Naval Operations in Charleston Harbor

At the outset of the Civil War in April, 1861, the Abraham Lincoln administration faced military challenges ashore and afloat. The regular U. S. Army, mustering around 16,000 men, was not large enough and was too spread out across the states and territories to mount a campaign against Richmond. On April 15, two days after the fall of Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 new soldiers to suppress the rebelling states. Similarly, the U. S. Navy that April could count only 42 commissioned warships, spread from Boston to Pensacola and stationed overseas. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles ordered a crash shipbuilding and acquisition program, and on May 3, Lincoln issued a call for 18,000 new sailors to take the war to sea.

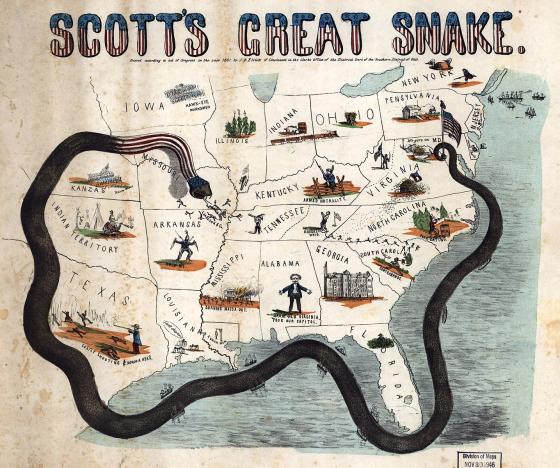

By mid-1861, the Navy had four missions. First, warships were needed to support the new blockade of Southern ports. Union war plans included crippling the Confederacy’s economy by strangling its export of cotton, tobacco, and other cash crops. Second, shallow-draft vessels were needed on the inland rivers, particularly the Mississippi and its tributaries, to support army operations. Third, Union warships were tasked with destroying Confederate commerce raiders on the high seas. And fourth, Union squadrons were charged with closing port cities and reducing coastal defenses. For much of 1862 and into 1865, this last type of operation was conducted along the coast of South Carolina, centering on the port city of Charleston.

Charleston was the second-largest city in the Confederacy after New Orleans. It boasted a large natural harbor, formed by the Cooper and Ashley rivers. Piers and docks stretched along the city’s two-mile waterfront. A handful of low islands surrounded by tidal swamps lined both sides of the harbor entrance. Unlike the other big Confederate ports at New Orleans and Wilmington located several miles up narrow rivers from the coasts, Charleston was only three miles from the Atlantic. Its political significance as the “cradle of secession” and the scene of the opening shots of the war made closing the port at Charleston a priority for the U. S. Navy. As the first year of the war progressed and the Navy constructed a larger fleet that could conduct sustained offensive operations, Confederate troops in Charleston built up the defenses of the city.

Soon, a ring of forts and heavy gun batteries surrounded Charleston Harbor. Covering the northern side of the main ship channel on Sullivan’s Island, Fort Moultrie dated to the British invasion of the city in 1776. By 1862, the fort centered a crescent of gun emplacements facing south across the channel and east out to sea. Inside the harbor, Castle Pinckney on another small island was only a few thousand yards from the Charleston docks. In the city itself, several large guns were mounted on the waterfront and covered the approaches to the Cooper and Ashley rivers. Further south, several batteries were mounted on James Island, including Fort Johnson, which had fired the first shot of the war. Guns were placed on Morris Island along the coast, where Fort Wagner was built on the beach facing north and east. Finally, in the center of the harbor, the Confederates garrisoned the newly-acquired Fort Sumter, whose guns commanded the harbor entrance.

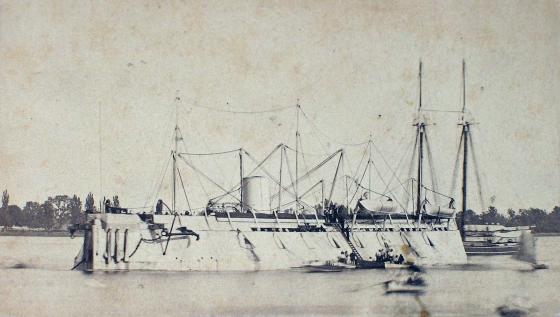

Charleston had been blockaded by Union warships since July 1861. The city’s proximity to Bermuda and Nassau made it a primary port for Southern blockade runners. Although inefficient at first, the blockade grew more effective in 1862 and the Confederates looked for the means to act against the Union warships. The successful attack of the ironclad CSS Virginia against two Union warships in Hampton Roads in April showed Confederate shipbuilders the advantages of iron versus wooden warships. By the end of September 1862, the Confederates had launched two ironclads from Charleston, similar in configuration to the CSS Virginia but somewhat smaller. Named the CSS Chicora and the CSS Palmetto State, the two ironclads operating together against the Union fleet seemed a powerful threat.

Both ironclads sortied out of Charleston Harbor in the pre-dawn hours of January 31, 1863, and approached the Union warships in the darkness. The Palmetto State struck first, plowing her underwater ram into the steam gunboat USS Mercedita. The ironclad fired at the wooden ship as it heeled over, disabling her engine and tearing a hole in her hull. Taking on water and unable to maneuver, the Mercedita’s captain surrendered his vessel. Thirty minutes later, the Chicoraattacked the sidewheel steamer USS Keystone State and traded broadsides with the Union vessel. Keystone State was hit several times; her engine also damaged by shellfire. Barely able to maneuver, Keystone State limped away from the fight. Four other Union warships came to the scene but were unable to damage the Confederate ironclads which retreated to Charleston. The Union ships suffered 47 casualties, including 20 dead. The attack by the ironclads caused chaos in the blockading fleet but the blockade itself was not broken. Since they had nearly destroyed two wooden gunboats, the continued presence of Palmetto State and Chicora ensured that any future Union assault on Charleston would include new, heavily armored ironclad monitors, named for the turreted warship USS Monitor that had fought the Virginia to a draw.

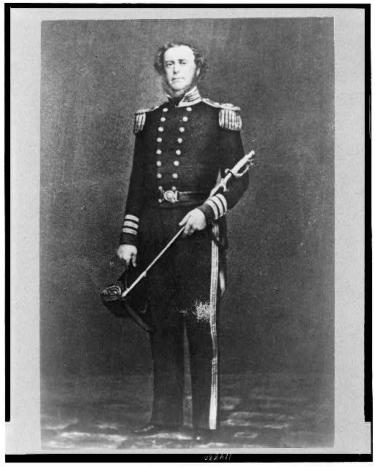

Commanding the U. S. Navy squadron at Charleston was Rear Admiral Samuel F. DuPont. DuPont was pressured by Lincoln and Welles to move against the Charleston defenses. By early April 1863, seven new monitors had arrived at Charleston and were added to the USS New Ironsides, an ironclad steamer with 16 broadside guns, and the ironclad USS Keokuk. At noon on April 7, the nine vessels steamed in a column toward the harbor. The leading monitors got caught up in obstructions blocking the channel between Fort Sumter and Sullivan’s Island and the formation quickly fell apart. The strong, swirling currents pushed some of the Union warships into each other. New Ironsides, DuPont’s flagship, was struck over 50 times and the monitors also took a beating. Although their gun turrets were armored, the monitors’ decks and machinery were vulnerable; several suffered jammed turrets or broken gun port covers. The Keokuk sank the next morning after being hit 90 times in 30 minutes. DuPont learned the hard way that the revolutionary new vessels were no match for large numbers of shore artillery. The two-gunned monitors were outmatched by the forts; DuPont’s ironclads fired only 151 rounds compared to 2,209 rounds fired from Confederate guns.

As they had in Hampton Roads with the Virginia, the Confederates looked to innovative technology to sink the Union fleet outside Charleston. By late 1863, blockade running traffic had slowed to nearly nothing. Early that August, the Confederates launched a small, wooden schooner with a low profile named the Torch. No guns or masts were mounted on the vessel, but three 100-pound torpedoes (or mines) were carried on spars attached to the bow. Torch used a small steam engine for propulsion. On the night of August 20, the Torch slipped out of the harbor and approached the USS New Ironsides. Unnoticed until 40 yards away, Torch had difficulty maneuvering when her engine suddenly lost power and her crew were unable to place the charges next to the Union vessel. Now alert, the New Ironsides crew could not depress her guns far enough to target the small craft. After nearly getting her torpedoes hung up on the big ironclad’s anchor chain, Torch’s crew got her engine running and she escaped back to Charleston in the darkness.

The Confederates tried again. That fall, they launched the CSS David, an improved Torch design which, after testing, was accepted by the Confederate Navy. With a larger engine and a 50-foot long, robust wooden hull, the David could be partially submerged by ballast. She carried a 70-pound spar-mounted torpedo forward and steel plate was added to her upper deck and smokestack. On the night of October 5, 1863, the David steamed past Fort Sumter and again approached the New Ironsides. To confuse the crew and buy more time to attack and escape, David’s captain hoped to first disable the ironclad’s officer of the deck with small arms fire. As the torpedo boat approached the ironclad, David’s pilot mortally wounded the New Ironsides officer with a shotgun blast. As the ironclad’s crew regrouped, David’s torpedo exploded alongside. New Ironsides and the David both reeled from the blast. David’s engine was swamped by the geyser of water and her crew came under rifle fire from the New Ironsides. David’s crew, shaken and wet but unharmed, restarted the engine and motored back to Charleston. The New Ironsides was more heavily damaged and required drydocking in Philadelphia. The big ironclad was out of service for another year and never returned to Charleston. Five months later, the David attempted to sink the USS Memphis outside the harbor with a 95-pound torpedo. Again, the David reached her target unobserved but the charge failed to detonate after three attempts.

The successes of the Torch and the David led the Confederates to be bolder still. Since early 1862, Southern engineers had been experimenting with submersible craft. In mid-August, 1863, the most advanced of these arrived in Charleston from Mobile where it was built and tested. The H. L. Hunley was a 40-foot long, iron-hulled craft large enough for eight men inside to provide propulsion instead of relying upon a steam engine. Her armament was a bow-mounted spar torpedo with a 135-pound charge. Although Hunley accidentally sank on two test voyages in August and October, killing five crewmen the first time and all eight the second time, the vessel functioned and offered the possibility of success. On the night of February 17, 1864, Hunley slipped beneath the wave tops and approached the screw sloop-of-war USS Housatonic. Hunley was sighted a few hundred feet from the Union warship, and rifle fire pinged off her iron hull as she approached. The spar torpedo was successfully detonated against Housatonic’s hull and the big sloop sank in 15 minutes. Hunley had achieved the first successful sinking of an enemy ship by a submarine but she disappeared that evening with her third crew, never to return from her historic mission.

During the war, Union naval operations around Charleston had mixed results. The fleet succeeded in choking off blockade running vessels that could have substantively aided the Confederacy. They failed, however, in reducing the forts and batteries surrounding the harbor without the assistance of army troops on the ground. On September 7, 1863, Fort Wagner on Morris Island was evacuated after two infantry assaults and a two-month long bombardment, including over 8,000 rounds fired from the New Ironsides and the monitors. From Morris Island, Forts Moultrie and Sumter took a beating from Union army and navy guns for the rest of the war but were never captured. For the Confederates, their series of tactical victories using ironclads, torpedo boats and submarines could not forestall the strategic loss of Charleston when Union armies approached from the west. Charleston and all the remaining forts and batteries circling the harbor were evacuated February 15, 1865, and the city surrendered three days later.

Further Reading

-

War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 By: James M. McPherson

-

Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History By: Richard Snow

-

Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig Symonds

-

The Civil War at Sea By: Craig Symonds