Mary Young Pickersgill

In the Summer of 1813, as the War of 1812 waged across the United States, Major George Armistead wrote to General Samuel Smith:

We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy. That is to say, we are ready except that we have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.

Armistead wanted a flag that measured 30 by 42 ft in size with the “finest quality bunting” to intimidate any foreign invasion on the harbor. Commodore Joshua Barney, a subordinate of Armistead, knew just the person to make such a large and impressive flag: Mary Young Pickersgill, his sister-in-law.

Mary Young Pickersgill grew up surrounded by flags and flag makers. She was born in Philadelphia, PA, on February 12, 1776, as the Revolutionary War came underway. After her father’s death two years later, her mother, Rebecca Flower, opened a flag shop on Walnut Street in Philadelphia. She sewed ensigns, garrison flags, and the “Continental Colors” for the Continental army that passed through the city. When the family moved to Baltimore several years later, Flower opened another flag shop.

Pickersgill worked alongside her mother until she was twenty years old. On October 2, 1796, she married John Pickersgill, a merchant. The couple moved to Philadelphia for John’s work and had four children together. Pickersgill worked as a housewife and remained in the United States as John accepted a job in London to work in the British Claims Office. Unfortunately, he never returned to Pickersgill or the United States and died there on June 14, 1805.

Now a widow, Pickersgill relied on the same skills her mother had relied on after her husband’s death: flag making. She moved to Baltimore with her one surviving daughter, Carolina, and her aging mother. The family rented a house at 44 Queen Street and opened a flag shop once again. In this flag shop, Commodore Barney came to request two flags: one smaller flag that measured 17 by 25 ft and the dauntingly large flag of 30 by 42 ft that Armistead requested.

Because of the size and scope of the project, Pickersgill requested more help and a larger space. For the next six months, Pickersgill, with her mother, Rebecca Flower; her daughter, Carolina; two nieces, Eliza Young and Margaret Young; and a free African American apprentice, Grace Wisher, worked on sewing these massive flags. Several other unnamed seamstresses and African American boarders may have helped during this intense sewing process. To have enough space to work, Pickersgill rented out a local brewery and spread the fabric out on its large factory floor. After months of work, the flag was finished on August 18, 1813. The large flag cost $405.90, between $6,000 and $7,000 today, and the small one $168.54, between $2,000 and $3,000 today.

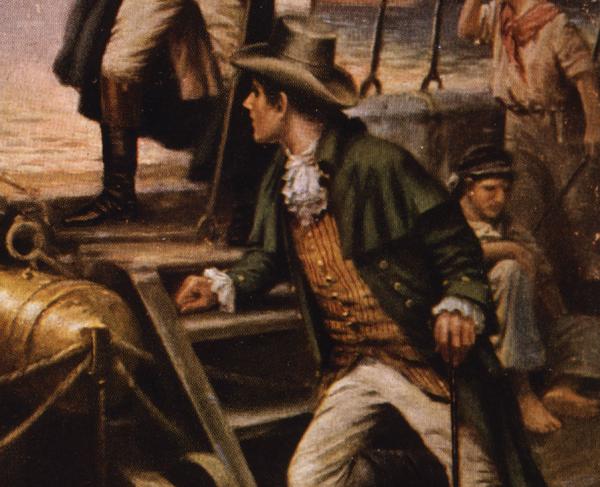

One year later, from September 12-15, 1814, British invaders attacked Baltimore Harbor. On September 13, nineteen British ships began to attack Fort McHenry with Congreve rockets and mortar shells. British ships attacked for 25 hours straight, firing between 1,500 and 1,800 cannonballs toward the defenses.

Aboard a British ship, Francis Scott Key, a local lawyer, witnessed the fight. On September 5, he had boarded the British HMS Tonnant with Colonel John Stuart Skinner to negotiate the release of Maryland physician Dr. William Beanes. Worried that their position might be compromised, the British soldiers refused to let Key, Skinner, or Beanes leave the ship. On September 14, Key witnessed the large 30 by 42 ft American flag sewn by Pickersgill raised over the still intact Fort McHenry. So inspired by the sight, Key wrote the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” Set to the music of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” the poem was published as “The Star-Spangled Banner” later that year. In 1931, this song became the National Anthem of the United States.

Pickersgill never lived long enough to see a song inspired by her flag became the national anthem or see it become an icon of the United States. Instead, she lived a quiet and prosperous life filled with philanthropy. From the proceeds of her successful flag business, Pickersgill was able to purchase her home, which is now known as the Star-Spangled Banner House. From 1828-1851, she served as president of The Impartial Female Humane Society, which helped poor Baltimore families pay for their children’s education and women find employment. While she was president, the society opened a home for “aged-women” in West Baltimore. This retirement home has since expanded to include “aged men,” moved to Townson, Maryland, and has been renamed to the Pickersgill Retirement Community. By the time of her death on October 4, 1857, she was not only the maker of the Star-Spangled Banner but a successful businesswoman and a dedicated philanthropist.