In May, 1787, delegates from the Thirteen Colonies met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to discuss the Articles of Confederation. Written during the Revolutionary War, these ruling guidelines were proving to be ineffective during peacetime. Without the ability to levy taxes or make decisions without the consent of the states, the national government couldn’t raise funds to pay military debts or make treaties with foreign nations. Delegates worried that the hard-fought freedom that the United States had spent eight years earning could fall apart without an immediate, drastic change to the Articles. The Philadelphia Convention of 1787, also known as the Constitution Convention, originally aimed to simply rewrite the Confederation. However, it became apparent that a completely new system was required. During this time, the Constitution began to take form and, with-it, discussion on how to protect the individual liberties of the people while creating an effective federal government. Many worried that the Constitution was not going far enough to spell out the freedoms that the citizens of the United States were entitled to. Amendments began to be proposed and the idea of a national “Bill of Rights” began to form.

The Constitution Convention led to an ideological split between those that opposed the Constitution and those that approved of it. The Anti-Federalists believed that the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government and took away power from the states. While many Anti-Federalists agreed that the Articles of Confederation were ineffective, they argued that the Constitution made the federal government too overreaching. For example, they believed that the new “president” role, the leader of the executive branch, could consolidate too much power under the constitution. This figure could then become “King-like” and forcibly convert the government into a pseudo-monarchy. Because of these worries, many Anti-Federalists called for a means to codify individual rights. In contrast, the Federalists supported the Constitution and wanted a stronger federal government. Federalists believed that the Constitution already ensured individual rights to the citizens and the creation of a “Bill of Rights” was unnecessary. To one extreme, Federalists believed their admission could set a dangerous precedent: if an individual right was not mentioned in the Bill of Rights than that omission could set a precedent that the individual did not have that right. Neither side wanted to limit individual rights, but they argued on how best to protect those individual rights for United States citizens.

On September 17, 1787, the Constitution Convention adjourned and the Constitution was sent to the states to be discussed, edited, and ratified. Between December 1787 and January 1788, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut ratified the Constitution with only minor edits. In contrast, the Massachusetts delegation erupted into fistfights as they debated and discussed the Constitution. Anti-Federalist delegates Samuel Adams and John Hancock eventually found a compromise with the proposal that the Constitution be ratified with, and only with, a caveat that amendments could be added to the Constitution. With this caveat, Massachusetts ratified the Constitution on February 6, 1788. Virginia and New York, learning of this compromise, ratified the Constitution in the same manner. By June 1788, nine states had ratified the Constitution. With this super-majority, the Articles of Confederation stipulated that the new Constitution could come into effect the following year. On March 4, 1789, the Constitution became law backed by eleven of the thirteen states. (Note: North Carolina and Rhode Island refused to ratify the Constitution until a Bill of Rights was officially added to the Constitution).

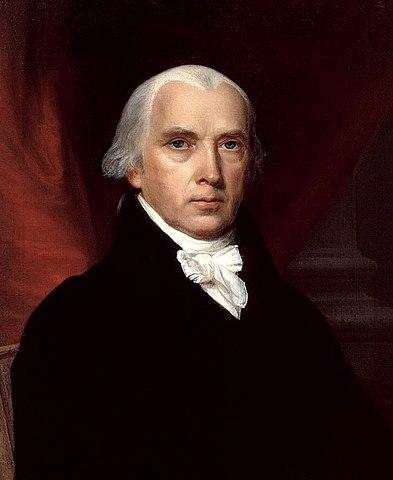

One of the first orders of business for the first United States Congress was to create and implement these additional amendments. In anticipation of this task, James Madison, a Virginian delegate, had already begun drafting these new amendments. Madison was a strong supporter of the Constitution. Between October 1787 and May 1788, Madison, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton had collaborated to write a series of essays defending the United States Constitution. Madison contributed twenty-nine of the eighty-five essays published. By introducing written amendments immediately to Congress, he hoped to capitalize on the Anti-federalists and Federalists compromise and ensure that the Constitution survived the ideological fission between the two parties. He proposed nine changes to the Constitution and introductory remarks to preface the Constitution. These additions were to be interspersed into the body of the Constitution, as opposed to being affixed at the end, and the preface was to reiterate the Constitution’s mission to protect and uphold individual rights. He used State Constitutions as a guide in creating this list of additions.

Madison’s amendments were given to a committee on June 8, 1789 to discuss and edit before they were presented to Congress as a whole. In that committee, Madison’s original list was heavily edited. The preamble was largely scratched and his changes were edited until they encompassed seventeen amendments that the committee recommended being affixed to the end of the document. On July 21, 1789, these changes were presented to Congress to be examined, discussed, and edited. After months of discussion, and rewriting, Congress sent twelve amendments to be ratified by the States. Two years later, ten of the twelve amendments had enough states to be ratified nationally. The ten amendments became what we know today as the “Bill of Rights.” These rights give American citizens codified individual freedoms, such as freedom of speech and the press. To rectify the Federalists’ worries that the omission of certain rights could cause citizens to lose rights, Congress included the ability to add amendments to the Constitution. Since the Bill of Rights was ratified, seventeen more amendments have been approved and added to the Constitution. Such as the Reconstruction Amendments that were added following the American Civil War that granted African-Americans citizenship and the right to vote. These Bill of Rights, and the discussions surrounding, gave Americans innate individual rights established by Congress and the ability to codify more as the United States changes and grows over time.