Fort McAllister State Park, Savannah, Ga.

Major General William Tecumseh Sherman was a contradiction embodied. He eliminated Atlanta's war making potential and brought sheer destruction to Georgia, then offered generous surrender terms. His vision of hard war brought the Confederacy to its knees, but forestalled thousands of battlefield and civilian deaths.

One word still resonates more deeply in the American psyche than any other in the field of Civil War study: Sherman. The name immediately conjures visions of fire and smoke, destruction and desolation; Atlanta in flames, farms laid to waste and railroad tracks mangled beyond recognition. In our collective memory, blue-clad soldiers march with impunity, their scavenged booty draped about them, leaving a trail of white women and children to sob at their losses and slaves to rejoice at their emancipation. Sherman himself is remembered through a nearly ubiquitous photograph, with a glare so icy it can chill us even across time. To average Americans, whether they are Northerners or Southerners, Sherman was a hard, cruel soldier, an unfeeling destroyer, the man who rampaged rather than fought, a brute rather than a human being.

The full story, however, is not this simple. Certainly, Sherman practiced destructive war, but he did not do it out of personal cruelty. Instead, he sought to end the war as quickly as possible, with the least loss of life on both sides.

The March to the Sea was no off-the-cuff reaction by Sherman to finding himself in Atlanta in September 1864 and knowing he could not remain there. He had for a long time hated the idea of having to kill and maim Confederates, many of whom had been pre-war friends. He wanted his army to win the war and thus preserve the Union, but he also wanted to curtail the battlefield slaughter. He sought to utilize destructive war to convince Confederate citizens in their deepest psyche both that they could not win the war and that their government could not protect them from Federal forces. He wanted to convey that southerners controlled their own fate through a duality of approach: as long as they remained in rebellion, they would suffer at his hands, once they surrendered, he would display remarkable largess.

And so, in Atlanta, Sherman instituted tactics later generations of American war leaders would use in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. In these later conflicts, largely through the use of air power, Americans attempted to destroy enemy will and logistics (a doctrine colloquially known as “shock and awe” in Operation Iraqi Freedom). On the ground and on a much smaller scale, Sherman pioneered this process, becoming the first American to do so systematically. He is rightly called the American father of total warfare, a harbinger of the psychological tactics of the next century.

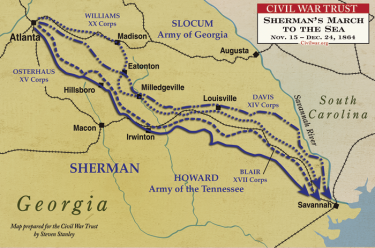

Just what was this warfare revolution? Two months after capturing Atlanta, Sherman was ready to move out and decided to strip the city of its military infrastructure. In preparation, he moved the few people remaining in the city — about 10 percent of its 20,000-person population in early 1864 — out of the area, and cut his supply line. This freed all his troops for the upcoming movement, rather than relegating a significant number for logistical duty, but this meant that the men would need to “live off the land.” From Atlanta, Sherman would set out across the Southern heartland toward the Atlantic Ocean, eventually turning north to pin Robert E. Lee’s army between his troops and those of Grant.

But the way to the sea was not open; Sherman still had to contend with the Confederate army of Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. So Sherman proposed to split his Union force, taking 62,000 of his best troops on a destructive march, while Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas used the remainder to contain Hood. Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant preferred for Sherman to destroy the Southern army first and then initiate his psychological war of destruction. But Sherman prevailed upon his commanding officer, who, in turn, convinced the president. Grant himself said that he would not have allowed anyone other than Sherman to attempt such a march — so great was the respect and trust between the two.

Sherman wasted no time. On November 15, 62,000 men — split into two infantry wings (actually four parallel corps columns) with screening cavalry to protect the main bodies as they spread across the landscape — departed Atlanta. The city was hardly burned to the ground, as Gone with the Wind implies. Not all of the destruction was even Sherman’s doing: some one-third of the city’s buildings were in ruins as a result of entrenchments dug by the Confederates and the detonation of ammunition performed as part of Hood’s evacuation. Although Sherman’s army had systematically destroyed Atlanta’s war-making potential, and had used artillery to bombard the city before taking it, 400 houses were still standing when he left.

Sherman wanted to keep his movements as secret as possible; he cut telegraph lines to prevent intelligence reports from reaching the enemy (or his superiors in Washington). Although Sherman told his officers and troops little about his plans, they quickly grasped the basic purpose of the march and, trusting their commander fully, were unconcerned about the lack of details. “Uncle Billy, I guess Grant is waiting for us in Richmond?” was a common sentiment along the march.

Georgia, stretching before Sherman’s army with its red clay hills and sandy terrain, was the largest of the Confederate states. It had some large plantations, but many more small farms growing a variety of products: vegetables, cotton, sweet potatoes and, in marshy areas, rice and sugar cane. Well known to Sherman from his study of the 1860 census, Georgia’s fertile soil still held potential to feed the ravenous Confederacy. Although beef cattle trudged along with his army, and he had his men fill their haversacks with food before they left, he knew that they could live off the Georgia land.

Those Confederate troops blocking Sherman’s way were few and weak. Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee commanded the undermanned Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, and Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith led the small Georgia state militia. The most potent Confederate force in the state was Joseph Wheeler’s 3,500-man cavalry, which managed to harass Sherman’s marchers but was too small to pose a deadly threat.

From the outset, Sherman’s men destroyed tunnels and bridges, expending particular effort to make railroad tracks unusable. The approach was backbreaking, but simple: rails were torn from the ties, which were stacked to make a bonfire beneath them. Once the rails became red hot, they were twisted into what came to be known as “Sherman’s neckties” or “Sherman’s hairpins.” The campaign’s chief engineer, Col. Orlando Poe, even devised specialized equipment, called cant hooks, for the task.

Sherman’s soldiers enthusiastically embraced his Special Field Order 120, which required every brigade to organize a foraging detachment under the direction of one of its more “discreet” officers with a goal of keeping a consistent three-day supply of gathered foodstuffs. Once, Sherman encountered a soldier walking along a road weighed down by all victuals who quoted from the order to him in a stage whisper: “Forage liberally on the country.” The general said his was a too-liberal interpretation of the order, but he took no action to punish the forager. Clearly this soldier was practicing the psychological destructive warfare against Georgia that his commander wanted.

Not only was Sherman’s army vastly larger and superior to the Confederate military, but he also outmaneuvered the few Confederate forces and kept them uncertain about his destination. He fooled the Confederates into believing that one part of his army was heading toward Augusta, while the other wing was heading for Macon. In fact, his true destination was the Georgia capital of Milledgeville. Wheeler’s 3,500 man Confederate cavalry tried to hinder Sherman’s army, but Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s 5,000 Union horse soldiers cleared it out of the way. Confederate political and military leaders — Gov. Joe Brown, Hardee and militia commander Smith among them — all fell for the ruse.

The only real combat of the March took place on November 22, near Griswoldville. The militia, temporarily under the inexperienced command of Brig. Gen. Pleasant J. Phillips, came upon part of Sherman’s rear guard of some 1,700 men. Not realizing that these Federals had repeating rifles and were dug in, temporary commander Phillips ordered his motley force to attack, and they were ripped to pieces by the Federals. After the shooting had stopped, the Union troops discovered, to their horror, that their attackers had been old men and young boys and wondered at the futility of the Confederate cause.

No matter — Sherman kept marching. To Confederate bewilderment, he bypassed Augusta and entered Confederate politician and brigadier general Howell Cobb’s plantation some 10 miles outside Milledgeville, his true destination. The capital city panicked. The state legislature extended the existing state draft to include men from 16 to 65 years of age. Those prisoners in the state jail willing to take up arms for the Confederacy — 175 out of 200 — were freed, although some of the newly liberated men burned down the penitentiary rather than report for duty. Politicians hurried to escape the city, and its civilian inhabitants were infuriated when Sherman’s men celebrated Thanksgiving there and mockingly re-enacted a legislative session to vote Georgia back into the Union. More seriously, the soldiers damaged state buildings and destroyed books and manuscripts before leaving Milledgeville on November 24. Sherman’s army had now been marching for a week.

The army moved at a steady pace, covering as much as 15 miles a day. Reveille came at daybreak and sometimes earlier. The 62,000-man army usually spent the night in tents, the campsites stretching in all directions. After a sparse breakfast, they formed the columns and began moving. Railroad tracks were upended and destroyed. Black and white pioneers cleared the path ahead, with Sherman himself sometimes joining in the physical labor. There was no lunch stop; instead, the men ate whenever and whatever they could. When they reached the assigned campsite in the evening, each man hooked his tent half to another’s, pitched it, and then prepared the only full meal of the day over a fire. The soldiers entertained themselves by letter writing, card games and other such diversions, but the favorite activity was to hear the adventures of the foragers.

As the main columns had been marching all day, organized soldiers and others fanned out in all directions, looking for food and booty. Very quickly, these foragers came to be called “bummers,” and it was they who did the most damage to the countryside and provided the most food for the troops. They wandered out five or more miles from the main columns and became experts at finding hidden food, horses, wagons and even slaves. Operating under varying degrees of supervision, their exploits formed the foundation of Sherman’s lasting reputation.

Whether it was a plantation manor, a more modest white dwelling or a slave hut, any residence encountered by these bummers stood a chance of being utterly ransacked. Barns, gardens and farms were overrun. Although many of the houses were damaged — and a minority put to the torch and totally destroyed — others were left essentially untouched, an unpredictability that became a source of great fear. “No doubt many acts of pillage, robbery, and violence were committed by these parties of foragers …,” Sherman acknowledged, but maintained that their crimes were generally against property, not individuals. “I never heard of any cases of murder or rape.” Indeed relatively few charges of rape were made, and military medical records showed little sexual disease. Still, sexual violence, especially in wartime, remains an underreported crime up to the present.

When Joe Wheeler’s horsemen also began destroying property and looting, the psychological shock of Confederates abusing their own people was hard for the Georgia civilians to take. Perhaps in denial of this reality, they came to accuse Sherman of carrying out countless grim acts. He seemed to be everywhere at once, and as he grew ever-larger in the Southern imagination, rumors about where he was and what he did to white women and slaves came to be accepted as fact. Since spreading terror farther afield only intensified the impact of his March to the Sea, all of this suited Sherman’s purposes perfectly.

The arrival of the main columns was even more frightening to the Georgians in their path than the passage of the foragers. As one Georgia woman wrote in her diary: “…like Demons they rush in! … To my smoke house, my Dairy, Pantry, kitchen & cellar.” It was difficult to hide anything from the foragers or the massive main column. Soldiers dug up buried food, valuables and keepsakes, seemingly at will. They searched hollow logs and any hiding place imaginable. Sometimes the slaves would volunteer information, and other times the foragers would force it out of them.

As the marching Federals progressed, they attracted a growing throng of ex-slaves, who greeted them as emancipators. Although he personally considered them inferior to white men, Sherman treated the blacks he met with courtesies not widespread in the 19th century, shaking hands and carrying on conversations to glean their knowledge of the area. While many blacks became laborers and performed tasks necessary to the advance, others simply followed in the wake of the column. This caused Sherman, who was trying to move quickly and live off the land, to worry about their impact on his speed and the supply of food meant for his soldiers. And even in this Union army of liberation, the racism of the age was still prevalent throughout the ranks. The former slaves grew increasingly hesitant about getting too close to the white soldiers, who might be their source of freedom, but who often treated them with harshness and disrespect. Yet, whenever they had a choice, they preferred the Federals to Confederate soldiers and civilians who had no compunction about killing them or returning them to slavery.

It was just such a conflict of interest that caused one of the most horrific events of the campaign. Acting as the rear guard for the army, on December 9, 1864, Federals under the command of Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis were crossing the flooded Ebenezer Creek on a pontoon bridge. The long line of fugitive slaves, some 650 of them, was ordered to await a signal before crossing. But as the last unit of Davis’s rear guard, the 58th Indiana, reached the far side, the bridge was unlashed. The pontoons floated away, leaving the slaves unable to cross the deep water.

Knowing that Confederate cavalry was nearby, the fugitives, fearful of being captured and killed or re-enslaved, panicked. They jumped into the water, frantically trying to swim across and evade Wheeler. Seeing their terror and desperation, some Federals began throwing logs and anything else they could find toward the drowning people. Although some were saved on makeshift rafts or by soldiers who waded into the creek, a huge number drowned and others were captured by the arriving Confederate troopers. Davis, who was no stranger to scandal — he was arrested for murdering fellow Union general William Nelson in August 1862, but escaped court martial — took a great deal of blame for this horror, but Sherman defended him. He blamed the ex-slave refugees for ignoring his advice not to follow the army.

Two weeks after this incident, and 20 miles removed, the march ended in Savannah. Sherman’s army reached the sea, took Fort McAllister and re-tied itself to a naval supply line. On December 21, Union forces captured Savannah; Sherman presented the city to Lincoln as a Christmas gift.

Almost miraculously, damage and destruction immediately ceased. Sherman allowed Hardee’s army to escape the city, although he could have crushed it. Soldiers became model gentlemen, no longer foraging, but paying for what they wanted or needed. Sherman had his favorite regimental band present a concert for the city and brought supply ships from the North to help the city and its people regain a sense of normality. The general himself was a model of deportment. In escaping Savannah, several Confederate generals left their wives and children to Sherman’s personal protection, and he took this responsibility seriously, despite laughing that Confederates were willing to leave their families in the care of someone they considered a brute.

It was a strange end to a destructive month, but perhaps it should not have been unexpected. When Sherman instituted his destructive war, he told Southerners that as long as they continued their resistance, he would make them pay dearly, but that the process would stop when they quit the fight. As soon as the mayor of Savannah surrendered his city, Sherman the fiend became Sherman the friend.

When it came time to march through the Carolinas, states still in rebellion against the United States, however, destructive war returned. In fact, South Carolina suffered more at Sherman’s hands than Georgia had during the March to the Sea. Sherman demanded surrender, and he would accept nothing less, so his men tore through the Palmetto State. North Carolina suffered less because it was not viewed as responsible for the rebellion, as South Carolina was. When Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered at Durham Station, N.C., in April 1865, Sherman offered a peace plan lenient enough that it caused many in the North to question his loyalty. In reality it was a final iteration of his campaign to show mercy immediately upon surrender.

In short, the March to the Sea demonstrates not that Sherman was a brute, but that he wanted to wage a war that did not result in countless deaths. He saw destruction of property as less onerous than casualties. It is estimated that during the six-week March to the Sea fewer than 3,000 casualties resulted. Compared to the 51,000 killed, wounded and missing at Gettysburg in the three days of fighting there or the 24,000 in the two days at Shiloh, the month-long March to the Sea was nearly bloodless.

Yet, the March is remembered to this day as barbarism unleashed. There was glory to die in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, but only humiliation to have one’s barn burned, silverware taken, house damaged or destroyed, or horses added to the enemy cavalry. Sherman successfully fought a psychological war of destruction. He entered the Confederate psyche and remains in some minds to the present day.