The Civil War on the water was marked by bold strategy, technological innovation, and unflinching bravery. These are a few of the actions that shaped the course of the struggle.

The Battle of Port Royal

November 7, 1861

After foul weather compelled an infantry landing to be cancelled, Union naval officers took it upon themselves to attack the fortifications protecting Port Royal Sound, South Carolina. The resulting four-and-half hour gun battle exacted a heavy toll on the ships of the fleet as well as on the Confederate garrison. The defenders withdrew in the afternoon and left the sound in Union hands. The battle opened a vital approach to the Charleston Harbor, allowing Union ships to tighten the blockade on one of the Confederacy's largest seaports.

The Battles of Forts Henry and Donelson

February 6-16, 1862

Working in conjunction with Ulysses S. Grant's infantry, Andrew H. Foote led a flotilla out of Cairo, Illinois to attack Fort Henry on February 6, 1862. An fierce naval bombardment proved essential in the capture of the fort, which opened the Tennessee River to the depredations of his gunboats. Pivoting east, the combined arms force attacked Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River less than a week later. The fall of this fort opened up the Cumberland and forced the surrender of Nashville, Tennessee by the end of the month. Nashville was the first Confederate state capital to fall into Union hands.

More About Fort Donelson More About Fort Henry

The Battle of Hampton Roads

March 8-9, 1862

On March 8, Union blockaders were stunned by the approach of the CSS Virginia, one of the first ironclad warships the world had ever seen. The Virginia had devastated the timberclad fleet before nightfall. The next day, the USS Monitor, the North's own ironclad, moved out to challenge the Virginia. A day of desperate combat resulted in a stalemate, with both ships limping back for repairs. In this, the first battle between ironclads in world history, the future of naval warfare was revealed.

More About Hampton Roads Ships of the Civil War

The Battle of Island No. 10

February 28-April 8, 1862

The fortress at Island No. 10 protected the Mississippi River as it wound south into the Confederacy. A Union siege was supplemented by firepower from a squadron of gunboats as well as the mobility afforded by nearby naval transports. When the garrison finally surrendered, it marked the first Confederate position lost on the Mississippi River.

More About the Vicksburg Campaign

The Capture of New Orleans

May 1, 1862

From the fall of 1861 to the spring of 1862, the Union and Confederate navies dueled in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. New Orleans was the South's largest city, a vital hub of commerce, and contained one of the few functioning shipyards available to the Confederacy. In April of 1862, Commander David Farragut led a flotilla up the Mississippi River from the Gulf, pummeling the river fortifications around the city and being pummeled in return. After two weeks of stubborn resistance, Farragut had passed the forts and the guns of his ships commanded the city. On April 25th, Farragut demanded the surrender of the city. A small expeditionary force captured New Orleans at the beginning of May. In addition to the damage inflicted by the loss of such an important city, Farragut's actions were a striking demonstration of the military advantages to be gained by steam technology and the ability to travel against a river's current.

The Battle of Drewry's Bluff

May 15, 1862

When the Union advance during the Peninsula Campaign forced the destruction of the ironclad CSS Virginia, which could not navigate in shallow waters inland and was thus left without a base, the only defense left on the James River was Fort Darling on Drewry's Bluff. The Union Navy took advantage of this apparent weakness, throwing a squadron of three ironclads and two wooden gunboats against the fort while McClellan's infantry marched on Richmond along the line of the York River. With the help of a battery salvaged from the guns of the Virginia, the ad hoc force manning Fort Darling decisively repulsed the Union fleet just seven miles from the Confederate capital.

The Battle of Memphis

June 6, 1862

With the Union Navy making relentless progress down the Mississippi River, the Confederacy hastily assembled a fourteen-boat "River Defense Fleet," composed of merchant steamers and manned by civilian crews, in an attempt to turn the tide of the river war. Eight of these boats faced down a Union fleet of five ironclads and two rams at Memphis, Tennessee on June 6, 1862. Both sides suffered from incoherent command structures, and the battle soon became a swirling melee with little coordinated action. The vastly inferior arms and armor of the Confederates became apparent as vessels rammed into each other and exchanged gunfire at point-blank range. By the end, seven of the eight Southern gunboats were out of action compared to just one Union ram. The battle cleared the way for Union forces to move further south and lay siege to the fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The Battle of Fort Hindman/Arkansas Post

January 9-11, 1863

Having fought their way down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas River, Union forces were diverted by the Confederate base at Fort Hindman, also known as Arkansas Post. If they bypassed the position to advance further down the Mississippi, raiders could use the fort as a staging post for damaging attacks on the vulnerable shipping in the fleet's rear. Unwilling to thus expose themselves, infantry commander John McClernand and naval commander David D. Porter turned to the attack. The ensuing operation was an impressive display of combined arms strategy: gunboats suppressed the fort's batteries to allow the soldiers to deploy, then menaced any potential retreat after the infantry attack began. Fort Hindman fell on January 11, 1863, resulting in the largest surrender of Confederates west of the Mississippi River until the end of the war.

The Vicksburg Campaign

December 1862-July 4, 1863

By 1883, the fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi was the last point of major Confederate resistance on the Mississippi River. Without control of the Mississippi, the Confederacy would be geographically cut in half while North regained control a vital shipping lane. Although the fort was in a position of great natural strength and bristled with a formidable array of heavy artillery, vice-like naval pressure from both directions combined with a stubborn siege eventually starved the Confederate garrison into surrender on July 4, 1863. This loss, combined with the loss at the Battle of Gettysburg the day before, is generally considered to be the turning point of the Civil War.

More About the Vicksburg Campaign » | More About the Battle of Vicksburg »

The Siege of Charleston Harbor

July 19, 1863-September 7, 1863

Charleston, South Carolina was an important Confederate port and haven for blockade runners for most of the Civil War. In the summer of 1863, the Union blockading squadron outside of Charleston attempted to force the city into submission with a prolonged bombardment. Although the fleet made gains, particularly in the capture of Fort Wagner and the reduction of Fort Sumter, the Confederates defending the harbor refused to surrender, and in fact, held out until infantry under William T. Sherman seized the city at the end of the war.

The Second Battle of Sabine Pass

September 8, 1863

France took advantage of the domestic strife in the United States during the Civil War to breach the Monroe Doctrine and establish a colonial government in Mexico. In response to this threat, Abraham Lincoln ordered increased military operations in the Texas area to deter French support for the Confederacy. The Second Battle of Sabine Pass was one such operation, as a squadron of four Federal gunboats--escorting transports holding 5,000 infantrymen--sought to force their way into the mouth of the Sabine River from the Gulf of Mexico. Punishing artillery fire from a Confederate garrison consisting of thirty-six men sank two gunboats and forced the invading force to withdraw. Despite this feat, which many call the most one-sided victory of the war, French Mexico and the Confederacy never joined forces.

The H.L Hunley Sinks the USS Housatonic

February 17, 1864

The Hunley was an eight-man submarine pressed into service by the Confederate government. Although initial tests resulted in two sinkings and thirteen deaths, the Confederate navy stubbornly put the Hunley to sea for a live combat mission on February 17, 1864. Slipping out of Charleston Harbor, the Hunley targeted the blockading USS Housatonic with a spar torpedo, which was essentially a bomb mounted on a twenty-two foot pole in front of the submarine. The Hunley sank the Housatonic, the first successful submarine attack in world history. Unfortunately for her crew, the Hunley herself sank shortly thereafter. Although the Confederate government did not salvage the ship for a third time, it was rediscovered and raised in the year 2000.

The Battle of Plymouth

April 17-20, 1864

In one of the last Confederate victories of the war, the ironclad CSS Albemarle drove off the Union naval squadron supporting the defenders of Plymouth, North Carolina and ensured the success of the Confederate infantry assault. The Albemarle, built in a cornfield due to a lack of shipyard facilities, controlled the Roanoke River throughout the summer before being sunk in a daring attack on October 28, 1864.

CSS Alabama vs. USS Kearsarge

June 19, 1864

The CSS Alabama was the most successful vessel in the Confederacy's small fleet of commerce raiders. Over the course of a 22-month cruise she captured and burned nearly 70 Union traders, never docking in a Confederate port. While she was resupplying at Cherbourg, France, Raphael Semmes, captain of the Alabama, challenged the nearby USS Kearsarge to a fight. The Kearsarge accepted and the Alabama lost, ending the illustrious sailing career of the ship that gave rise to the chant "Roll, Alabama, Roll." The international visibility of the Alabama, a British-constructed ship that frequently sheltered in foreign ports, shaped the way many people outside of the United States viewed the Civil War.

The Battle of Mobile Bay

August 5, 1864

Mobile Bay was protected by three fortresses, a small fleet, and an extensive underwater minefield that combined to protect the Southern port of Mobile, Alabama. Admiral David Farragut's bold and successful attack secured Union control over the Gulf of Mexico and was widely covered in the Northern press, not least for Farragut's alleged exclamation of "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" while ordering his ships to blast through the minefield. The victory was an important boost to civilian morale and buoyed Abraham Lincoln during the difficult election of 1864.

The Bahia Incident

October 7, 1864

Confederate commerce raiders were responsible for the reduction of approximately one-half of the Northern merchant fleet, a point of significant frustration for the captains of the ships sent out to challenge them. The CSS Florida was one such raider, with over fifty captures to her name. She was discovered while resupplying in Bahia, Brazil, by Napoleon Collins, in command of the USS Wachussett. On the night of October 7, 1864, the Wachussett crept into the harbor and opened fire on the unsuspecting Florida before ramming into her hull. A boarding party secured the surrender of most of the crew, but some leapt overboard and escaped into Brazil. Collins's flagrant abuse of Brazil's sovereignty and neutrality sparked a diplomatic crisis.

The Second Battle of Fort Fisher

January 13-15, 1865

Fort Fisher protected Wilmington, North Carolina, which by January of 1865 was the last remaining seaport in Confederate hands. Admiral David D. Porter and Major General Alfred Terry's amphibious assault on the fort led to a grueling battle in which fifty-one soldiers, sailors, and marines won the Medal of Honor. The successful capture of Fort Fisher opened the path to Wilmington, the fall of which wiped out Southern seaborne commerce once and for all.

More About Fort FisherDavid D. PorterAlfred Terry

The Battle of Trent's Reach

January 23-25, 1865

While Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant faced each other down from the trenches around Petersburg, a squadron of Confederate warships sailed to attack City Point, Virginia, an important supply base for the besieging Union army. Although the squadron made early gains, four ironclads ran aground near Trent's Reach and a minefield deterred further progress by those ships still afloat. A determined counterattack forced the Confederate ships to withdraw, leaving Robert E. Lee to continue his desperate land defense around Petersburg unaided.

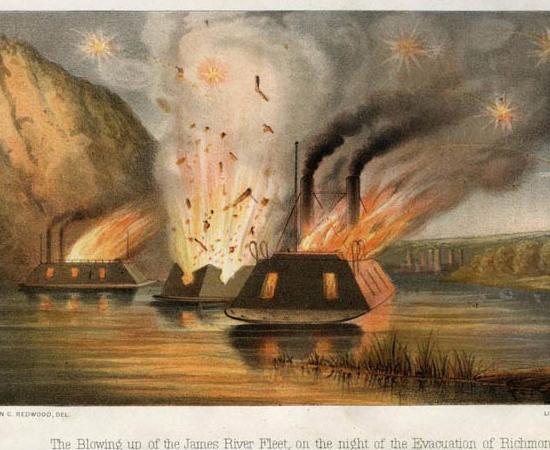

The Surrender of the CSS Shenandoah

November 6, 1865

The Shenandoah was a Confederate commerce raider that was slow to receive the news that the war had ended. It was not until August 2, 1865, more than two months after the surrender of the last major Confederate army, that a passing British trader informed the Shenandoah of the state of affairs. Reluctant to land in the United States and face charges of piracy, the Shenandoah's captain instead sailed to Liverpool and surrendered to the British government. The flag of the Shenandoah, now on display in the Collection of the American Civil War Museum, carries the distinction of being the last Confederate flag to be lowered during the war as well as being the only Confederate flag to circumnavigate the globe during the war.