As war broke out between the colonies and Great Britain, the colonies were forced to adjust and evolve their military establishments. Transformation of local and colonial militias, to a more regularly trained “minuteman” force of militia to finally a professionally trained national Continental Army happened very quickly. Military necessity required American leaders to change their perceptions of standing armies and challenged their republican ideals of volunteer, part-time military service. The war saw the use of militia, minutemen, and Continental forces, but ultimately it was the Continental soldiers that would secure victory and have a lasting impact on our modern military organization.

From the beginning of European colonialization of North America, communities along the Atlantic seaboard required able body males to participate in the defense of their towns and colonies. These militia units served as the backbone of protection from Native American tribes on the frontier and foreign foes like the French. They also created a community bond that connected many far-flung neighbors. Most militias would muster and train in town and county centers, usually on court days. The events tended to have the air of a county festival, where entire communities came out to witness the drill and then host festivities afterward. Militias were the main colonial military organization for defense, but they were only part-time and very nonstandardized or professional.

As events around Boston became more tense, many communities in Massachusetts began to create more elite companies of minutemen. Militias mostly trained on a seasonal basis, but minutemen companies were established to provide more regular training (sometimes weekly) of the best men in the militia. They were expected to respond quickly to danger at a “minute’s notice.” Some of the first minutemen companies were created in Worcester, Massachusetts, in September 1774. Soon, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress adopted this organizational structure for all Massachusetts militia units in October that same year. Other New England colonies began to do the same. Some of these units were in action on April 19, 1775, but contrary to popular thought, most of the colonial units that responded that day were not minutemen companies, but regular militia.

Though most minutemen companies were formed in New England states, some similar groups popped up in other colonies. One of the more famous ones being the Culpeper, Virginia Minutemen which fought at the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775. By 1776, though, most minuteman units were disbanded with many of these members joining other units. This was due mostly to the creation of a professional army for the new nation, now the militias would serve in a support role to the Continental Army, rather than the main military force as it was in 1775.

Though considered unreliable by American military leaders and modern-day historians, militias played a very important role for the Americans in the war. Militias in areas such as New Jersey and South Carolina served as strike units against the British supply lines and attacking Loyalist units. Thus impacting the logistics of the British army and playing a key role in keeping Loyalists from playing a larger role in the war.

Militias also provided the Continental armies in the field much-needed manpower, albeit on a temporary basis. When British commanders planned for their campaigns against the Continental armies in the field, they had to take in account the size of the militia forces operating in those same geographic areas. The British knew the militia were unpredictable, but they could not totally neglect their presence either. In some instances, militia units were the deciding factors in important battles. The war’s first battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts were fought mostly by militia with some minutemen units. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, outside Boston, militia dealt a deadly blow to the British. Later in the war at battles such as Bennington, Vermont, King’s Mountain, Cowpens, both in South Carolina and Guilford Courthouse, in North Carolina, the militia was crucial to American victories.

For all the benefits of a militia force, George Washington knew for the United States to gain its independence and to create a truly nation state, a nationalized standing army needed to be created. This professionally trained Continental Army would serve as the backbone of the American war effort with militia providing support when possible.

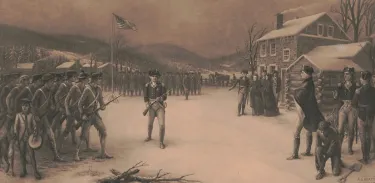

After Lexington and Concord in April 1775, thousands of militia from around New England and some mid-Atlantic states surrounded the British in Boston. Many in the Continental Congress such as John Adams called for the “nationalization” of the military forces around Boston. After some debate, on June 14, 1775, the Continental Army was created with George Washington as its commander. This was a major step for the colonies, as it now looked to create a regular standing army to oppose the British.

Initially, the militia units took time to mold into Continental units. Also, Washington had to deal with the politics of commanding officers, soldiers from a certain colony tended to want officers from their same colony. Washington did his best to navigate the issue, but his long-range goal was to create an American army, not an army based on former colony identities. This army would be under the direct control and pay of the Continental Congress, not the individual former colonies (whose control over the militias caused many issues during the war).

Washington believed strongly the only way to beat a well-trained European army was to create a professional American army in the European fashion. Washington relied on former British officers such as Charles Lee and Horatio Gates to assist him in organizing the army and begin training the soldiers. As much as Washington attempted to create a professional army, short term enlistments and lack of support from Congress which included untimely pay and lack of supplies among other issues hindered the performance of the army. The efforts of German born Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben are well known for setting up a standard training program for the Continental Army during the winter of 1778 at Valley Forge. With Steuben’s effort and Washington’s determination to create a professional army, Continental soldiers proved to be quite effective and regularly stood up to the British army as the war progressed. At the disaster at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina in August 1780, the Continental soldiers from Maryland and Delaware held out against overwhelming odds once the militia fled the field until they were completely surrounded. Continental units continued to prove their mettle in battle throughout the war.

In the beginning, Congressional leaders believed a force of approximately 20,000 men in 26 battalions would be sufficient. Quickly military and political leaders realized they would need more units and authorized more units including cavalry and artillery. Congress continued to revise and reorganize the Continental Army. One of the most significant changes were the terms of service. At the beginning of the war, terms were very short with an average of one year but as the war drew on, three years or duration of the war was required. Congress expected states to furnish “levies” as well to supplement the Continental ranks. These numbers were based on the size of the state, and many had a difficult time filling their quotas. It is difficult to determine the number of men that served as many reenlisted in the army once their terms were up. Widely accepted estimates include nearly 231,000 men served in the Continental Army, with the largest year being 1776. The army was fully integrated with nearly 6,600 people of color serving, many earning freedom from enslavement.

George Washington saw the Continental Army as the best way to mold a new nation. He saw a national army as a catalyst to remove colonial then state and sectional differences. By serving together underarms in a professional army, Washington believed the veterans of the Continental Army would serve as a nucleus of the new united republic. Today the United States Army traces its roots back to the creation of the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, but its traditions go even further back to locally raised militias and the common citizen soldier.

Further Reading

- The Minute Men: The First Fights: Myths and Realities of the American Revolution By: John R. Galvin

- A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763-1789 By: Mark Lender & James Martin

-

For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012 By: Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, William B. Feis

Related Battles

93

300

450

1,054

1,900

324

149

868

90

1,018

1,310

532