One of the first Black regiments to be mustered into the Union army during the American Civil War, the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry recruited many formerly enslaved Gullah Geechee men. Through a challenging beginning and later a unit name change—33rd United States Colored Troops—this regiment served bravely and often helped to bring freedom to plantation regions.

Union General David Hunter transferred to the Department of South which included federally-held coastal regions in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. Many of the sea island were cotton plantations, and on April 13, 1862, Hunter issued a proclamation that all “held to involuntary service by enemies of the United States…are hereby confiscated and declared to be free.” The proclamation sent ripples through the northern government and was months ahead of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation had mixed reactions among the enslaved population in the department; some left the plantations and sought freedom within Union lines, but many others feared they would be captured and sold to Cuba and ran away to the dense swamps and woods.

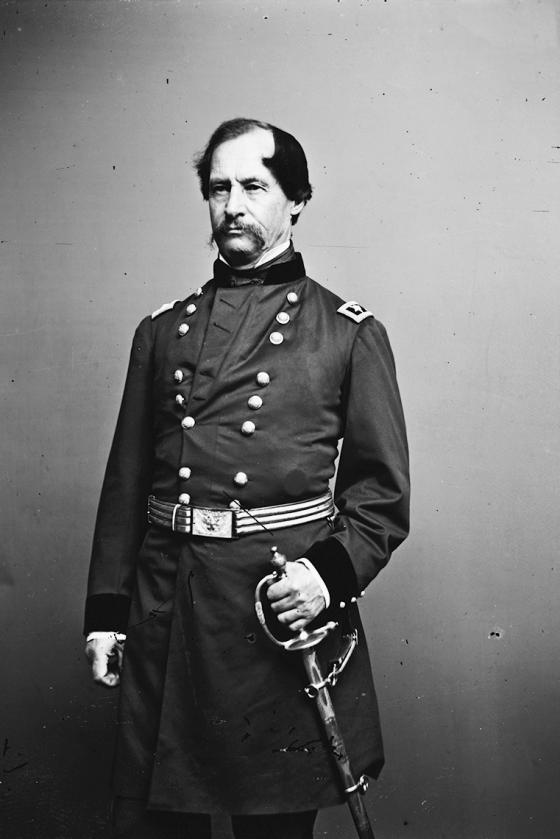

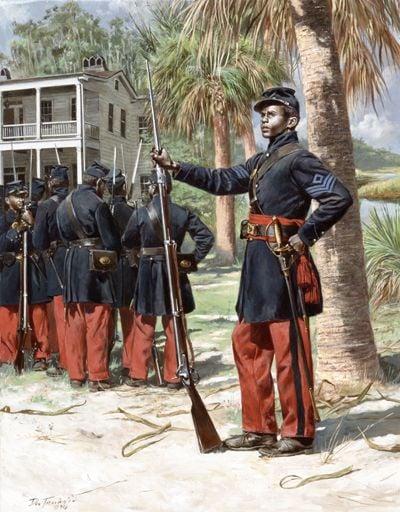

Eager to enlisted former enslaved men into the Union army, General Hunter went further in his department. He began to recruit and form a regiment of Black soldiers. Working with a minister named Abram Murchison, Hunter organized the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Regiment. However, the process of recruiting was not always understood or clear to the Black men joining the ranks. Some men complained that they were taken from the plantation fields and to the Union camps, without understanding what was happening or given a choice. The regiment organized at Hilton Head, South Carolina. The men were given blue coats and red pants for their uniforms and started learning military drill. The unit did not receive weapons at this time, and white officers anticipated the recruits would mostly perform manual labor for the Quartermaster Department.

News of General Hunter’s proclamation and new regiment was not welcome to many politicians in the north. Lincoln’s administration halted the proclamation but did not order the regiment to disband, though no official recognition was given and no pay was authorized for the Black soldiers. Hunter pushed back on criticism. However, by August 1862, so many soldiers had deserted from the 1st South Carolina—mostly because of the lack of pay—that Hunter disbanded the regiment, only keeping one company and assigning the soldiers to guard duty on St. Simon’s Island.

Within a few weeks, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton gave permission to “arm, equip, and receive into the service of the United States such volunteers of African descent as you may deem expedient, not exceeding 5,000.” Stanton classified the new recruiting effort under the Confiscation Act of 1862 which allowed slaves to be taken from plantations and employed as “contraband of war” with the Union army. Using this allowance, formerly enslaved men could now be employed as soldiers. Hunter had previously taken a leave of absence, and General Rufus Saxton took over the responsibility.

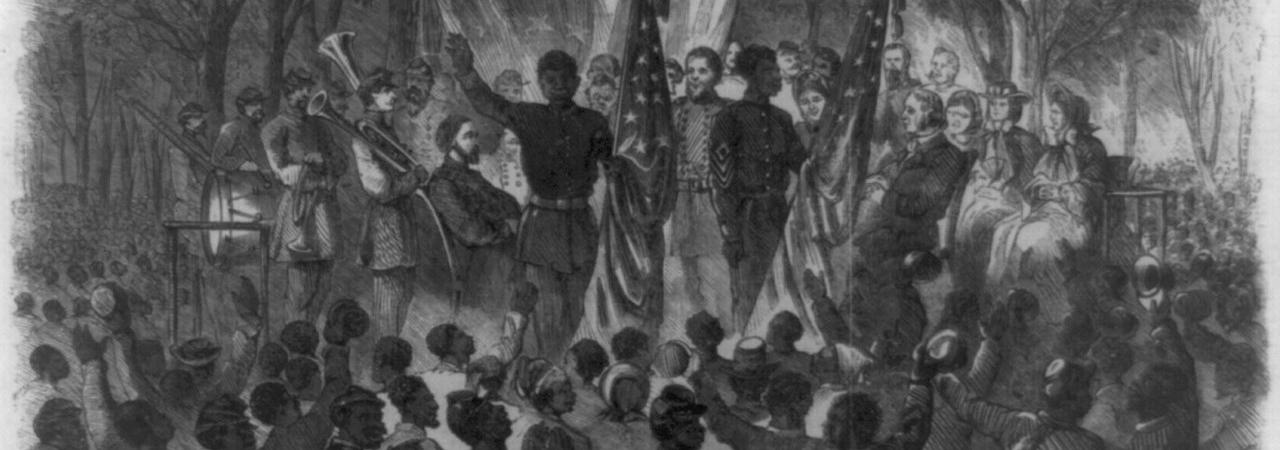

Recruiting with the promise of pay with their enlistment brought men to the ranks of the now-official regiment. Camp Saxon, named for the general, became the rallying and training point for the Gullah Geechee men who wanted to enlist. Thomas Wentworth Higginson—a committed abolitionist—took command of the regiment in November 1862. On January 31, 1863, the 1st South Carolina was officially mustered into service.

The regiment joined military expeditions near the coastal Florida-Georgia border, went up the St. Mary’s River and occupied Jacksonville. The soldiers’ knew the region well and often provided information to white officers or other regiments, too. On most of their military expeditions, the First South Carolina liberated enslaved people and helped them reach Union lines in safety.

One of the liberation moments received mention in a Massachusetts newspaper, The Recorder, in December 1863 which noted:

“On Sunday evening, Nov. 22, a scouting party of 50 men, belonging to Col. Higginson’s regiment, 1st South Carolina colored troops, was sent under the command of Capt. Bryant, 8th Maine volunteers, and Captain Whitney, 1st S.C. colored volunteers, to release 28 colored people held in pretended slavery by a man named Hayward, near Pocotaligo, S.C. The expedition was successful. The captives were released and their freedom restored to them.”

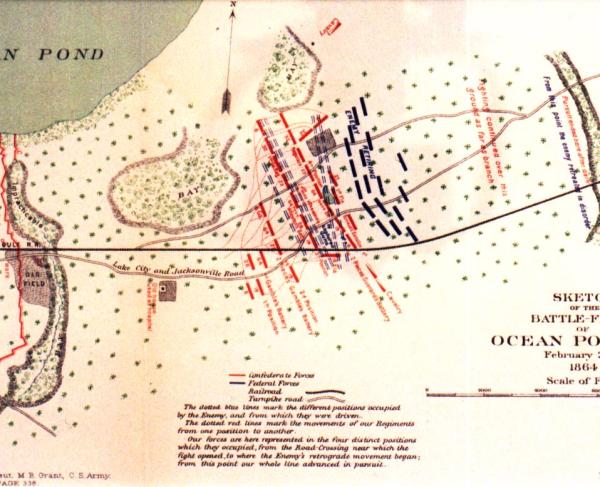

In February 1864, the 1st South Carolina received a new designation as the 33rd United States Colored Troops and served under this name for the rest of the Civil War, mustering out at Fort Wagner in 1866. They continued to serve in military operations near Charleston, South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Florida for the remainder of the Civil War mustered out of service in January 1866.

Several prominent Black women in Civil War history are associated with the 1st South Carolina/33rd USCT. Harriet Tubman, one of the best known conductors on the Underground Railroad, was with the regiment as a nurse. Susie King Taylor who fled slavery and found freedom within Union lines on St. Simon’s Island married a sergeant of the regiment; she also worked as a nurse, laundress and teacher—assisting the regiment’s soldiers and also families who sought refugee and freedom. Taylor later remembered her time at Camp Saxton, writing:

“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn. My husband taught some also when it was convenient for him. I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar. I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment, to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.”

The 1st South Carolina had a rocky start with Hunter’s good intentions but unclear communication to newly freed men and to the political leaders. Still, the early formation of the unit was an important step in challenging and changing the northern war aims to include abolition; the reports of Hunter’s proclamation and early recruiting spurred that discussion in the northern press and Lincoln’s administration. By autumn 1862 with permission to formally recruit and pay Black soldiers, the formation of the regiment became official and helped to set historic precedents for more African American men to join the Union army and fight for freedom. Recognized for their military service and discipline, the 1st South Carolina/33rd United States Colored Troops opened roads to freedom and helped to defend the concept of union.

Further Reading:

- Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War by Noah Andre Trudeau (second edition; University Press of Kansas, 2023)

- The Civil War in the South Carolina Lowcountry: How a Confederate Artillery Battery and a Black Union Regiment Defined the War by Ron Roth (McFarland Books, 2019)

- Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops by Susie King Taylor (1902)