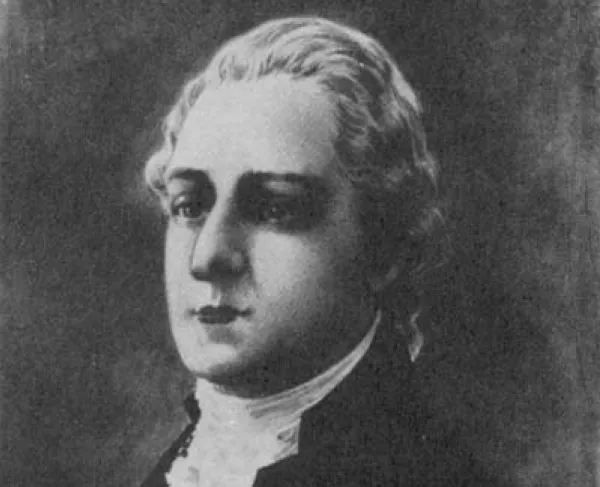

Dr. Benjamin Church

As a member of the Sons of Liberty and the first Surgeon General of the United States, Dr. Benjamin Church Jr. seemed to be a zealous patriot on the surface. However, Dr. Church can be considered American’s first traitor, before the more infamously known Benedict Arnold.

Benjamin Church Jr. was born on August 24, 1734, in Newport, Rhode Island to a prominent and well-connected family. He graduated from Harvard University at twenty years old in 1754. As was typical of the time when studying medicine, Rush served in an apprenticeship under Dr. Joseph Pynchon of Massachusetts before finishing his studies in London. While overseas, he met his wife, Hannah Hill, of Ross, Herefordshire, and traveled throughout Europe. He returned to Boston with his new bride and soon became a well-respected citizen and physician.

Throughout the 1760s and 1770s, he emerged as a prominent Whig, or supporter of the American Revolution, hobnobbing with Revolutionaries including John and Sam Adams, and Dr. Joseph Warren. After the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, that killed several colonists, Church not only examined the body of Crispus Attucks, but he was also asked to give an oration on the anniversary of the event in 1773 in which he said:

Mankind apprized of their privileges, in being rational and free; in prescribing civil laws to themselves, had surely no intention of being enchained by any of their equals; and although they submitted voluntary adherents to certain laws for the sake of mutual security and happiness; they no doubt intended by the original compact, a permanent exemption of the subject body, from any claims, which were not expressly surrendered, for the purpose of obtaining the security and defense of the whole: Can it possibly be conceived that they would voluntarily be enslaved, by a power of their own creation?

His support for the Revolution continued when in 1774 he was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and after the Revolution began, he was appointed to a committee “to consider what method is proper to take to supply the hospitals with surgeons and that the same gentlemen be a committee to provide medicine and other necessaries for hospitals”. In July 1775, the Continental Congress authorized the creation of a Medical Department with a Director General and Chief Surgeon. Dr. Benjamin Church was selected to serve as Director General, a role which ultimately made him the first Surgeon General of the United States. However, he only served that role for three months before he was court-martialed on accusations of treason.

Throughout the early months of 1775, Church corresponded with General Thomas Gage, a British general charged with trying to put down the revolution before it began. In this correspondence, Church helped supply information including the location of arsenals for the Patriots. This communication continued until a letter was intercepted. After a trip to Philadelphia, Church attempted to send a ciphered letter to Gage through a series of messengers who were to transport the letter by boat to the British army and then to its intended recipient. However, Church’s first messenger in this chain, an old mistress, gave the letter to a Rhode Island baker and Patriot, Godfrey Wenwood. Instead of passing the letter along the chain, Wenwood instead gave the letter to General Nathanael Greene and it eventually made it to General George Washington. In October 1775, when the letter was decoded, it was found to contain information about Continental Troops before Boston as well as Church’s previous failed attempts to get Gage information, solidifying the evidence that Church was indeed a traitor in the eyes of Washington. Church was arrested and the matter was presented to the Continental Congress in which Washington wrote:

I have now a painful though necessary duty to perform, respecting Doctor Church, the Director of the Hospital. About a week ago, Mr. Secretary Ward, of Providence, sent up one Wainwood, an inhabitant of Newport, to me with a letter directed to Major Cane in Boston, in occult letters, which he said had been left with Wainwood some time ago by a woman who was kept by Doctor Church. She had before pressed Wainwood to take her to Captain Wallace, Mr. Dudley, the Collector, or George Rowe, which he declined. She gave him the letter with strict injunctions to deliver it to either of these gentleman. He, suspecting some improper correspondence, kept the letter and after some time opened it, but not being able to read it, laid it up, where it remained until he received an obscure letter from the woman, expressing an anxiety as to the original letter. He then communicated the whole matter to Mr. Ward, who sent him up with the papers to me. I immediately secured the woman, but for a long time she was proof against every threat and persuasion to discover the author. However she was at length brought to a confession and named Doctor Church. I then immediately secured him and all his papers. Upon the first examination he readily acknowledged the letter and said that it was designed for his brother, etc. The army and country are exceedingly irritated.

When questioned about the letters, Church admitted sending the letters but did not admit treason. However, the evidence was hard to dispute. Church was court marshaled, removed from his post as Director General, and arrested. He was briefly jailed in Norwich, Connecticut, until January 1776 until he got ill and was allowed to live under house arrest at his home in Massachusetts until 1778 when he was named in the Massachusetts Banishment Act, forcing those who supported the British or “joined the enemies thereof” to leave the United States. He sailed from Boston headed for the Caribbean, but the ship was lost at sea, and Church likely perished along with it.

Historians to this day debate the reason for Church’s treason; maybe he was always a Tory loyal to the British Crown, or maybe he was in a large amount of debt and needed the money, or maybe he considered himself a mediator between the two enemies. But, when General Gage’s files were able to be opened in the early 20th century, it was hard to ignore the amount and content of information that was concealed and sent to British troops.

Further Reading:

- Revolutionary Surgeons: Patriots and Loyalists on the Cutting Edge by Per-Olof Hasselgren

- Dr. Benjamin Church, Spy: A Case of Espionage on the Eve of the American Revolution by John A. Nagy