Beginning with the reign King Louis XIV, cannons produced for the French army had a Latin motto engraved on their barrels: “Ultima Ratio Regum,” or “The Last Argument of Kings.” In the American Revolutionary War, the rebellious American colonists turned these symbols of royal power into a critical weapon in their struggle for independence.

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the British had retreated back to the city of Boston. There they found themselves surrounded and besieged by an army of armed colonists. British General John Burgoyne disparaged the colonists as “a preposterous parade” and “a rabble in arms,” but the new commander of this Continental Army saw potential. General George Washington wrote that “in a little time we shall work up these raw materials into very good stuff.” Farmers and artisans could be made into soldiers, but the colonists had very little artillery and cannons could not be summoned out of thin air.

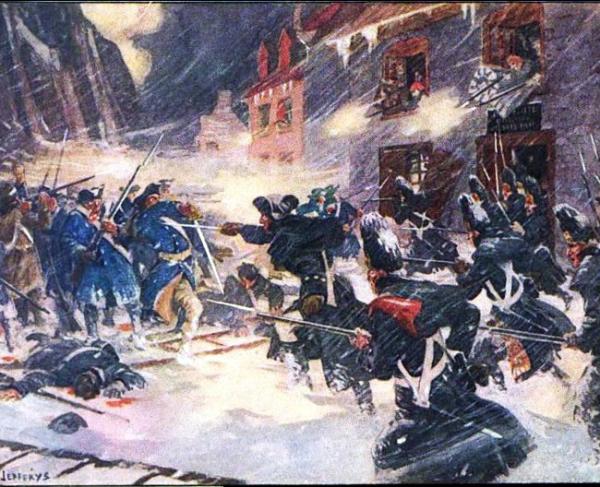

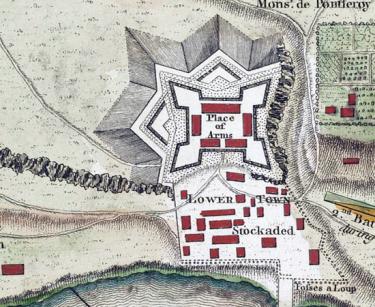

Nearly three hundred miles away, on the shore of Lake Champlain, was a treasure trove of artillery. In May of 1775, Ethan Allen led a militia made up of settlers from present-day Vermont, called the Green Mountain Boys, in a surprise attack that captured Fort Ticonderoga and its small British garrison without firing a shot. With this act of “burglarious enterprise,” as one British writer described it, the rebels took possession of two hundred cannons. Most officers thought that moving the guns all the way from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston was impossible, but Henry Knox thought otherwise.

Knox had been a bookseller before the outbreak of war, and his bookshop was known as “a fashionable morning lounge” that counted John Adams among its regular patrons. After Lexington and Concord, Knox and his wife snuck out of Boston in disguise. With a commission as a colonel in the Continental Army, Knox went to Washington and confidently predicted that once the cannons had been taken by boat from Fort Ticonderoga to the southern end of Lake George, it would take fewer than twenty days to move them overland to Boston.

Henry Knox left for Fort Ticonderoga on November 16, 1775. Once he arrived at the fort, he selected 58 pieces of artillery to take back to Boston. Most of artillery pieces were “12-pounder” or “18-pounder” cannons (depending on the weight of the cannonball they fired). Knox also brought one massive 24-pounder cannon, nicknamed “Old Sow,” that weighed more than 5,000 pounds and several high-arching mortar guns that weighed one ton each. In total, Henry Knox’s “noble train of artillery” weighed 120,000 pounds, or 60 tons.

On December 9, 1775, three boats loaded with artillery set sail on Lake George. Traveling forty miles down the ice-covered lake took eight days. Once the artillery was on the southern shore of the lake, Knox and his men used more than one-half mile of rope to secure the guns to 42 sleds. Hauling the heaviest guns required eight horses and sometimes additional oxen as well.

The journey on land required crossing the frozen Hudson River four times. The leader of each sled team carried an axe, so that if a cannon fell through the ice they could cut the lines before it dragged the horses underwater as well. Henry Knox himself nearly froze to death while trying to walk through three feet of snow in a blizzard. In a letter to Washington, he wrote that “it is not easy to conceive the difficulties we have had,” but not a single cannon was lost. Henry Knox and his noble train of artillery arrived at the Continental Army camp outside Boston in late January 1776. The journey that Knox had estimated would take sixteen or seventeen days had taken forty.

On the night of March 4, the cannons were moved into position on Dorchester Heights, overlooking the city and the harbor. On March 5, when British General William Howe learned what the colonists had done, he exclaimed that “these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.” On March 6, 1776, he gave the order to prepare for evacuation. On Saint Patrick’s Day 1776, 120 ships carried 9,000 British soldiers, 1,200 dependents, and 1,100 Loyalists out of Boston. On the deck of one ship, the merchant George Erving told other Loyalists, “Gentlemen, not one of you will ever see that place again.”

Washington Irving described Henry Knox as “one of those providential characters which spring up in emergencies as if formed by and for the occasion.” His race up the ranks proved that in this new Continental Army capable men would not be held back by their class status, unlike in the British army. Knox and his “noble train” allowed the colonists to force Britain to retreat from Boston, a crucial early victory that bolstered morale and showed that the Americans had a chance of winning the war. The actions of these people at these places still matter to us today as critical links in the chain of events which led to the creation of the United States of America. By promoting men of merit like Henry Knox, regardless of their social class, George Washington made the Continental Army an embodiment of the egalitarian ideas that the new nation would profess.

Further Reading:

- The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (The Revolution Trilogy, 1) By: Rick Atkinson

- Fort Ticonderoga: Key to a Continent By: Edward Pierce Hamilton

- Henry Knox's Noble Train: The Story of a Boston Bookseller's Heroic Expedition That Saved the American Revolution By: William Hazelgrove