Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—the city that welcomed the delegates to the Grand Convention in the spring of 1787—already had a long history, diverse population and messy roads. Here, over a sweltering summer, 55 delegates from all states, except Rhode Island, met formally in the State House (Independence Hall), dined and found compromises in the city’s taverns and celebrated the Fourth of July and later the success of their convention. What was it like that “Summer of the Constitution” in Philadelphia?

Muddy roads brought the delegates to town. Everyone was supposed to arrive by May 14, 1787, but spring rains slowed many of the men on their journey, and the convention did not convene until May 25. James Madison anxiously arrived on May 3 and returned to his favorite lodgings in the city, since he had spent time there at the Continental Congress. On May 13, George Washington arrived in his carriage, and the local Light Horse Troop escorted him into the city while people lined the streets to see him. Other delegates arrived sporadically, some recognized and welcomed, others arriving quietly. One of the most notable delegates—Benjamin Franklin—lived just a short walk from the State House, but due to ill health he had himself carried in a street chair to the convention when it assembled each day.

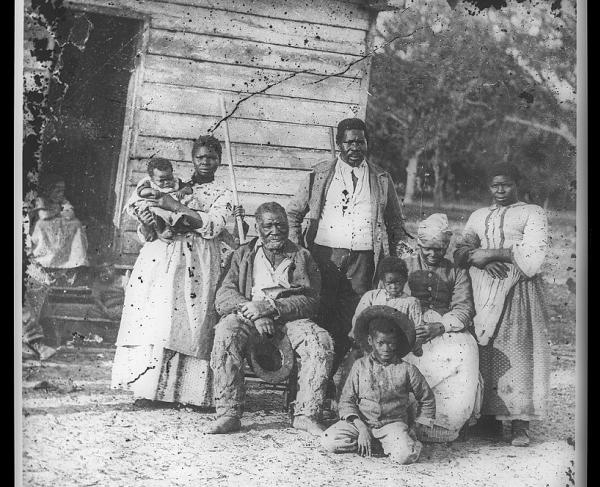

The City of Philadelphia had a population of approximately 40,000 in 1787—men, women and children, free and enslaved, Native Americans, immigrants and American-born, and representing many different religious faiths. About 6,500 houses crowded along the streets and 415 shops and stores offered goods from the state and abroad. The nearby Delaware Riverfront docked ships carrying cargoes from around the world; the docks were also the scenes of human trafficking through the Transatlantic Slave Trade which had not yet been ended along the United States’ shores. Beyond the waterfront, the main thoroughfare in town was Market Street, which included the stalls of fishmongers and butchers. Among the hurrying people of the city, wild dogs scampered, pigs rooted in the streets and dead horses decomposed on the town common. The smells, especially in the rising summer heat, must have been indescribable particularly to delegates from country farms, plantations or small villages. Contaminated water threatened everyone’s health and made alcoholic beverages in the city’s taverns a near necessity for drinks.

American culture improved in the city. The largest public library in the United States had begun as Benjamin Franklin’s project in 1731 and by the 1780s was recognized as the Library Company of Philadelphia. Charles Wilson Peale had founded the Repository for Natural Curiosities, better known as “Peale’s Museum” which displayed his art along with mastodon fossils and taxidermy animals. The College of Philadelphia with its classical approach to education was operating—another institution that Franklin supported.

As the delegates for the anticipated convention arrived, most of the fifty-five men found lodgings in the taverns and respectable boarding houses near the statehouse. Mrs. Mary House and her daughter Eliza Trist ran House’s Boarding House at the corner of Fifth and Market Streets. Other delegates joined Madison here, including Edmund Randolph, James McHenry, John Dickinson, George Reed and Charles Pinckney. Miss Daley’s Boarding House became the temporary residence for Alexander Hamilton and Elbridge Gerry while Mrs. Marshall’s lodged Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth. George Mason from Virginia stayed at the Indian Queen, the largest tavern in the city, and reported that he was charged “twenty-five Pennsylvania currency per day, including our servants and horses, exclusive of club in liquors and extra charges.”

Some delegates stayed with friends in private homes. Robert Morris pressed George Washington to reside with him in his large family home. The spacious mansion, walled gardens, icehouse, hothouse and large stable were located not far from Franklin’s home, giving the Virginian and Pennsylvanian statesmen the opportunity to meet soon after Washington’s arrival.

Taverns offered lodging and also dining rooms and hearty meals for the delegates as they arrived and stayed the summer for the convention. Indian Queen was the largest tavern, but City Tavern, Epple’s and Oeller’s also did brisk business. Edward Moyston, the owner of City Tavern, anticipated the convention and arranged newspaper advertisements boasting that he “provided himself with cooks of experience, both in the French and English taste” and inviting the delegates to sample and drink the fine liquors he had already stocked for their pleasure. Once the convention was in session, delegates ate their large midday meals at the taverns and often met in “clubs” in the taverns for supper in the evening. These meals and organized “clubs” allowed the delegates to informally discuss, compromise or regain respect for each other after the heated debates in the State House.

The State House was already historic—the location where the Second Continental Congress had convened in 1775, where George Washington had been appointed general of the Continental Army and where the Declaration of Independence had been signed. The Confederation Congress had met at the State House, but by 1787 was meeting in New York City’s Hall when in session. Many delegates and local residents remembered their Revolutionary War experiences. Here, ten years prior in 1777, the Philadelphia Campaign had forced the Continental Congress to flee the city, the British captured it and George Washington and his army wintered in the countryside at Valley Forge. Now, with American Independence secured and the need to find a better system of government, the delegates walked through the historic doors once again.

As the convention opened officially on May 25, the delegates worked through the formalities. They agreed on secrecy so their discussion would not be influenced by popular opinion or response. To prevent eavesdropper, the windows of the State House were nailed shut—making stifling summer heat even more miserable inside.

On the Fourth of July 1787—just 11 years after the Declaration of Independence had been approved at that very location—the delegates took a break for the occasion. The Light Horse Brigade paraded with other local militia, a solemn church service was held at the German Lutheran Church (Washington attended), toasts were made in the taverns, speeches echoed in the streets and rooms, and “a very beautiful set of fire works” ended the day. One hopeful observer noted, “Methinks, I already see the stately fabric of a free and vigorous government rising out of the wisdom of the Federal Convention.”

Another notable celebration took place on September 14 when the First Troop of the City Light Horse hosted a party for George Washington at the City Tavern. Other delegates also attended. When the party ended, the bill included 54 bottles of Madeira, 60 bottles of claret, 50 bottles of “old stock” along with porter, beer, cider and bowls of rum punch and an addendum for “breakage.” Undoubtedly, it had been an evening of good fun, war memories and optimism for the future.

The result of the gathered delegates and the discussions in Philadelphia that summer was the drafted Constitution of the United States. Signed on September 17, 1787, and prepared to be sent to Confederation Congress and then to the states for ratification, the document would become the law of the land, if approved and ratified. Far from the crowded, smelly streets and welcoming taverns, away from the stifling room in the State House and the bustling rumors, the people of the United States pondered and debated the document forged in Philadelphia. The long summer in Philadelphia was over, but the work of forming and preserving “a more perfect union” had just begun.