Savannah

In 1778, the British succeeded in capturing Savannah, Georgia as part of a larger plan to shift the focus of the war from the North to the South. British policymakers and strategists believed that the large Loyalist population in the southern colonies would embrace their actions. In 1779, the first test of the American-French alliance took place as the combined forces attempted to retake the city in one of the bloodiest engagements of the War for Independence.

From September 16 to October 18, 1779 the Franco-American forces worked to dislodge the approximately 7,000-man British garrison led by General Augustine Prevost. The British had constructed an extended entrenched defensive position, which included several redoubts to defend the city, particularly in its front which faced a large, open plain. To help complete the defenses, the British relied on local slave laborers who worked twelve hours a day to beef up the defensive perimeter. By the end of the siege, the British had over a hundred pieces of artillery placed along their line.

American forces in the south, between 5,000 and 7,000 men, were based at Charleston under the command of General Benjamin Lincoln. Lincoln recognized that he would need assistance from the French navy and army to retake Savannah. On September 3, he learned that the French forces under the command of Admiral Comte d’Estaing were en route to Savannah, bringing with them ships-of-the-line and 4,000 soldiers. On September 11, Lincoln marched out of Charleston with 2,000 Continentals to link up with d’Estaing. Arriving first, d’Estaing began offensive operations to take the city. He initially offered Prevost an opportunity to surrender, but Prevost demurred, hoping that reinforcements would arrive. He was given twenty-four hours. This reprieve would prove in the end to be pivotal, as 1,000 men arrived to support Prevost's force just as Lincoln arrived to support d'Estaing. The Allied forces, when fully assembled, numbered near 7,000. Defending Savannah was a force totaling 2,500 men. Faced with overwhelming odds, Prevost organized a solid defensive plan.

With the situation remaining fluid, the American and French commanders held a council of war. Lincoln reluctantly ceded de facto command to d’Estaing, who had begun operations before Lincoln’s arrival. The French commander believed that a frontal assault against the British position would be futile and instead proposed to bombard the city. Lincoln concurred, French cannons were removed from their ships, and a five day cannonade began. However, Savannah bore the brunt of the artillery assault while the defensive positions remained relatively untouched, so d’Estaing eventually agreed to the frontal assault in spite of objections by his officers. He worried that a protracted siege would take too long and wanted to redeem his glory that had been tarnished at Newport, Rhode Island. Additionally, hurricane season was moving in and the British fleet was still lurking somewhere off the coast nearby.

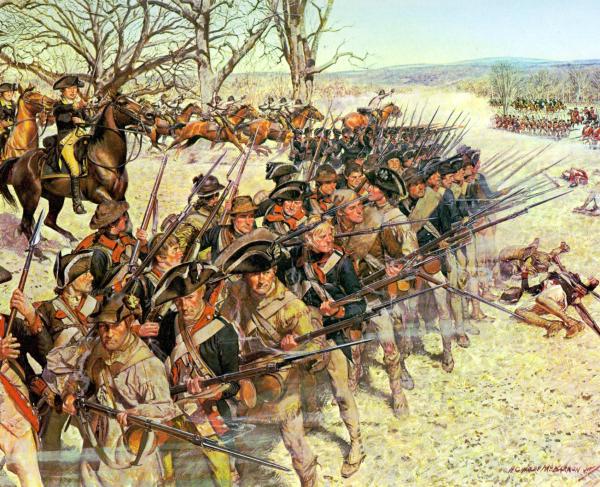

On the morning of October 9, the Franco-American assault began. Preparations had been held in secret, but Prevost gained critical intelligence prior to the scheduled 4:00 am advance that gave him an edge. Fog shrouded the battlefield and impeded forward progress as troops got lost in the swamps in front of the redoubt they were attacking. This redoubt, the Spring Hill redoubt, had been selected by d’Estaing because he erroneously believed it to be only lightly defended by local Loyalist militia. In reality, that militia was backed up by battle-hardened British Regulars. Admiral d’Estaing also failed to engage in any serious reconnaissance of British positions.

Once the fog lifted, the French lines were fully exposed and crumbled in the face of a withering and incessant fire from the defenders. d’Estaing himself received two wounds as he personally led the attack. Mortally wounded in the first assault was the Polish Cavalry mastermind, Casimir Pulaski, who had done much to shape the American cavalry forces of the Continental army. He was shot trying to lead horsemen through a brief breach that appeared in the British lines. The first wave faltered in front of the English breastworks, the trenches in front of them filling up rapidly with French bodies. One British officer later recalled that a trench, “was filled with mangled bodies and the ditch filled with the dead.” When the second wave moved, it was held up by the chaos of the faltering first wave. Fierce fighting took place up and down the line of battle and in several instances Americans and French reached the breastworks and were able to plant the colors, only to be pushed back. A Swedish Count, Curt von Stedingk, serving with French forces later wrote, “I had the pleasure of planting the American flag on the last trench, but the enemy renewed its attack and our people were annihilated by cross-fire. The moment of retreat with the cries of our dying comrades piercing my heart was the bitterest of my life.” The allied forces suffered about 1,000 casualties. The British casualty rate was only about 150 men.

An hour after leading forces forward, d’Estaing called off the attack, recognizing its futility. A week later d’Estaing sailed away, leaving Lincoln behind and the Franco-American Alliance strained. The siege was lifted by Lincoln’s forces on October 19. Savannah would remain in British hands until the end of the war.