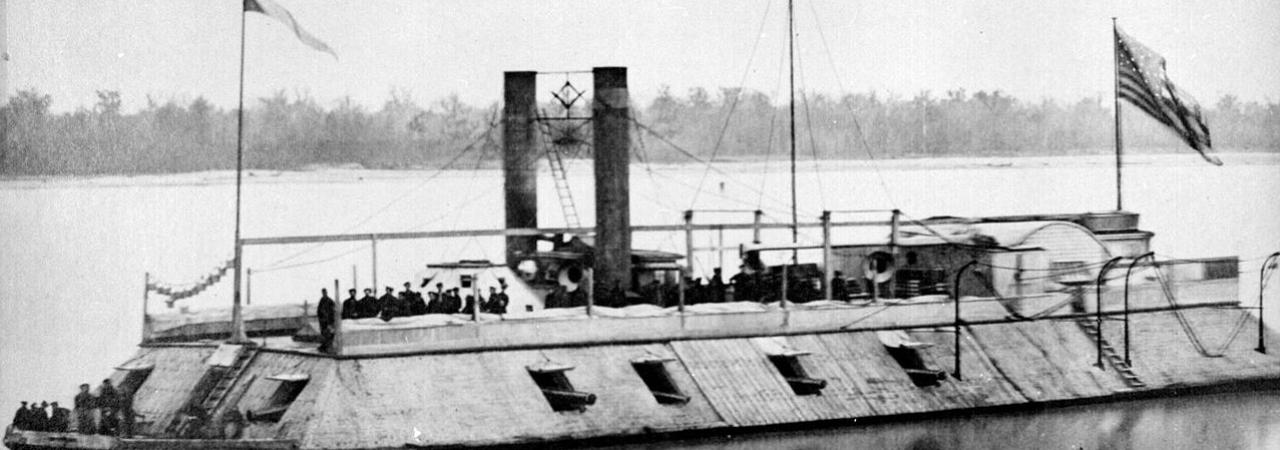

Civil War Ironclad, the USS Baron DeKalb.

During the first year of the Civil War, the U. S. Navy developed into a powerful weapon that helped the Union win the ultimate victory.

As 1861 dawned and the last months of peace slipped away, the U.S. Navy found itself at the forefront of the secession crisis. The Confederates threatened to seize Federal property in the seceded states, demanding the surrender of Fort Sumter in South Carolina and Fort Pickens in Florida. At both forts, the army garrison commanders refused to give in to Rebel requests and instead consolidated their troops behind the guns of the massive brick structures. President Abraham Lincoln, inaugurated on March 5, recognized the strategic military value of Sumter, which defended Charleston, the second largest seaport in the Confederacy, and of Pickens, which defended the naval repair base and coaling station at Pensacola. In early April, Lincoln sent expeditions of infantry, artillery, and supplies to reinforce both forts, escorted by powerful navy warships. At Fort Pickens, five companies of soldiers were successfully landed on April 12, and the continued presence of the steam frigate USS Powhatan offshore prevented an immediate attack on the fort. At Fort Sumter, however, the expedition was turned back as the Confederates bombarded the fort the same day that Pickens was resupplied. The war was on, and the relief expeditions (even though their results were mixed) marked the beginning of a close relationship between the Army and Navy that would evolve over the rest of the year.

The Union Navy at the beginning of the Civil War was a small but modern force. Around 90 vessels of all types were in the Navy’s inventory. Most of the vessels were technologically up to date: 24 of the newest ships were built with steam propulsion that drove a screw propeller or paddle wheels. Most of the new warships carried large-caliber, rifled guns that could fire explosive shells, and many were mounted on pivots that could be trained to either side. The largest and most powerful vessels were six ships of the Niagara- and Merrimack- classes of steam-powered frigates (mounting up to 40 guns each) and five ships of the Hartford- class of steam-powered sloops-of-war (16-26 guns each). These big ships were designed and built to be an equal match against similar vessels in foreign navies. Six smaller steam gunboats like the USS Mohican (between 6 and 9 guns each) built in the two years immediately prior to the war augmented the front-line battle force. Around 70 other ships of various types rounded out the fleet. The pre-war Navy was designed to fight other ships to protect the U.S. coasts; few of the ships were built to take naval combat up rivers, and none were configured with the right combination of armament, speed, and shallow draft needed to enforce a coastal blockade.

This modern force of ships required equally modern support facilities ashore. Steam engines required machine shops, boiler works, spare parts manufacturers, and other equipment that did not exist in the age of sail. New, large-caliber rifled guns required special mounting and ammunition. Shipyards along the Atlantic Coast at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Norfolk, Pensacola, and Mare Island Shipyard in San Francisco Bay, had grown to serve the Navy’s needs and were frequently populated with warships. In April 1861, some 48 naval vessels, about half the fleet, were laid up for long-term repairs or maintenance in various shipyards. Steam engines also required prodigious amounts of coal to fire their boilers. Coaling stations as distant as Key West provided the fuel the ships needed to operate, frequently at long distances from where they were needed. By the end of 1861, Union warships were consuming 3,000 tons of coal per week, and as much as one-fifth of the operational fleet at sea was either heading to or returning from a coaling station. The Union’s naval infrastructure was dealt a crippling blow on April 20, 1861, when the ill-conceived and botched evacuation of the Norfolk Naval Shipyard at Gosport, Virginia led to the Confederate capture of over 1,000 naval guns, irreplaceable dry dock, and repair facilities. Eight warships, including the steam frigate USS Merrimack, were also surrendered. The loss of the facilities at Norfolk meant the Union Navy had no base for fuel or maintenance between the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

After Fort Sumter fell, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to fill the ranks of new Army regiments. On May 3, 1861, he added a call for 18,000 new sailors and 1,000 marines to take the war to sea. The Navy increased in size from 7,600 sailors in March 1861, to 22,000 that December. The number of officers rose from 1,300 in 1861, to 6,700 by the end of the war. A lack of qualified sailors plagued the Navy for most of the first year of the war. Navy recruiting officers competed with their Army counterparts over who could offer a bounty to convince a man to enlist as a soldier. Fishermen and merchant marine sailors with seagoing skills and experience made up most Navy enlistees in 1861, but they had little knowledge of discipline, regulations, or weapons. Age, physical ability, and U.S. citizenship requirements were frequently ignored, and many boys under 16, old men, and foreigners found their way onto Navy crew lists. The enlistment of African Americans early in the war helped alleviate manpower shortages. In September 1861, Gideon Welles, U.S. Secretary of the Navy, ordered that Black refugees could be enlisted in the Navy – a full year before the Union Army raised Black regiments. Officer ranks were particularly difficult to fill: almost half of the officers on active duty in 1861 left to join the Confederacy. To compensate, the upper three classes at the Naval Academy were commissioned into service, resulting in many 19-year-old lieutenants. Authorization of bounties and draft quotas helped to ease the crew shortages, as did the transfer of army regiments into naval service.

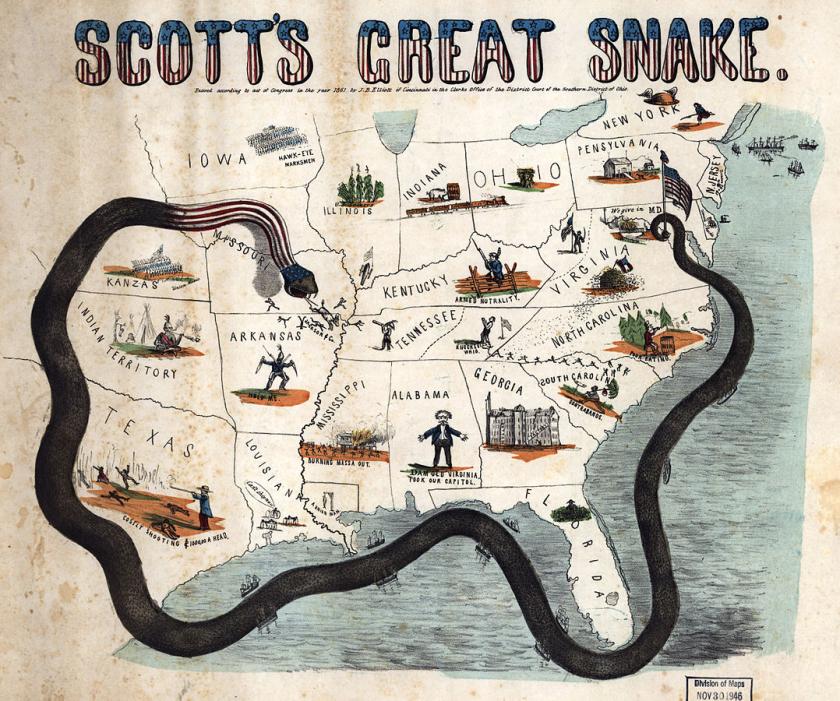

During the earliest days of the war, Lincoln and his cabinet held meetings to develop a strategy to suppress the rebellion. Lincoln favored a policy of economic subjugation of the Confederate states while also defeating them militarily. The “Anaconda Plan,” favored by general-in-chief Winfield Scott, fit both goals and demanded a heavy investment by the Navy. The plan called for a Union blockade of southern ports to cripple the Southern states' ability to trade cotton, the backbone of the Confederate economy. Simultaneously, Union Army and Naval forces would press southward down the Mississippi River to cut the Confederacy in two. The blockade was a controversial proposal. A blockade was understood to be an act of war between belligerent nations, a distinction Lincoln was reluctant to make regarding the rebelling states. Administratively closing Rebel-held ports was an option, but would not permit search and seizure of vessels outside of U.S. territorial waters. If the ports were closed, violators would need to be tried in state courts where the port was located, an impossibility since they fell under Confederate control. Under international law, a blockade was a deterrent that Great Britain and France, both potential military and commercial trading partners of the Confederacy, would be forced to acknowledge. Lincoln, accepting the risk in identifying the South as a belligerent nation, signed the order establishing the blockade on April 19, 1861, just five days after the fall of Fort Sumter.

The Union Navy reacted quickly. The steam frigate USS Niagara arrived off the port of Charleston on May 10, and the sloop USS Brooklyn arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi River, 90 miles downstream from New Orleans on May 27, establishing a Union presence at the South’s two largest ports. Other blockading warships were posted at Hampton Roads, Savannah, Pensacola, and Key West by the first week of June. The Anaconda Plan, however, would require far more warships than the Navy then possessed to close off some 3,500 miles of Confederate coastline. International law required that the blockade must be effective, therefore, finding more ships for continuous blockade duty was crucial. In response, Union Navy Secretary Gideon Welles instituted a crash ship buying program. Hundreds of Northern commercial ships were bought or leased and pressed into navy service. Almost any vessel that could mount a gun or two on its superstructure was put on blockade duty. Decks were strengthened, magazines were built below the waterlines, and crew quarters were expanded. Passenger ships became troop transports, double-ended ferries now carried artillery and supply wagons, and bulk cargo ships transported desperately needed coal. Steamboats on the western rivers were bought and sided with heavy wooden timbers to protect their deck-mounted engines, earning them the nickname “timberclads.” Repairs on existing Navy warships laid up in shipyards were hurried along and others were recalled from overseas stations, so that by the end of the 1861, the active number of Navy vessels rose from 42 to 264.

Gideon Welles also acted in the first months of 1861 to build new classes of warships that would have a direct effect on the war. On June 29, Welles signed building contracts for 23 new Unadilla-class gunboats. These steam-powered ships were rigged as two-masted schooners and had a draft of only nine feet, making them ideal for operating as blockade vessels in the restricted inlets and shallows along the Confederate coast. Built in 7 different shipyards, they were armed with a mix of five smoothbore and rifled guns, and their wooden hulls were reinforced with iron braces. Most were built and launched within three months, earning them the nickname “90-day gunboats.” Although their speed was only around nine knots and their engines were frequently unreliable, the versatile Unadilla-class ships alone were responsible for the capture of 10 percent of all blockade runners, and they took part in nearly every naval battle of the war.

Union military planners were keen observers of naval technological advances that were taking place in Europe. For a decade, England and France had experimented with wooden vessels covered with iron plates to provide protection from high-powered, rifled guns firing explosive shells. Each country had launched their own iron-covered warship, and American shipbuilders and army commanders in 1861 sought the advantages of iron protected gunboats to operate on the western rivers, which were lined with Confederate forts and shore batteries (the Navy would take over control of gunboat operations on the rivers in 1862). On August 7, 1861, U. S. Army quartermaster general Montgomery C. Meigs awarded a construction contract to James B. Eads to build 7 ironclad gunboats for army operations along the Mississippi River. The squat, broad-beamed, sloped-sided vessels were designed by engineer Samuel Pook and were nicknamed “Pook’s Turtles.” The ships, named for cities in the western states, carried 13 guns as heavy as 43-pounders facing forward, to the sides, and astern. The boats combined firepower, protection, and mobility needed on the rivers and they served the Army and later, the Navy, well into 1862 and beyond.

The same day that Meigs ordered the city-class gunboats to be built for the army, Welles advertised for proposals to construct "iron-clad steam vessels of war" for the Navy. The newly-established Ironclad Board of three senior naval officers ultimately received 17 designs for new ironclad warships, but approved only three for construction. The most revolutionary design of all was an iron-hulled steam vessel with a low freeboard, and a single, revolving two-gun turret on its deck. Named the Monitor, the warship was designed by Swedish engineer John Ericsson, who had pioneered the development of propellers and improved steam engines. The vessel’s design was controversial: no iron ship without sails and so few guns had ever been built before. The design won the approval of President Lincoln, and construction of the USS Monitor began at the Continental Iron Works in Brooklyn, New York on October 25, 1861. Construction also began on the other two approved ironclad designs before 1861 was over. The USS Galena (6 guns) and USS New Ironsides (18 guns) were more traditional wooden, steam-powered vessels with auxiliary sail power, but both were built with heavy plates of iron on the sides of their hulls.

As the Union’s ship buying and building program grew, blockade enforcement and combat operations against the Confederacy began within weeks of Fort Sumter’s surrender. On May 7, 1861, the Union gunboat USS Yankee traded gunfire with Confederate batteries at Gloucester Point near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Further north, on May 24, the crew of the USS Pawnee received the surrender of Alexandria, Virginia on the Potomac River, just opposite Washington, D.C. There were frequent clashes between Union gunboats and Confederate artillerymen along the Potomac during most of the first summer of the war, including a failed landing by 50 Union sailors at Mathias Point, midway between Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake Bay on June 27. Meanwhile, at sea, the Confederate privateer schooner Savannah was captured by the 7-gun brig USS Perry off the South Carolina coast on June 3. Three days earlier, Perry had captured the blockade runner Hannah M. Johnson off Point Lookout, North Carolina, and before returning to port she turned two British ships away from the blockade line. Just three weeks later, the frigate USS St. Lawrence captured the privateer Petrel in the same waters.

Although there were some victories and the Union Navy was growing fast, the blockaders struggled to be effective through much of 1861. On June 3, the Confederate commerce raider CSS Sumter broke through the Union blockade of the Mississippi River. Sumter captured 8 Yankee merchantmen around Cuba before moving into the Atlantic, raising an alarm up and down the coast. To ease blockade command and control difficulties, Welles divided the fleet into the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, covering Virginia to Key West, and the Gulf Blockading Squadron, stretching from Key West to the Mexican border. In mid-June, Welles authorized the establishment of a Blockade Board, a group of senior navy officers, coastal survey experts and army engineers to recommend solutions to the logistical challenges facing the blockade. From June to September, the Board deliberated and submitted recommendations to Welles. In July, the Board recommended splitting each blockading group in half operationally, into North and South squadrons along the Atlantic coast and East and West squadrons inside the Gulf of Mexico. This change eased the communication and supply challenge so that every ship within each of the four new squadrons was only two days sailing distance from their operational commander. The most significant of the Board’s recommendations was to establish new bases along the Confederate coasts for coaling and maintenance of the blockading warships. The Board proposed the capture of Cape Hatteras in North Carolina, Port Royal in South Carolina, Fernandina in Florida (at the Georgia border), and Ship Island on the Gulf coast of Mississippi. Based on the Blockade Board’s recommendation, Union army and navy planners began the first combined operations of the war.

On August 28, Union warships opened fire on Forts Clark and Hatteras guarding Hatteras Inlet in North Carolina. The next day, Army troops landed and captured the forts along with 700 prisoners. With control of Pamlico Sound, Union warships gained access to the mouths of the rivers leading deep into the North Carolina interior, and most of the state’s northern seacoast fell under Union control. The sheltered anchorage at Ship Island was captured by the USS Massachusetts in September 1861, breaking up coastal shipping between New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, and providing a base for future operations in the Gulf of Mexico. On November 7, a fleet of 77 warships under Flag Officer Samuel F. DuPont steamed into Port Royal Sound in South Carolina. Forts Walker and Beauregard guarding the harbor were battered into submission by the big warships. About 13,000 Union infantrymen landed after the battle, occupying Beaufort and establishing a coaling station there. The captures of Hatteras, Ship Island and Port Royal were among the Union’s few victories of 1861 (Fernandina fell to a Union naval force in March, 1862).

Union warships also made progress on the western rivers in 1861. On September 4, the timberclads USS Tyler and USS Lexington engaged Confederate gunboats and shore batteries at Hickman and Columbus, Kentucky as Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant sought victory over Rebels in that border state. Two days later, the two gunboats spearheaded Grant’s drive to seize strategic Paducah near the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. On November 6, Tyler and Lexington escorted army transports loaded with Grant’s 3,100 infantrymen down the Mississippi River from Cairo, Illinois to the river town of Belmont, Missouri. The 8-inch and 32-pounder guns of the Tyler and Lexington provided support to Grant’s regiments as they fought with Confederate infantry ashore by engaging Rebel batteries along the river. The two gunboats also provided cover for the Federal soldiers as they were withdrawn after the battle. Despite having no written doctrine directing the support of combined forces and no recent joint army-navy combat experience, Grant and other Union army commanders learned the value of gunboats and would continue to operate closely with the Navy for the remainder of the war.

At the end of 1861, one event at sea nearly derailed all the progress the navy had made in establishing the legitimacy of the blockade in the eyes of Great Britain and France. In early November, the steam frigate USS San Jacinto, under the command of Captain Charles Wilkes, on patrol in the western Caribbean Sea searching for Rebel commerce raiders, stopped in Cienfuegos, Cuba to replenish supplies. There, Wilkes learned that two Confederate diplomats, James M. Mason and John Slidell, had slipped through the blockade at Charleston and were in Havana for a brief stop on their way to England. It was widely known that the Confederate government was seeking closer ties to Great Britain and France, and that Mason and Slidell had been sent to London and Paris to make the case for increased European support for the Confederacy. Wilkes formed a plan. On his own, he determined Mason and Slidell to be “contraband” of war, subject to seizure. Wilkes moved his ship to Havana and waited. On November 8, San Jacinto fired a shot across the bow of the British steamship RMS Trent, carrying the two diplomats, and brought the ship to a stop. Although the Trent was a neutral vessel transiting through international waters from one neutral port to another, Wilkes took Mason and Slidell captive and let the Trent go. Reaction on both sides of the Atlantic was swift. Northern newspapers trumpeted the capture of the Confederates. British politicians protested the interference, demanding an apology from the Lincoln administration and the return of the diplomats. The Admiralty in London began a military build-up in Canada and in the western Atlantic. In response, some in the American press called for war with Great Britain. Negotiations to end the crisis moved along, as Lincoln sought to avoid “two wars at one time.” U. S. Secretary of State William Seward proposed a compromise, wherein the U. S. would claim that Wilkes acted without orders and failed to bring the Trent into port as a prize, as was required by international law. The danger passed, Mason and Slidell were released, and although Great Britain later provided support to the Confederacy, it avoided further confrontation with the government in Washington.

Enforcing the blockade was the most daunting mission the Union Navy faced in the first year of the war. There was little doubt that the early blockade was weak; as few as 28 vessels were captured or destroyed between April and December 1861. During that period, some 150 vessels arrived unmolested in the port of Charleston alone. Most estimates concur that overall, around 85 percent of attempts to run through the blockade during the war were successful. But as more ships and crews were added to the Union fleet, the blockade became more effective. The blockading squadron at Charleston grew from one ship to nine by the end of 1861, and grew even larger later. While it is true that many valuable weapons and other military supplies made it through the blockade onto Confederate shores, the economic warfare that Lincoln intended to wage against the Confederacy began to swing in favor of the Union. In the words of Gustavus Fox, the Union assistant secretary of the Navy, the measure was "not by what entereth into their port's but what proceedeth out." Cotton exports after the implementation of the blockade dropped to 10 percent of pre-war levels, wrecking the Confederate economy. Over four years of war, around 8,000 successful runs were made through the blockade, yet more than 20,000 vessels used Southern ports during the four pre-war years. The ships that became successful blockade runners were much smaller vessels that could carry far less cargo and represented only a small fraction of the South's pre-war, commerce. Even Confederate diplomat John Slidell admitted that “the risk of capture [running the blockade] was sufficiently great to deter those who had not an adventurous spirit from attempting it.” While never perfect, the blockade that began in 1861 contributed significantly to the destruction of the Southern economy and helped lead to Union victory.

The Union Navy began the war facing many challenges. Ships, sailors, and repair stations were in short supply. No effort was spared by Gideon Welles and others to enforce the blockade and cooperate with the Army. New gunboats, ironclads, and captured ports began to turn the tide against the Confederacy as 1861 turned into 1862 and beyond.

Further Reading:

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 6.

- Guns for Cotton: England Arms the Confederacy By: Thomas Boaz.

- Commander Will Cushing: Daredevil Hero of the Civil War By: Jamie Malanowski.

- Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig L. Symonds.

- War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865. By: James M. McPherson.

- Now For the Contest: Coastal & Oceanic Naval Operations in the Civil War

By: William H. Roberts. - A History of Ironclads By: John V. Quarstein.

- Sea Wolf of the Confederacy: The Daring Naval Raids of Lt. Charles W. Read. By: David W. Shaw.

- Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig L. Symonds.

- The Civil War at Sea By: Craig L. Symonds.

- Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference By: Margaret E. Wagner and Gary Gallagher.