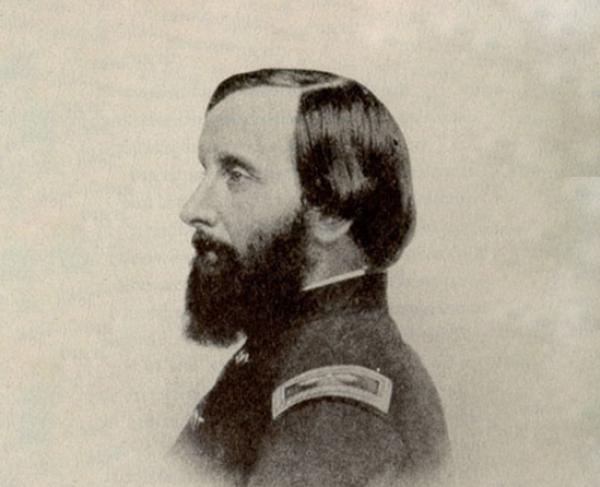

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson entered his military career fairly late in life. By the time the Civil War began, however, Higginson had been advocating for disunion for a number of years.

Higginson studied theology at Harvard Divinity School but left after a year to oppose the impending war with Mexico. Believing the Mexican-American War was an excuse to expand slavery, Higginson responded to the crisis by writing abolitionist poetry and collecting signatures for anti-war petitions. Eventually, Higginson returned to divinity school and later entered the ministry. However, his radical abolitionist sermons proved to be too much for his first congregation, and he was forced to resign.

In 1850, with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Higginson became outraged; believing that God’s law called Christians to oppose the Act, he joined the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization that protected fugitive slaves. In a sermon entitled "Massachusetts in Mourning," Higginson challenged his congregation to end the scourge of slavery by any means:

"If you take part in politics henceforward, let it be only to bring nearer the crisis which will either save or sunder this nation.”

When the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was passed, Higginson helped bring weapons and ammunition to anti-slavery settlers in Kansas. In 1857, Higginson's radicalism came to a head when he led the Worcester (Mass.) Disunion Convention. During the convention, he urged Bostonians to consider "the practicability, probability, and expediency, of a Separation between the Free and Slave States, and to take such other measures as the condition of the times may require." In 1859, leading up to John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Higginson joined a group of prominent men in financially supporting the raid, a group that came to be known as the "Secret Six." When Brown's raid failed, Higginson raised money for Brown's defense. And while the other five members of the Secret Six fled, fearing capture, Higginson refused to flee.

When the Civil War erupted, Higginson volunteered and became a captain in the 51st Massachusetts. He was wounded in August 1862 and left the 51st Massachusetts due to these injuries. After his recovery, he served as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers from November 1862 to October 1864. The 1st South Carolina would later be known as the 33rd United States Colored Troops (USCT); it was the first authorized Union regiment composed of former slaves. Along with the 54th Massachusetts, the 33rd USCT participated in the assault on Fort Wagner. In 1870, Higginson wrote about his experiences with the 1st South Carolina in Army Life in a Black Regiment.

"Until the blacks were armed, there was no guaranty of their freedom. It was their demeanor under arms that shamed the nation into recognizing them as men."

Higginson remained a powerful social activist after the war. In addition to the abolitionist cause, Higginson supported labor rights, rights for women, rights for Russian serfs, and temperance. He encouraged Susie King Taylor (teacher, nurse, and former slave) to write her own memoir entitled Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Volunteers, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteers. He also supported another female author, Emily Dickinson. After her death, he helped edit and publish Dickinson's highly unconventional poetry.

Higginson died on May 9, 1911, and was buried in Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, MA.