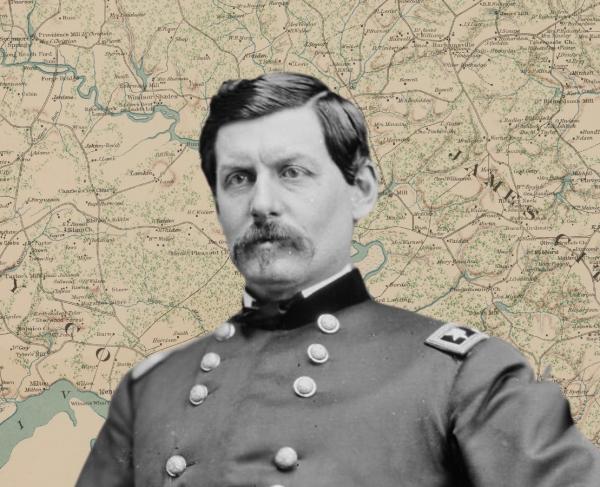

Steel & Steam

For centuries before the Civil War, large naval battles had not changed dramatically. Conflicts in the “Age of Sail” were fought by wooden, sail-driven ships carrying as many cannon as possible, which would generally pummel each other until one of them became so damaged that it could not keep up the fight. In the decade before the Civil War, however, major developments in naval technology – particularly in propulsion and artillery – forever changed the face of naval warfare. In the words of one historian, a British captain who fought the Spanish Armada in 1588 "would have been more at home in the typical war-ship of 1840, than the average captain of 1840 could have been...in the advanced [ship]types of the Civil War."

Steam

The first of these changes was the introduction of steam power. Steam engines had existed before the nineteenth century, but Robert Fulton built the first steam-powered warship in 1815 for the US Navy. By burning coal, paddlewheel or propeller-driven steamships achieved an unprecedented freedom of movement. Unlike sailing ships, whose movement relied heavily on the wind’s power and direction, “steamers” could more easily return upriver after transporting goods to port or continue a journey with weak or adverse winds.

Steam warships were slow to catch on, but by the late 1850s, all new warships built by the Navy featured steam engines. The significance of the steam was not necessarily obvious to outside observers – at least at first. The engines did not make the ships dramatically faster, and many steamships continued to use sails to preserve fuel on long trips. These ships looked and functioned much like ships from the age of sail except for the tell-tale smokestack rising above their decks. Nevertheless, because of their flexibility, steamers served as blockade runners, transports, and cruisers – and in virtually every role that could be found for them during the war. They also paved the way for other major developments in warship design.

Improved Artillery

Major artillery developments caused further change to warships. In the 1850s, several innovations in cannon construction enabled the military to build bigger, more accurate, and longer-ranged guns. One such change was conceived by John Dahlgren, a naval officer who developed a technique for reinforcing the breach of a cannon to better withstand the extra gunpowder needed to fire larger shells at greater distances. Furthermore, although both Union and Confederate navies continued to use smoothbore cannon, rifled cannon (which featured grooves on the inside of the barrel to impart a spin on the projectile) became increasingly common in the 1850s and 1860s. These weapons were significantly more accurate than their smoothbore predecessors, and when combined with the long range of newer naval guns, meant that naval battles could be fought at much greater distances.

These innovations were amplified by the widespread adoption of explosive shells, which had been developed in the 1820s. Several types of cannon shot existed in the centuries before the Civil War, but virtually all of them were designed to cripple a ship or kill her crew. Shells, however, contained a fuse timed to detonate after hitting the ship, meaning that a single shell could blow a sizeable hole in a wooden ship and send her to the bottom.

Ironclads

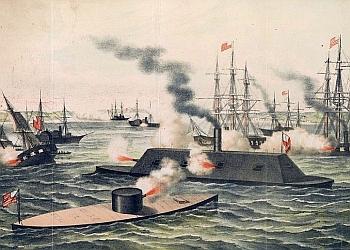

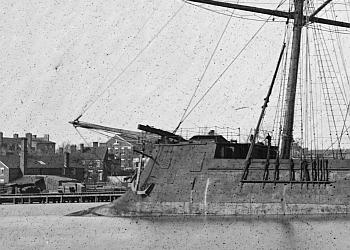

The developments in artillery and propulsion led to another key innovation: the ironclad. Realizing how tremendously vulnerable wooden ships were to destruction by long range, explosive cannon fire, naval architects began to dramatically improve ships' defenses by plating them with iron or steel. This casing made shells bounce off the ship, allowing ironclads to survive repeated direct hits. Ironclads were extremely heavy, so powerful steam engines took the place of sails, which were weaker and vulnerable to enemy fire.

The first ironclads were built in Europe just before the Civil War, but neither North nor South possessed any of their own when the war began. Both sides began building or converting ironclads of various shapes and sizes. Some ironclads were simply normal steamships covered with metal plates (called casemate ironclads), while the Union built a number of "Monitor" class gunboats that sat low in the water and utilized a revolving armored gun turret. Gunboats intended to sail on Western rivers typically had shallower drafts than their ocean-going counterparts, which were designed to be more stable in heavy seas. Union and Confederate ironclads first met in battle in March 1862 at the Battle of Hampton Roads – the world's first naval engagement between ironclad warships.

With the battle of Hampton Roads, naval warfare changed forever. The ironclads could defeat wooden warships with relative ease, and brushed aside all but the heaviest (or the luckiest) artillery rounds. Apart from piercing the sturdy armor, an artillerist fighting an ironclad could only hope to hit a smokestack or shoot through an open gunport. Even then, it was unlikely the shot would do significant damage. So powerful were the ironclads that they upset an ancient axiom of naval warfare that forts were stronger than ships. Traditionally, forts afforded protection from enemy fire, a stable shooting platform for gunners, and the ability to mount powerful guns that were too large or heavy for ships. These factors remained true, but the new ironclads also had defense from enemy fire. Because they could withstand more time near a fort, groups of ironclads were able to rush past forts to enter harbors, or even – on several occasions – defeat forts in artillery duels.

Rams

As it became clear that most cannon fire could not reliably stop ironclads, the Union and Confederate navies increasingly invested in alternative strategies. One of the responses to this problem was not really an innovation at all, but a return to the dawn of naval warfare. The ram was used as the principal weapon on ancient Mediterranean warships but had gone out of style as larger sailing-ships carrying cannon replaced oar-driven galleys. Steam engines, however, granted more maneuverability than sails, and when used in combination with heavy armor, could allow a ship to get close enough to ram and sink another ship (even an ironclad). Nevertheless, successfully ramming another ship was a difficult task that could sometimes damage the ramming vessel itself; rams once again drifted into obsolescence in the decades after the war.

Torpedos

In the South, where iron was scarce and the ability to make powerful steam engines was virtually nonexistent, Confederates were also forced to seek other methods of protecting their ports from an increasingly armored Union fleet. One solution was to deploy "torpedoes" – submerged explosives (which would be called sea mines today) that could detonate under enemy ships. Torpedoes, therefore, had the advantage of being able to attack an ironclad below the waterline, where its hull was most vulnerable.

When torpedoes proved successful, the Confederacy designed the first "torpedo boats," which carried mines on long spars in front of the ship. The boats sat low in the water so that they were harder to see, and presented a smaller target to cannon fire. On multiple occasions, torpedo boats (which were quickly adopted by the Union) were able to sail up to anchored ships and detonate torpedoes against the vessels’ hulls.

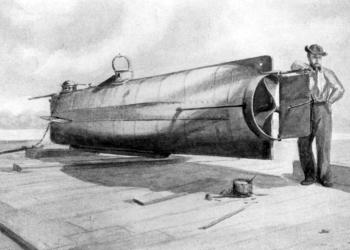

Submarines

Southerners took the concept of low-profile torpedo boats one step further with the development of several submarines. The first-ever submarine to destroy an enemy ship was the H.L. Hunley, which sank USS Housatonic near Charleston in February 1864. The Hunley was essentially a submerged torpedo boat that had been plagued by bad luck and technical problems since its creation – losing almost two full crews in training exercises. Her career was short-lived; the sub sank with all hands almost immediately after the attack, and no other submarines were able to achieve any notable success during the war.

These interrelated innovations in naval technology – along with other notable developments such as the first warship to use a revolving gun turret in combat (the USS Monitor) and the US Navy's first aircraft carrier (a barge for launching observation balloons) – mark the Civil War as the beginning of a new era in naval warfare. The technology of the Civil War became the new standard among world powers, and the heavily armored, steam-powered battleships (soon to be known as "dreadnaughts") served as key tools for projecting national power and played a dominant role in the diplomacy between the world's "Great Powers" in the years of frenzied imperialism leading up to World War I. It was almost a century before further innovations, such as the dramatic improvements to ship-borne aircraft, caused the US Navy to once again majorly reorient the designs and missions of its ships. Other Civil War-era innovations – like steel armor and submarines– are still central components of modern naval warfare.

Further Reading

-

War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 By: James M. McPherson

-

Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History By: Richard Snow

-

Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig Symonds

-

The Civil War at Sea By: Craig Symonds

Related Battles

369

24

322

1,500