Slaughter Pen Farm, Fredericksburg, Va.

On land known as the “Slaughter Pen,” the Battle of Fredericksburg was both won and lost on December 13, 1862. As outnumbered, blue-clad troops marched across the ground, they encountered horror like never before. Despite performing a number of gallant actions, the Federals were outmatched, ultimately placing victory in Confederate hands.

The Battle of Fredericksburg is misunderstood, its intricacies brushed off and reduced to a futile frontal assault against a fixed position, with Confederate soldiers well positioned for easy victory, mowing down thousands of Federal soldiers. The reality of what happened on December 13, 1862, is far different. It was a two-front fight: One-sided carnage, indeed, at Marye’s Heights, but a close-fought thing to the south, where the Union army was on the cusp of dislodging and possibly defeating Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The plan that Federal commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside decided upon was simple enough: a pre-dawn, nearly simultaneous assault on the Confederate lines. On the Union left, Burnside amassed nearly 65,000 Federal soldiers to attack across a plain south of Fredericksburg, strike the Confederate right and push it to the west and north — away from the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. “The enemy had cut a road … in the rear of the lie of heights … by which they connected the two wings of their army,” Burnside later told the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, “I wanted to obtain possession of that new road, and that was my reason for making the attack on the extreme [Federal] left.” Immediately following the seizure of the road, Burnside intended to launch the assaults on the Rebel left and right, which would “stagger the enemy, cutting their line in two.” When the “direct attack on their front,” drove the Confederates from their works. Burnside could then pursue the disorganized enemy or interpose his army between Richmond and Lee’s army.

Vague orders arrived at the front after dawn on December 13, and they seemed to contradict the plan Burnside had discussed with his commanders the previous evening. The Federal commander in charge of the Union left, Maj. Gen. William Buel Franklin, was baffled. He had assumed his men would be the vanguard of the offensive, yet the orders he received sounded impotent. “The general commanding directs that you keep your command in position for a rapid movement down the Old Richmond Road, and you will send out at once a division at least to pass below Smithfield, to seize, if possible, the height near Capt Hamilton’s … taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.”

Rather than ask Burnside for clarification, Franklin stuck to what he perceived as the tone of the order and, instead of launching 65,000 Federals on an assault, he sent forward “a division at least” — some 4,200 men — and he kept “it well supported” with another division of some 4,000 soldiers. Simply put, a poorly worded order and terrible communications — all made worse by a bad map — led to Franklin’s decision to throw forward a mere 8,200 men — a fraction of what were at his disposal — toward an enemy line of more than 38,000 Confederate soldiers.

Why would Franklin not ask for clarification? According to the Left Grand Division commander [Franklin], General-in-Chief Henry Halleck informed him prior to the battle that he “would be tried as soon as they were through with Fitz John Porter.” Porter was Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s favorite corps commander during the Peninsula Campaign and Seven Days Battles. He’d been relieved of command and was about to face a military tribunal for actions at Second Manassas. Franklin, another of “Little Mac’s” favorites, was next on the chopping block. Thus, as one of the highest-ranking officers entering the Battle of Fredericksburg, he feared for his career. This led to Franklin going out of his way not to make waves or think outside the box. He stuck to the letter of the order.

William Buel Franklin was born on February 27, 1823 in York, Pennsylvania. He attended West Point from 1839 to 1843, graduating first in his class. He...

In 1862, the fields south of Fredericksburg were open and slightly rolling. A handful of men owned most of the land along the Richmond Highway (present-day Routes 2 and 17). Alfred Bernard owned the 911-acre plantation known as the Bend, while his brother Arthur owned some 1,800 adjacent acres at Mannsfield Plantation. Farther to the south stood Smithfield (today the Fredericksburg Country Club), then owned by Thomas Pratt and consisting of 1,750 acres. It was largely across these three plantations that Franklin's men arrayed for battle.

As the blanket of blue engulfed the plantation fields, one Confederate opined. “It was a grand sight seeing them come in position this morning, but it seemed that host would eat us up.” The Federal formation was not as imposing as it seemed, however. Near 10:00 a.m., a few stray cannon shots fell among the Union ranks, originating not from the far tree line but from the Union left, where there should be no Confederates. A Pennsylvania soldier stated, “Naturally supposing, from the position [of the cannon], ’twas one of our own batteries, we thought our gunners had had too much ‘commissary’ this morning, and so remarked.” Yet the shots kept coming, not from a few inebriated Union artillerists but instead a rogue Confederate officer. Maj. John Pelham of Stuart's Horse Artillery had ridden forward with a lone cannon and pelted the Union flank for nearly an hour, stalling the Federal offensive.

Around noon, the Federal offensive lurched forward once more. This time, the Confederates responded with a roar. The full force of Southern artillery, some 56 cannons, came to bear on the Federals, who were easy targets on an open plain. Federal artillery countered in an artillery duel not topped in the war’s Eastern Theater until Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg.

Spearheading the Federal advance was 47-year-old Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. A Pennsylvanian and West Point graduate, Meade was one of the finest combat officers in the Army of the Potomac. His division of Pennsylvania Reserves were, by December 1862, veteran soldiers. The normally no-nonsense Meade, the “goggled-eyed snapping turtle,” was in fine spirts as the man-made hurricane of Confederate shot and shell pierced the air and earth. It was a front, a lie. Meade did everything to bolster the men's spirits. He rode over to Col. William “Buck” McCandless and inquired, “A star today, William?” referring to his promotion to general. Just then, a shell gutted the colonel’s horse. McCandless retorted, “More likely a wooden overcoat.” The two men laughed and moved on.

Around 1:00 p.m., two Confederate ammunition chests exploded along the Southern lines in rapid succession. Some Federals leaped to their feet and cheered wildly. Meade called all his 4,200 Pennsylvanians to their feet, and they pressed forward into a point of woods and flowed onto a low rise called Prospect Hill. Although outnumbered, Meade’s men burst like a shell in all directions and, amazingly, breached the dense Confederate line. They desperately needed support, though.

Although his family lived in the South, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon felt compelled by duty to stay with the Union, where he amassed a stellar reputation as the leader of the famed Iron Brigade. On the afternoon of December 13, he stood at the head of an entire Union division. As Gibbon steeled himself for battle, he could not have known that the Confederate force he was about to assault — across what has been dubbed as the “Slaughter Pen” of Fredericksburg — contained three of his brothers.

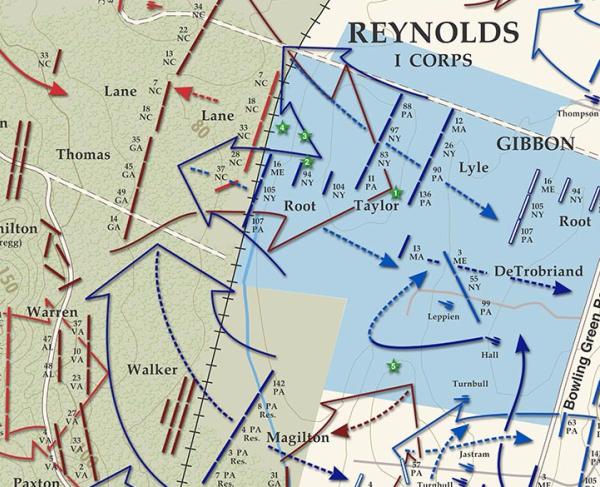

As Meade’s men fought for their lives atop Prospect Hill, Gibbon readied his division for action, stacking his three brigades one behind the other, with two online and his third in a “close column of regiments.” This Napoleonic era tactic offered advantages to both the attacker and defender. The formation could act as a battering ram, while at the same time allowing Gibbon to swing brigades to the left or right of his lead brigade and also offer close support of the frontline troops. Conversely, the formation allowed the defender to outflank and encircle this formation (as had happened in the West Woods at Antietam), while also giving the Rebel artillerymen a target with great depth.

At about 1:30 p.m., Gibbon’s first wave trudged across the marshy, muddy field that sought to suck the shoes right off the men’s feet. Their wool uniforms were made heavy by the water they had absorbed while the men lie in the open, waiting to go into action. Gibbon’s soldiers advanced “on a double-quick over a rough road and high fence, midst the whistling shot and shell … the noise was terrific, almost deafening.”

Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor, Gibbon’s senior brigade commander, found that the seemingly flat field the men were trudging through was not so flat. The plantation fields across which they advanced had several fences. The traditional wood fence along the road offered little difficulty; rather, the ditch fence they came across in the field posed a major issue. Farmers in that part of Virginia dug ditch fences to provide irrigation for their fields, denote property lines and keep cattle from wandering. One Third Corps officer wrote that the “meadow [was] intersected by two parallel ditch-drains from five to six feet deep, with steep sides, and at many points almost impassable.” This particular fence was also around 10 feet wide. The width of the fence meant the muddy Federal soldiers could not leap across it — they had to jump into more mud and ankle- to knee-deep water. Once out of the ditch fence, the men ascended an almost-imperceptible rise, dubbed a “slight elevation" by Gibbon.

Once atop, Taylor’s lead brigade felt the full brunt of the Confederate small-arms fire. Four of the five North Carolina regiments led by Brig. Gen. James Lane opened upon the exposed Federals. (These were the same Tar Heels who would wound Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in a friendly fire incident six months later.) Taylor attempted to steady his men, who began falling left and right. “A severe fire was at once opened … by the enemy,” who was “posted behind the railroad embankment and in the wood.”

The defensive line of Jackson’s Second Army Corps ran roughly north to south for approximately two miles. Jackson, an excellent attacker but a poor defender, established a defense in depth along his sector of the Confederate line. His portion of Lee’s overall position at Fredericksburg was much weaker geographically than Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps sector. Jackson’s position lacked the numerous natural and artificial obstacles facing the Yankees on the north end of the field. The low-rising Prospect Hill; Deep Run to the south; woods; and the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad embankment offered Jackson’s men some protection. But a swamp made it impossible for Jackson to run a continuous front line, leaving a 600-yard indefensible gap in his front line. To bolster this position, Old Jack had his men construct earthen fortifications, and he stacked his divisions one behind the other.

On the Federal side, Taylor’s attack foundered. Standing in an open field, exchanging shots with an enemy protected behind the railroad embankment and in the tree line, was a losing proposition. To make matters worse, the left of Taylor’s line stood on the exposed knoll taking heavy fire, while the right was in a lower piece of ground, unable to bring its full weight of fire upon Lane’s North Carolinians. Adding to Taylor’s woes, the 88th Pennsylvania on the right of his line was ordered forward to fire into an enemy battery. Upon executing this command, the Pennsylvanians became “frightened at the noise they had made themselves, with a few exceptions the whole regiment turned and ran toward the rear.” Taylor and one of his aides managed to rally the 88th Pennsylvania, but it took some time and reduced the effectiveness of his force.

After 20 minutes of fighting, the left of Taylor’s line ran low on ammunition. Gibbon called upon Col. Peter Lyle’s brigade to add its weight to the Federal frontline. Once at the front, Lyle found half of Taylor’s men streaming to the rear. The latter’s right two regiments, the 11th Pennsylvania and the 83rd New York, stood and exchanged fire until their ammo boxes were empty. With the arrival of Lyle’s men, the New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians felt that their job was done.

Taylor brought his other two regiments still on the field, the 88th Pennsylvania and the 97th New York, online with Lyle’s men. The line of six regiments inched closer to the sheltered Confederate line. Lyle’s battle line faltered as his men pressed across the field. Confederates leaped atop the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad embankment and singled out many of the Federal color bearers. The color bearer of the 26th New York Infantry fell wounded as the unit advanced across the Slaughter Pen. The men of the 26th had already entered the battle with a pall over their heads. Their former colonel, William Christian, had resigned from the army in disgrace, labeled as a coward. Thus, the soldiers of 26th New York had something to prove at Fredericksburg.

As their colors fell, a German immigrant sprang forward. Sickly Martin Schubert should not have been on the battlefield at Fredericksburg, having just received a medical discharge from the army. But instead of abandoning his comrades in their time of need, Schubert had stayed to fight. Now, he scooped up the flag and, rather than just stand his ground, he strode forward, urging his unit to follow. Moments later, Schubert fell wounded — but another immigrant stepped in to take up the colors and the advance. Joseph Keene, born an Englishman, took the flag from Schubert and helped to keep the advance going. Both Schubert and Keene received the Medal of Honor.

Down the line from the 26th New York was the brand-new 136th Pennsylvania Infantry. These nine-month soldiers, who hailed from western Pennsylvania, had joined the Union cause when President Lincoln called for 300,000 more men in response to Robert E. Lee's move into Maryland earlier in the fall.

The fight at the Slaughter Pen was overwhelming for some of the green Keystone Staters. The color bearer of the unit was a 250-pound man who made a perfect target for the Rebels. As this fact dawned on him, he abandoned his flag. Phillip Petty saw the discarded banner and snatched it up. Like Schubert, Petty led by example and moved forward with the flag, helping to urge his men across the field. He stomped on for a few yards, planted the flag in the ground, knelt beside it and fired on the enemy. His fellow Pennsylvanians rallied around him. Petty was later presented with the Medal of Honor.

Meanwhile, John Gibbon added the weight of his third and final brigade to the attack. Col. Adrian Root’s five regiments moved to the front. Exposed and “[f]inding his fire very disastrous, and seeing that our fire was doing little or no execution, the order was received … to fix bayonets, charge, and drive him from his breast-works.” Gibbon was wounded in the wrist and turned command over to Nelson Taylor. In the meantime, the 16th Maine entering its first battle and “15 paces in advance of those” on their left and right, surged toward the wood line. Gibbon’s depleted division followed. “The brigade charged up to the railroad in the face of a close and telling fire from the enemy,” said Maj. John Kress of the 94th New York.

Yankees and Rebels fought hand-to-hand, crossing bayonets and swords along the railroad cut, while clubbed muskets swung wildly along the lines. Otis Libby, “of Company H [16th Maine] crazed with pain from a wound in the head by a clubbed musket, ran two rebels through with his bayonet, and heedless of the fact that his enemies had surrendered”; only an officer removing the crazed soldier from the front stopped the private.

The Federals drove into the woods, scattering Lane’s Tar Heels. Unfortunately for the Yankees, they were met by some of the best units in Lee’s army. On the Federal right, the guns of Joseph Latimer’s and Greenlee Davidson’s batteries stopped their momentum along the railroad embankment. The 16th North Carolina of Brig. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’s brigade even sallied forth to fire into the Federal flank. The brigades of Gens. Alfred Scales, Edward Thomas and Lane struck back in the woods. Gibbon’s division shot its bolt and began withdrawing to the embankment and back into the open fields strewn with dead and wounded.

In the pell-mell retreat, scores of Union prisoners fell into Rebel hands; Pvt. George Heiser of the 136th Pennsylvania was among those unlucky men. Heiser had refused to leave a wounded comrade near the rail line. Confederates sent him to Libby Prison, although he was later exchanged. Heiser survived his nine months with the army and was incredibly proud of his service. He participated in veterans’ reunions, marched in memorial parades and instilled the pride of patriotism in his son Victor. George owned a store in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, filled with everything necessary to live in coal country and operated with utter generosity: If you couldn't afford to pay, George Heiser let you take what you needed anyhow — he knew you were good for it. Tragically, in May 1889, two days after marching in the annual memorial celebration, George and his wife, Mathilde, were swept away in the waters of the epic Johnstown Flood. Fifteen-year-old Victor Heiser miraculously survived and, after the flood waters receded, went to where his parents’ store had once stood: All that remained was a wardrobe. He opened it to find the contents: his father’s Civil War uniform. In the pocket, Victor found the entirety of his inheritance — one cent — perhaps carried by George at Fredericksburg. George Heiser had survived the horror of the Slaughter Pen at Fredericksburg and the hell of Libby Prison only to die in one of the other great tragedies of the late 19th century. Victor became a local doctor and was remembered for having the same giving heart as his father.

With Meade’s and Gibbon’s attacks both over, now it was a matter of survival. Meade begged for reinforcements. Then he pleaded for them. Finally, he went on the warpath with fellow Union officers. After far too much time, reinforcements arrived at the front, but the ever-aggressive Jackson launched counterattacks off Prospect Hill and into the Slaughter Pen Farm.

Fresh Union troops entered the field as the Confederate counterattack reached its zenith. Col. Charles Collis was a native of Ireland who had immigrated to the United States shortly before the Civil War. Collis served in the 1862 Valley Campaign and seemed to have solid battlefield acumen. His unit, the 114th Pennsylvania, was known as “Collis’s Zouaves” because they wore flashy red and blue uniforms modeled after French Algerian soldiers. Unfortunately, they were entering their first battle. They looked the part for a role they would struggle to fill.

What the Pennsylvanians saw was akin to pandemonium. Their brigade commander, John Robinson, was knocked out of action, and Gibbon’s men were fleeing into the fields with Confederates in hot pursuit. Federal batteries were about to be overrun. Collis didn’t flinch. He rode to the center of his line, snatched the flag from the color bearer and spurred his horse forward, bellowing, “Remember the stone wall at Middletown!” While the phrase might have been invigorating to other soldiers, the 114th Pennsylvania had not fought at Middletown. Thus, the meaning of the phrase was lost. What did spur the men of the 114th Pennsylvania forward was the action of the colonel, on horseback, flag in hand. The Keystone State men slammed into the Confederates, halting the Rebel counterattack. The moment was immortalized in a massive painting, while Collis’s heroism earned him the Medal of Honor.

Marching into battle with the men of the 114th Pennsylvania, but often overlooked, was a vivandière named French Mary Tepe. Like a Zouave, a vivandière was a carryover from the French army, in this case woman who supported soldiers in the field by supplying them with water, aid and other care. Tepe was right behind the battle line in the Slaughter Pen when she was wounded in the ankle. For her actions, she was awarded the Kearney Cross, an award exclusively presented by Gen. Philip Kearney’s old division. The cross was granted “only to brave and worthy soldiers.”

By 3:00 p.m., the fighting at the Slaughter Pen was all but over, nearly 5,000 soldiers having fallen in the life-and-death struggle. Across that bloody plain, and in a radius of some 400 yards, five men “received the highest and most prestigious personal military decoration that may be awarded to recognize U.S. military service members who distinguished themselves by acts of valor” — the Medal of Honor. Few sites of battle ever witnessed this amount of horror and heroism in such a small span of time and space.

Upon retreating across the Rappahannock River, one Pennsylvania soldier seemed to sum up the experience of every Federal soldier who fought at the Battle of Fredericksburg and survived. “I am free to confess that the moment I touched the earth I drew a long, strong and soul-relieving breath, and from the bottom of my heart, thanked God that I have lived to get out of that infernal slaughter pen and was once more safely landed on the other side of Jordan.”

To restore land and history at Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Slaughter Pen Farm and New Market Heights, we must raise $131,000. Please help to finish the...

Related Battles

12,500

6,000