Bennett Place Surrender

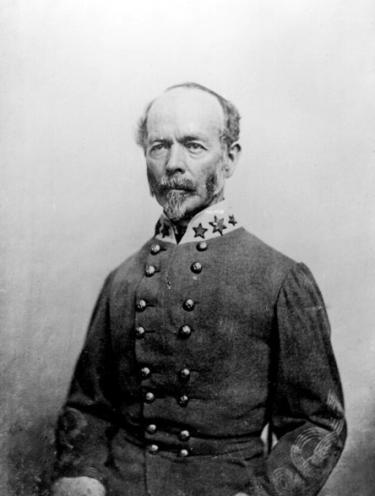

On April 11, 1865, at 1 o’clock in the morning, General Joseph E. Johnston learned from an unofficial yet reliable dispatch that General Robert E. Lee surrendered the remnants of his army near Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Prior to this, the last shred of hope for an independent and the victorious Confederate States of America rested on Johnston uniting his army with Lee’s somewhere near the North Carolina-Virginia border. Lee’s surrender dashed these hopes.

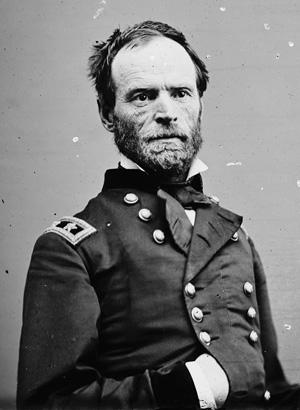

However, even after official confirmation from Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckenridge on April 12, President Jefferson Davis remained unconvinced that Lee’s surrender was the fatal blow to the Confederacy and the war effort. Rather, Davis spouted these grand illusions of a raising a large, well-armed, well-fed field army comprised of recalled deserters and those who avoided conscription to continue the fight for Confederate independence. On April 13 during a military meeting in Greensboro, North Carolina, Johnston tried to dissuade Davis from his plan for renewed combat by arguing that the Union forces outnumbered the Confederates by eighteen to one, the Confederacy lacked the money, credit, and factories to purchase or produce more arms, and fighting would only further devastate the South without significantly harming the enemy. With the surrender at Appomattox, Johnston shifted his objective to procuring the best possible terms for surrender as he argued: “it would be the greatest of human crimes to continue the war.” Luckily for Johnston, Davis agreed to open communications with General William T. Sherman; however, Davis still believed that victory was achievable despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Johnston received Sherman’s reply on Easter Sunday morning and rode out to Greensboro to notify Davis; however, Davis had left without notifying Johnston—the two men never enjoyed a cordial relationship. An annoyed Johnston decided to engage in negotiations with Sherman without Davis’s authorization and suggested meeting on April 17, which Sherman agreed to.

As Sherman boarded his train in Raleigh to take him to Durham Station (modern-day Durham, NC) on the morning of April 17, Sherman learned by a coded telegram from Federal Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated. Despite this shocking news, Sherman continued with his plans to meet with Johnston. Sherman and Johnston had never met before, despite both serving in the Old Army; however, both developed a mutual respect for one another during the Atlanta Campaign. After exchanging pleasantries, the generals settled on the small Bennett farmstead to house their private meeting to negotiate the terms of surrender. As soon as they were in private, Sherman handed Johnston the telegraph announcing Lincoln’s assassination. After hearing the news, Johnston told Sherman he believed “the event was the greatest possible calamity to the South,” which reaffirmed his goal of obtaining the best possible terms of surrender. In these preliminary negotiations Johnston played his trump card, he offered to negotiate the terms of the surrender of all the remaining armies in exchange for amnesty for Davis and his cabinet, which Johnston claimed he could receive Davis’s authorization. Sherman initially rejected that offer as he not only promised Grant he would not deviate from the terms Grant offered Lee at Appomattox but also because by agreeing to Johnston’s terms Sherman would recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign independent nation and extend into civilian matters which transgressed the boundaries of Sherman’s authority as a military commander. The two parties agreed to meet the following day for further negotiations.

When Sherman returned to Raleigh he learned that despite his order to the contrary, the news of Lincoln’s assassination spread. Sherman encountered an angry mob of soldiers who demanded that Sherman refuse a Confederate surrender; these men were “crazy with vengeance.” The town of Raleigh was almost burned to the ground (a-la Columbia) during the night of April 17-18, yet Sherman was able to maintain control of his army and their quest for revenge. While the Union Army of the Tennessee was close to turning into a mob, the Confederate Army of Tennessee was quickly crumbling away at the seams. As news of the surrender negotiations spread, demoralization spread across all units of Johnston’s army which in turn spurned high numbers of desertions. The Army of Tennessee was quickly becoming a skeleton army.

On April 18 at noon Johnston and Sherman met once again at the Bennett House. Johnston, through Breckenridge, obtained Davis’s authorization to surrender the remaining Confederate armies but wanted Sherman’s explicit assurance for the protection of his soldier’s Constitutional rights. Sherman assured him that Lincoln’s 1863 Amnesty Proclamation and the terms of the Appomattox surrender allowed for a full pardon of all Confederate soldiers, from privates to the commanding general. Sherman and Johnston eventually reached an agreement. Under this agreement, hostilities would be suspended pending approval of the agreement, Confederate arms were to be deposited in the respective state arsenals and could only be used within that state, and officers and men had to sign an agreement to cease all hostilities of war. Additionally, the President of the United States would recognize all southern state governments as long as their officers and legislators took an oath of allegiance, the federal court system would be reestablished in the southern states. The President would also guarantee the personal, political and property rights of the Southern people and grant legal amnesty to all southerners, which implicitly included Davis and his cabinet. These terms were incredibly lenient to southerners and followed Sherman’s policy of a hard war followed by soft terms. Sherman did not want to punish the South but rather welcome them back into the fold of the United States with open arms to alleviate any resistance. Regardless his motivations, by offering these terms Sherman delved into political matters which he had no authority over. For this reason, President Andrew Johnson and his cabinet rejected these April 18 terms and sent Grant to Raleigh to oversee the resumption of hostilities.

During the armistice, Johnston’s skeleton army was further crumbling as mass desertions increased which continued to plague the army. Discipline collapsed and thievery ran rampant, even Johnston’s headquarters were robbed. Johnston and his subordinates barely had any control of the army. Thus, when a dispatch from Sherman arrived at six o’clock in the evening on April 24, notifying him that hostilities would resume on April 26 at noon sharp, Johnston knew he needed to act fast in order to procure favorable surrender terms for his quickly shrinking army. At Johnston’s request, he and Sherman met again at the Bennett Place on April 26 without Grant. Under Johnston and Sherman’s authority, General John Schofield drafted terms that closely resembled the Appomattox terms. On April 27, Johnston wrote a codicil for these terms which Schofield amended. President Johnson and his cabinet approved these terms and did not take issue with Johnston’s supplement. Under these final terms, Johnston’s army and his naval force would cease all hostilities, each brigade could keep 1/7 of its small arms and soldiers would deposit their arms at their respective state capitols, all officers and men were to be paroled and take an oath to not take up arms against the United States, their paroles would be signed by their immediate commanders, soldiers could retain their horses and other private property, and the Union army would provide field, rail and water transportation home to paroled men. Separate from this agreement, Sherman also promised 250,000 rations to the newly paroled troops. These favorable surrender terms allowed former Confederates to return home with relative ease.

The surrender at Bennett Place was the largest surrender of the entire war, which included approximately 90,000 Confederates stationed in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. However, Bennett Place was not the last Confederate surrender, that occurred on June 23, 1865, with General Stand Watie’s Indian Territory troops. However, the surrender illustrates the tensions between military and political leaders and represents the struggle to bring the former Confederates back into the Union fold while ensuring the prevention of any future hostilities.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

1,527

2,606