The Jim Crow Era

In 1877, the newly inaugurated President Rutherford B. Hayes removed the last armed troops from the former Confederate States of America. Since the end of the war, military outposts had been placed throughout the South to distribute aid, maintain order, and ensure that residents adhered to the newly implemented Reconstruction Amendments. These amendments included the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery; the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship regardless of race; and the 15th Amendment, which granted the ability to vote regardless of race. All Southern States were required to ratify these three amendments before they could reenter the United States. However, there were factions of the South that disagreed with these new amendments and equality between black and white individuals. As the Reconstruction era ended in 1877 and oversite lessened, many wanted to recreate the antebellum race relations between black and white individuals. In order to recreate this social status, “Jim Crow Laws” were established that limited African American's political and social rights in the Southern States. This era of racial discrimination lasted well into the twentieth century and did not end until 1965.

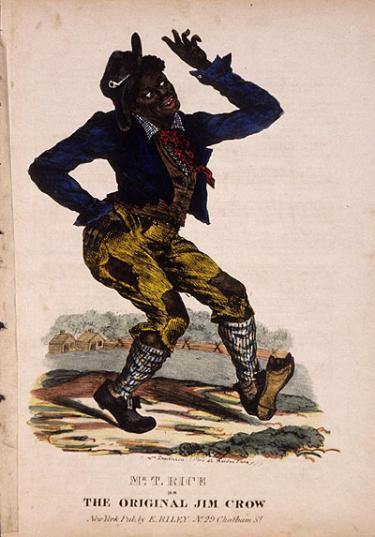

“Jim Crow Laws” get their name from a character created and performed by the “father of American minstrelsy” Thomas D. Rice in the 1830s. Rice claimed that “Jim Crow” was modeled after a disabled black slave who sang and danced as he worked. Finding the singing and dancing comical, he bought the clothes from the slave in order to be “realistic” in his portrayal and adopted the folk song “Jump Jim Crow,” which was commonly sung by slaves, for his act. To appear African American, Rice rubbed burnt cork on his face. The public loved Rice and his Jim Crow character. From the 1830s to the 1850s, Rice traveled around the country performing in minstrel shows. These shows consisted of comedic skits, songs, variety acts, and dancing and commonly perpetuating negative stereotypes of African Americans for entertainment. With Rice’s popularity, minstrel shows became a leading form of entertainment until the Civil War and other performers began to copy Rice’s character and styling. The practice of rubbing cork on his face became known as “blackface” and became a standard addition to the shows. “Jim Crow” became shorthand for “African American” and lasted well after Rice died and minstrel shows lost their popularity.

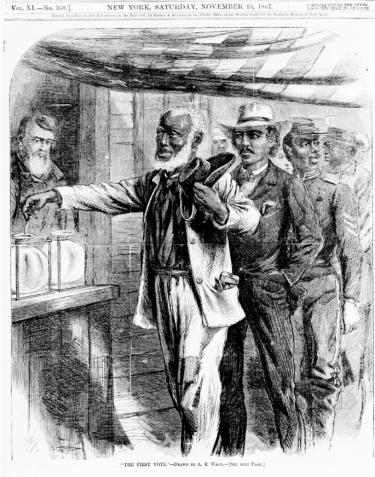

“Jim Crow Laws” purposefully limited African Americans’ ability to engage with the political and public spaces. The laws were passed with more frequency once Southern jurisdictions limited African American participation in local and national elections. In the 1880s, literacy tests became a requirement to vote and to register to vote in many Southern districts. While the Freedmen’s Bureau and local charities attempted to bring education to rural and poor communities of color in the South, many inhabitants were still unable to pass these literary tests. To help less-educated white voters, “Grandfather Clauses” were established. If a citizen could prove that their grandfather was registered to vote, then they could register to vote regardless of if they could pass the literacy test. Since many African American’s grandfathers were slaves, and consequently unable to vote, then they could not utilize this loophole. Because of literacy tests, and other restrictions, Black voters in Southern states decreased. From 1896-1904, there were no registered Black voters in North Carolina. With little to no representation in the polling booths, African Americans were slowly losing representation in local and national politics. Without African Americans in local politics, the stage was set for restrictive laws on African Americans to pass with little opposition.

A major characteristic of the Jim Crow Era was segregated public amenities justified under the idea of “separate, but equal,” such as schools and hospitals. The 14th Amendment guaranteed “equal protection” under the law regardless of race and many lawyers reasoned that if these segregated accommodations were “equal” than they were also constitutional. This argument was codified in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court Case of 1896. In 1892, Homer Plessy, a mixed-race resident of New Orleans, boarded a train in Louisiana, told the conductor that he was African American, and refused to disembark from the “White Only” car. He was arrested for violating the “Separate Car Act,” which established that white and non-white individuals must ride in separate cars. Plessy was a part of The Comité des Citoyens (“The Citizens Committee” in French) that was created to protest this Act. In Louisiana Court, the Comité argued that the Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments because it did not give equal treatment to African Americans and white individuals under the law. Louisiana ruled that the state had the right to regulate railroad companies within state borders. After the ruling, the Citizens Committee petitioned the Supreme Court to hear the case.

In a now-infamous case, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy in a 7-1 decision. The majority opinion, written by Justice Henry Billings Brown, stated that the Separate Car Act did not violate either amendment. Brown stated that the 13th Amendment was not violated because it only covered basic legal provisions to ensure that African Americans could not be enslaved again. The 14th amendment, he noted, only gave legal equality to all races and could not stop social or legal discrimination of a specific race. Any state, Brown continued, could exercise laws that separated people based on race if it was “reasonable.” The court also gave legal precedent for the states to self-regulate what was “reasonable” or not. Since many African Americans were barred from voting for their political leaders or running themselves, they could not properly prosecute “unreasonable” conditions and many of these facilities were not “equal.” This decision was not overturned until the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954 and Plessy v. Ferguson allowed legal segregation for the next five decades.

Violence was also utilized to control and recreate pre-Civil War social structures instigated by white supremacist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). On December 24, 1865, six former-Confederate commanders banded together to create a white-supremacist fraternal group. The group’s goal was to weaken African Americans’ political power and to recreate the stratified social structure that existed before the Civil War. A common control tactic was publicly lynching African Americans. Mobs attacked African Americans that were accused of a crime, formally or informally, and publicly hanged them without a trial or due process of the law. Between 1882-1968, there were 4,743 recorded lynchings in the United States. With the fear of violence, few African Americas fought racist laws or racial social hierarchies. Due to internal conflicts, the Klan lost followers in 1871 but was reenergized in 1915 with the debut of the movie The Birth of a Nation. This movie glorified Klansmen, Confederate commanders, and white supremacy while demonizing African Americans. The second iteration of the Klan continued into the 1940s and then faded again. A third iteration began in the 1950s and continues today.

The Jim Crow Era began to falter and decline after WWII. During WWII, in order to combat labor shortages during the war, war industries were desegregated with the Fair Employment Act of 1941. In the ‘50s, school districts that had been segregated since the Civil War began to win court cases for integration. School districts that were unable to win cases began to petition the Supreme Court, such as with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) Supreme Court case. This case was an amalgamation of several school integration cases throughout the county. Unlike the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, the Supreme court unanimously ruled that “separate, but equal” was unconstitutional and that the segregation of public schools, and other public spaces, violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments.

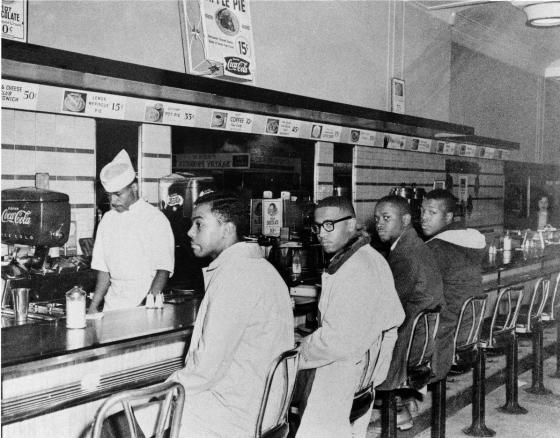

The Civil Rights Era of the 1950s and 60s protested Jim Crow Laws and regulations. For example, the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott protested the policy that African Americans needed to relinquish their seats to white riders and sit in the back of the bus. After Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to relinquish her seat to a white bus rider, residents of Montgomery, Alabama boycotted the bus system for 381 days. They withstood assaults from white citizens and the local KKK group until the buses were integrated. Also, 1960 Greensboro sit-ins protested the segregation of lunch counters by sitting at the segregated F. W. Woolworth Company amongst great backlashes. Three years later between 200,000 and 300,000 participants came to Washington D.C. for the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” to advocate for the civil and economic rights of African Americans. Throughout this era, organizations and individuals worked tirelessly to reverse the discriminatory laws of the Jim Crow Era.

The Jim Crow Era ended in 1965. This end was prompted by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or natural origin, such as discrimination in employment, in public accommodations, and voter registration. This act, while initially weak, gave the legal backing to file claims of discrimination that could be won by minority prosecutors. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, gave more legal backing to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments by prohibiting state and local government from creating voting laws that unduly discriminate against minorities. This legislation forced local governments to remove unnecessarily hard literacy tests and landowning restrictions. While racial discrimination existed after these two acts, both helped usher in more accountability to discriminating legislations. Today, activists continue working to dismantle the legacy of these Jim Crow Laws in the political and social spheres.

Further Reading

- Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation By: Ira Berlin, Marc Favreau, Steven F. Miller

- American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era By: David Blight

- Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory By: David Blight

-

Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South By: William Henry Chafe, Raymond Gavins, Robert Korstad

- Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction By: Eric Foner

- Understanding Jim Crow By: David Pilgram

Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South By: William Henry Chafe, Raymond Gavins, Robert Korstad