Short History of The Star Spangled Banner

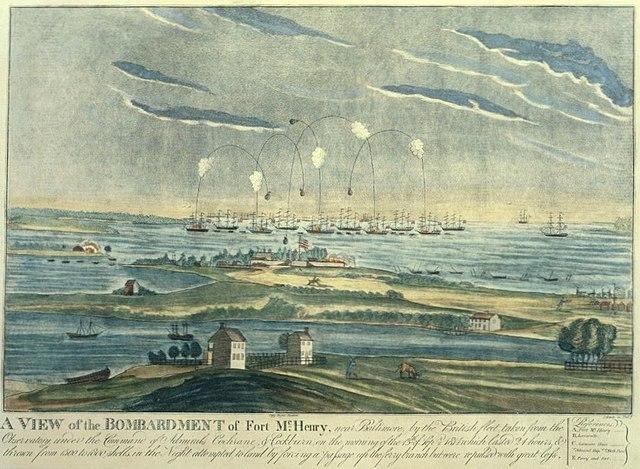

As the sun broke the horizon on September 13, 1814, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane gave the order for British naval ships to commence firing at Fort McHenry. Located in the Baltimore Harbor, Fort McHenry was one of the last lines of defense for Baltimore: if the fort was captured, then Baltimore would be as well. With Washington, D.C., burned just a month prior, the capture of Baltimore would mean that the just formed United States would lose two major coastal cities. These cities were financial and political strongholds, and, without them, Britain could claim victory for the entire war.

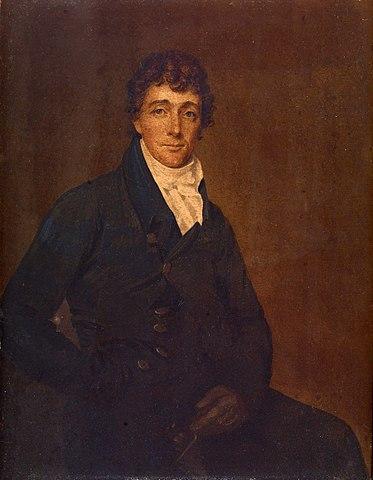

On a merchant ship in the harbor was British Prisoner Exchange Agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner and Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key. On September 5, Stuart and Key had sailed into the harbor to meet with Admiral George Cockburn to discuss the release of Dr. William Beanes. Beanes was a doctor, and a colleague of Key, who had refused to give food and drink to British soldiers who had happened upon his house in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. He was scheduled to be hanged. Stuart and Key successfully negotiated Beanes’s freedom. However, since they were by the British fleet in the harbor, and privy to the British’s positions and plans to attack Baltimore, the three men were unable to return to shore.

On September 12, the British landed their forces at North Point, a peninsula at the fork of the Patapsco River and the Chesapeake Bay to attempt a land attack on Baltimore. The British pushed on toward the city and were attacked at noon, resulting in the death of British Major General Robert Ross. Colonel Arthur Brooke took command and skirmishes continued that day. The Americans retreated to Baltimore and the British consolidated their forces.

With many American forces emerging in the night, the British decided to launch a naval attack on Fort McHenry commanded by Admiral Cochrane. Major George Armistead, a future uncle to Confederate General Lewis Armistead in the Civil War, commanded the fort. For twenty-four hours, mortar shells and Congreve rockets were hurled at the fort. Over the harbor, there was a cloud of smoke that was only illuminated by the glow of rockets.

However, the British gunners had poor aim. Because of the American cannons in the fort and previously sunken merchant ships that Armistead had commanded to ring the entrance to Baltimore harbor, the British couldn’t get close to the Fort. At nightfall, Cochrane sent 1,200 of his men to the shore in an attempt to attack the fort from the rear. American forces met the incoming soldiers and impeded them from advancing.

The next morning, Armistead raised a thirty by forty-two-foot United States Flag over the fort. Customarily, this garrison flag was raised every morning at reveille, but after a night of fighting this action took on a new meaning. The British, equally fatigued after the long fight and running low on ammunition, noted that they could not overtake the fortifications of Fort McHenry. Beanes, Key, and Stuart were sent back to the Maryland shore and the British retreated and set off for New Orleans.

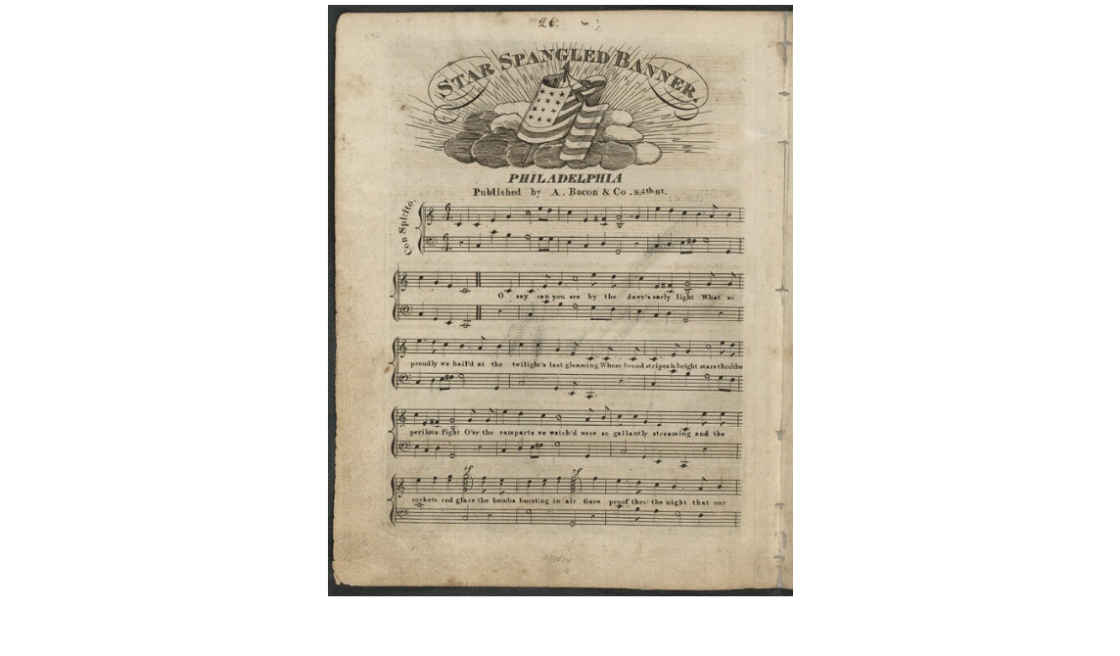

Throughout this battle, Key was in the harbor hearing cannon fire and the booms of explosives. After the hours of bombardment and the fear that the British could overtake the fort and head to Baltimore, Key awoke to a proud display of American patriotism and a symbol that they were not going to stop fighting. That morning he wrote notes for a future poem about this event. Later that week, he finished the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” On September 20, the Baltimore Patriot published “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” Francis Scott Key’s brother-in-law set the poem to music, and the combined poem and music were published under the name “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

After it was published, “The Star-Spangled Banner” became one of the many patriotic songs sung throughout the country. After 1889, it accompanied the flag raisings by the Navy. President Woodrow Wilson adopted the song as a de facto “national anthem” in 1916 but did not codify this ruling. In 1929, “House Resolution 14” was presented to Congress to name “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the official national anthem to the United States. There were many objections to this resolution.

One objection was that the tune of the “Star-Spangled Banner” was taken from the song “To Anacreon to Heaven.” This song was the theme for the Society of Anacreon, which was active between 1766-1791. The Society of Anacreon was a gentleman’s club that meet monthly to listen to music of questionable tastes and to socialize. Ralph Tomlinson wrote the lyrics and John Stafford Smith composed the melody in 1788 and 1780 respectively. The song alluded to alcohol consumption and love in the last line of the first stanza, “I’ll instruct you like me to entwine the myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s wine.” Even though only the tune was used, some members still saw it risqué that the two songs could be intertwined.

Other objections include the difficulty of the song to sing and play, the inability to dance or march to the song, and it being too military-centric. The resolution did not pass until it was reintroduced to Congress in 1930. It was officially adopted by law on March 3, 1931. Other songs that were possible contenders for the position as national anthem were “Hail, Columbia,” “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” and “America the Beautiful.”

The flag itself was sewn by Mary Young Pickersgill. Major Armistead was assigned to command Fort McHenry in June 1813. He commissioned the Baltimore-based flag-maker to sew two flags, one that is 17 by 25 ft and one that is 30 by 42 ft. The flags were so large that she sewed them with her daughter, Caroline; two nieces, Eliza Young and Margaret Young, and an indentured African American servant, Grace Wisher, on the floor of a nearby brewery. In addition, there were potentially other workers that helped with this behemoth project that have not been recorded. The larger of the two flags dwarfs the standard size of garrison flags today that measure 20 by 38 ft. As per the Second Flag Act that was ratified on January 13, 1794, there were fifteen red and white stripes and fifteen white stars in a field of blue on the flag. The additional two stripes represent Vermont and Kentucky, who entered the Union in 1791 and 1792 respectively. It wasn’t until April 4, 1818, with the Third Flag Act that the number of stripes were reduced back to thirteen and the number of stars on the flag equate to the number of states in the Union.

After the war and before his death in 1818, Major George Armistead, who was later promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, acquired the large flag. The flag was passed down within the family until Eben Appleton, Armistead’s grandson donated the flag to the Smithsonian Institute in 1912. Between Armistead’s acquisition of the flag and the Appleton’s donation, pieces of the flag had been cut off and sent to veterans, government officials, and other prominent figures. In 1914, Amelia Fowler, a flag-restorer, was hired by the Smithsonian to help stabilize the fragile flag while it was on display. Preservation was initiated again in 1981 to reduce dust on the flag and reduce the amount of light shining on the fabric. Those preservation efforts weren’t enough. In 1994, the flag was removed from the wall, so conservators could remove the linen backing that Fowler sewed and further remove harmful materials from the flag’s surface. A new climate and light-controlled exhibit were created to house the flag and discuss its history.

Francis Scott Key wrote the “Star-Spangled Banner” as a joyous poem after he was relieved that the United States had preserved against British attack. Since then it has evolved into the national anthem for the United States and is played at official events, schools, and sporting events. This anthem is a means to bring Americans together to remember the United States' perseverance in the face of adversity and as a stage that Americans can use to protest unjust policies.