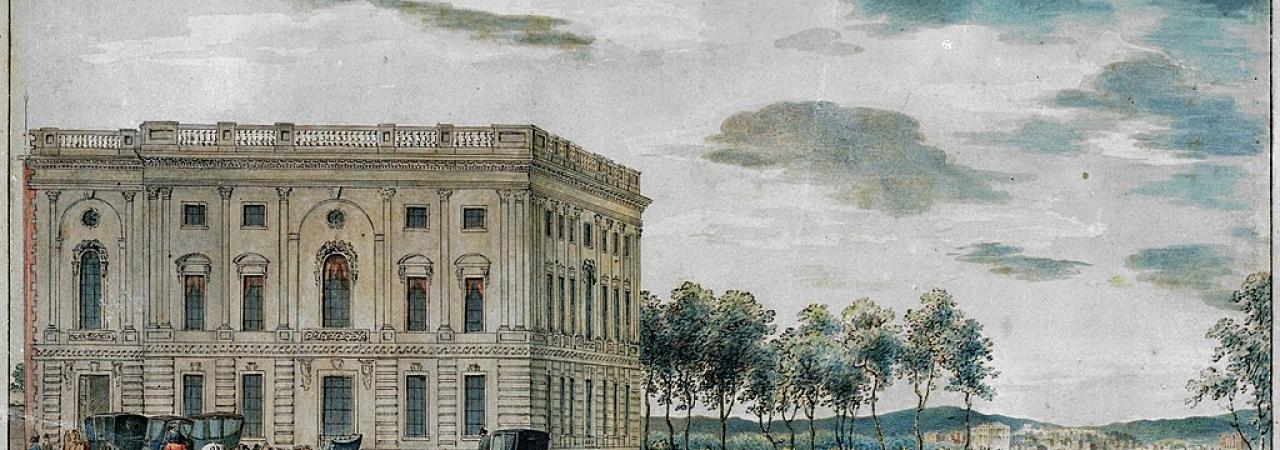

The U.S. Capitol as it appear c. 1800; the Supreme Court met in the Capitol Building until the 20th Century.

He served 34 years—still the longest serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He shaped the power of the judicial branch in the United States system of government and in the check and balances. He set the precedent for judicial review and foundations of constitutional law. John Marshall, 4th Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, made history and shaped the first three decades of the 19th Century in the United States. The "Marshall Court" refers to the Supreme Court between the years 1801 and 1834 when John Marshall was the Chief Justice.

Born in 1755 in Virginia, John Marshall served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Toward the end of the conflict, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, beginning his political career. Marshall supported the ratification of the Constitution in the late 1780s and helped his home state endorse that document. During John Adam’s presidency, Marshall went to France to try negotiate freedom for American shipping and commerce, leading to the XYZ Affair. Marshall became the congressional leader of the Federalist Party when he returned to the United States and then was appointed secretary of state in 1800 after cabinet changes during the Adams administration. The following year, 1801, as his administration came to an end, John Adams appointed John Marshall to the Supreme Court.

Anti-Federalists and Democratic-Republicans believed that Adams had stacked the federal courts as he departed from the presidency. Marshall was one of the judges they scrutinized since he had been a Federalist Party leader, but Marshall surprised many in the next decades with his decisions that rose above politics and expanded the power of the Supreme Court for judicial review and interpreting the Constitution.

Sworn into office on February 4, 1801, John Marshall served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court until his death on July 6, 1835. He was known for his dedication to his position and also for the personal ways he worked with the other justices. Under his leadership, the court began issuing a majority opinion and toward the end of Marshall’s tenure, he began requiring the opinions to be written, instead of just delivered orally. Many recognized the dignity that he restored to the Supreme Court and the precedents that he set, bringing the court into the 19th Century and establishing it in the balance of governmental power and checks and balances.

The Marshall Court—as the Supreme Court was often called during John Marshall’s tenure—stared with six Justices, but Congress eventually added a seventh seat. Presidents from Thomas Jefferson to Andrew Jackson appointed justices while Marshall was Chief Justice. The court’s decisions in this period laid important precedents and some of the most impactful decisions include:

Marbury v. Madison: In 1803, Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion on this case led to the overturning of a portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789, declaring it unconstitutional and establishing the practice of judicial review.

Fletcher v. Peck: Marshall’s written opinion in this 1810 case resulted in the court striking down a state law as unconstitutional.

Martin v. Hunter's Lessee: Justice Story’s opinion in this 1817 case ruled that the Supreme Court held appellate power over state courts in matters regarding the U.S. Constitution, federal laws and federal treaties.

McCulloch v. Maryland: Chief Justice Marshall wrote the unanimous opinion for this case, ruling that Maryland did not have the power to tax a federal bank operating in its state. This 1819 decision broadly interpreted the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution and supported Congress in the establishment of a national bank.

Dartmouth College v. Woodward: With this 1819 decision, the Supreme Court ended and invalidated New Hampshire’s efforts to change Dartmouth College’s charter, using the Contract Clause to protect corporation’s contracts from state interference.

Johnson v. McIntosh: Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in this 1823 case clarified and confirmed that private parties were not allowed to purchase land from Native Americans—rather it was supposed to be handled by the federal government through treaties.

Gibbons v. Ogden: This case in 1824 led to the court’s decisions—led by Chief Justice Marshall—to strike down a New York law that had granted a steamship monopoly in that state, thereby upholding that Congress would regulate commerce.

Worcester v. Georgia: This 1832 decision canceled Georgia’s conviction of Samuel Worcester and affirmed that states did not have authority to deal with Native American tribes or nations. (President Andrew Jackson did not enforce the court’s decision and Georgia continue to interfere in Cherokee tribal affairs.)

Barron v. Baltimore: Chief Justice Marshall wrote the unanimous opinion this 1832 case, holding that the Bill of Rights did not apply to the actions of state governments. (This decision would later be overruled by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution and later court decisions.)

When John Marshall died on July 6, 1835, he had served as Chief Justice for just over 34 years. Roger B. Taney succeeded him.