchants and private sailors inhabiting its ports, issuing licenses to those who wished to gain financially from capturing enemy vessels. The privateers were armed, and their work was legally sanctioned. Although other East Coast ports were used by privateers, Baltimore was an especially busy haven for these sailors, who were paid generously for their work. Baltimore privateers were responsible for as much as one-third of all captured British vessels during the war. The harbor’s 122 American privateering vessels would ultimately cause some 16 million dollars of damage to the enemy.

The British hated the privateers and so despised the Baltimore that they called it a “nest of pirates.” They vowed to take revenge. Military personnel and residents of Baltimore were well aware that they were a target of enemy wrath and started shoring up their defenses. Among the preparations were upgrades of Fort McHenry, a 32-pound cannon battery along the water’s edge, fortifications at Lazaretto Point, and additional batteries arrayed along the banks of the Patapsco. Barges were stretched across the watery approaches creating choke points, and channels were left open to lure the British ships into kill zones. Volunteers dug huge entrenchments east of town, and the city militia drilled regularly. On land, defensive positions were established along North Point to prevent British troops from advancing. Thanks to these early and exhaustive plans, the British were repulsed at Fort McHenry in 1814 and abandoned their Chesapeake Campaign.

The flag we all know as the “star-spangled banner” is a massive 30 by 42 feet in size and sewn of wool bunting. Each of its 15 stars measures about two feet across and each of its 15 stripes are about two feet wide. Major Armistead commissioned Baltimore flag maker Mary Pickersgill to craft this dramatic emblem for his garrison as he was making preparations for Fort McHenry’s defense. He wanted to be sure the British could see the United States colors from their distant warships. Most people assume that this grand banner flew through “the rockets’ red glare.”

Or, maybe it was another flag. Some historians believe that a smaller, 17 by 25-foot storm flag may have flown over Fort McHenry during the rainy evening of the bombardment. Using a storm flag in those conditions would have been standard practice. The “star-spangled banner” may not have been run up the flagpole until first light on September 14.

We have Francis Scott Key to thank for the mix-up. Key, a 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet was detained on the British ship Tonnant off the cost of Baltimore when the bombardment began. He had successfully negotiated with the British for the release of an American prisoner but was held onboard because an assault was imminent. As the sloop tossed in violent waves, Key could only see the “red glare” of the enemy’s rockets and the sound of “bombs bursting in air.” He thought it unlikely that the Americans could hold out against such a volley of gunfire.

It was with huge surprise and joy that as dawn broke, he saw, not the Union Jack flying above the fort, but the American flag. But the inspiring banner he glimpsed may only have been raised at daylight. It may not have weathered “the perilous fight” as many believe.

Key started composing a verse about his experience while still onboard the Tonnant, and once he was safely rowed ashore, he edited the work into four stanzas. The final poem, called “The Defense of Fort M’Henry,” was printed and later set to the tune of a popular song. It was eventually retitled “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The composition was sung at patriotic gatherings and political events for more than a century before President Herbert Hoover proclaimed it the national anthem of the United States in 1931. But not everyone was a fan. The New York Herald Tribune wrote that the song had “words that nobody can remember to a tune nobody can sing.”

Fort McHenry: Featured Resources

All battles of the Chesapeake Campaign

Est. Casualties: 29

United States: 28

United Kingdom: 1

Related Battles

1,000

5,000

28

1