Marbury v. Madison

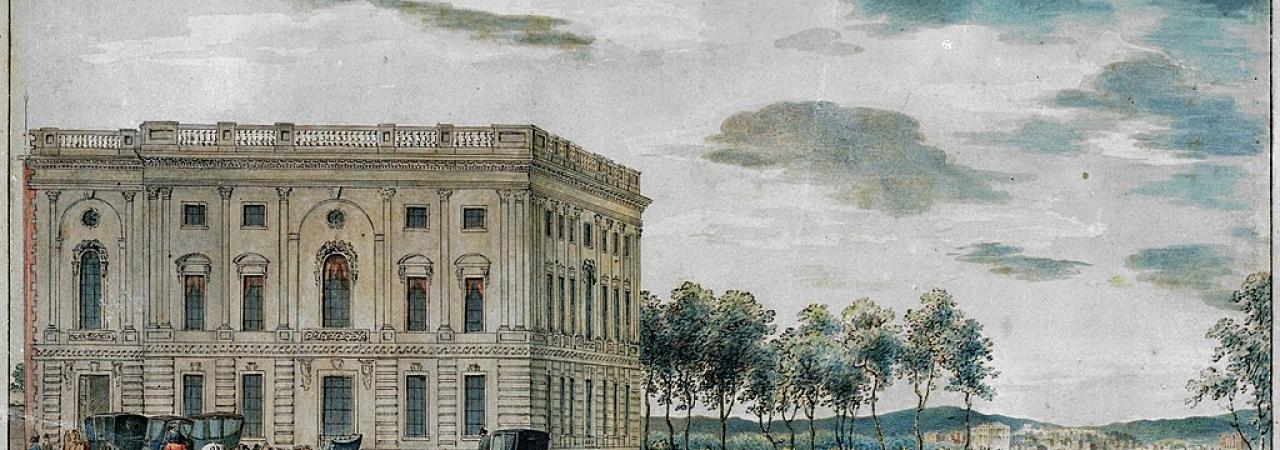

The U.S. Capitol as it appear c. 1800; the Supreme Court met in the Capitol Building until the 20th Century.

In 1803, a Supreme Court decision in the case Marbury v. Madison established the precedent for the court to decide the constitutionality of the actions of the legislature and executive branches of the United States government. It established the precedent of judicial review, expanding the power of the Supreme Court and helping to maintain the checks and balances of government; however, judicial review and its boundaries remains a debated power to this day.

The dispute that began the case started in 1801. President John Adams was on his way out of the White House, having finished his term as president and not won a reelection. During his “lame duck session” (the time between his lost election and departure from office), the Federalist-controlled Congress created 16 circuit judgeships; Adams went ahead and filled the judicial positions with Federalists in an effort to keep political control for his party and to undercut the legislative and executive power that the Democratic-Republican Party was about to gain when Thomas Jefferson became president and the new Congress was seated. One of the last appointees, William Marbury was a Federalist leader in Maryland. Due to the lateness of his appointment, Adams left office before Marbury received his signed commission as justice.

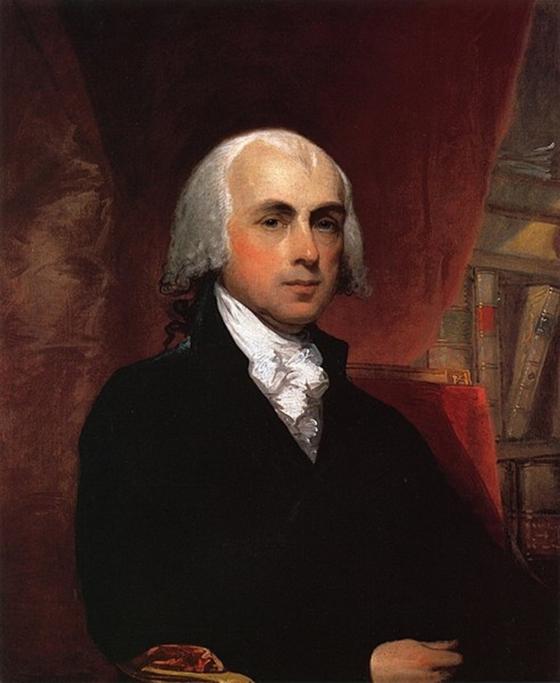

After becoming president, Thomas Jefferson told his secretary of state, James Madison, to not deliver the commission. Marbury sent a petition to the Supreme Court, asking for a writ of mandamus which would force Madison to deliver his commission that Adams had prepared. Though Marbury and his lawyer Charles Lee knew that the delivery of the commission was just formality, Marbury could not hold the office or perform the duties without the paper Adams had signed. The Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, agreed to hear the case during February 1803.

Definition: Writ of Mandamus - an order from a court to an inferior government official ordering the government official to properly fulfill their official duties or correct an abuse of discretion.

By that time, Marbury’s appointed and desired term was almost halfway over, and many political leaders felt that the case had little worth pursuing. However, John Marshall saw an opportunity to set a precedent for judicial review and secure the Supreme Court’s role in interpreting the Constitution. If the court issued the requested writ of mandamus, the court also had no power to force Jefferson or Madison to give Marbury his commission. Still, if the court did not issue the writ, the judicial branch of government would appear weak and not holding the executive branch accountable. Instead, Marshall took a different option altogether, declaring, “A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.” Though the Constitution did not give the Supreme Court the power to declare a law unconstitutional, Marshall did just that, believing this power would give the Supreme Court equal power with the legislative and executive branches and the ability to contribute to the checks and balances system.

To justify the decision, Marshall presented reasoning on the case, asking:

- Did Marbury have a right to his commission?

- If so and if his right had been violated, did a law provide Marbury a remedy?

- If so, was the correct remedy a write of mandamus from the Supreme Court?

Marshall argued that the commission was valid, since Adams had signed it while still president and forwarded it for the secretary of state’s seal. He argued it was not the secretary of state’s role to decide to invalidate the president’s choice and signature; the secretary of state was simply supposed to carry out the action and follow the law. Marshall made it clear that he was not reviewing the political decision, rather the execution of the political decision; in other words, Marshall did not review Adam’s choice of Marbury, but he did review Madison’s choice to not deliver the commission as he was supposed to by law.

Next, Marshall addressed the second question, determining that Madison’s refusal to deliver a commission which Marbury had a right to was a violation of Marbury’s right “for which the laws of his country afford him a remedy.”

Finally, for the third question, Marshall answered that the Supreme Court had no power to issue the requested writ because the provision of the act was unconstitutional. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789 (passed by Congress), the Supreme Court had the power to issue a writ of mandamus in original, but not appellate jurisdiction. Meaning, a congressional act allowed the Supreme Court to give Marbury what he wanted. However, Marshall argued that the section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that allowed for writ of mandamus was unconstitutional because it went against Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution. Marshall declined to give the writ of mandamus, but declined by declaring that the law that allowed it went against the Constitution.

With this decision, Marshall gave precedent for judicial review: that the Supreme Court could declare a law unconstitutional and thereby made the court an interpreter of the Constitution. Marbury did not get what he wanted, but Jefferson and Madison got scolded by the court, and ultimately the Supreme Court was the victor in the moment with its new precedent and powers.

It was not until 1857 and the Dred Scott decision that the Court declared another law unconstitutional. Marbury v Madison established judicial review for laws, a precedent that remains to this day though not always loved or well-accepted. Marshall’s opinion written in the case remains one of the foundational documents of U.S. constitutional studies and law.