Corinth

Second Battle of Corinth

Alcorn County, MS | Oct 3 - 4, 1862

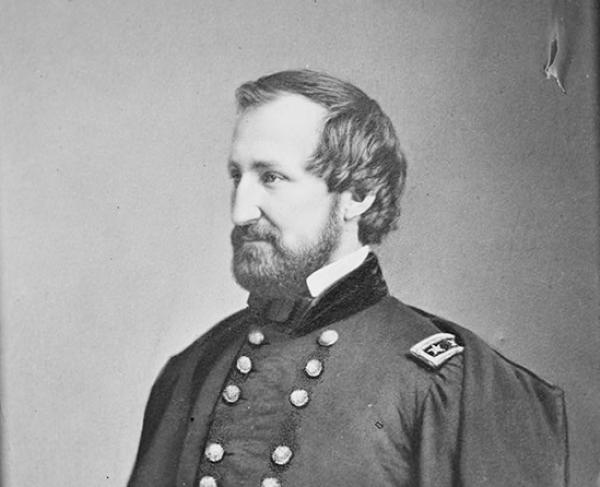

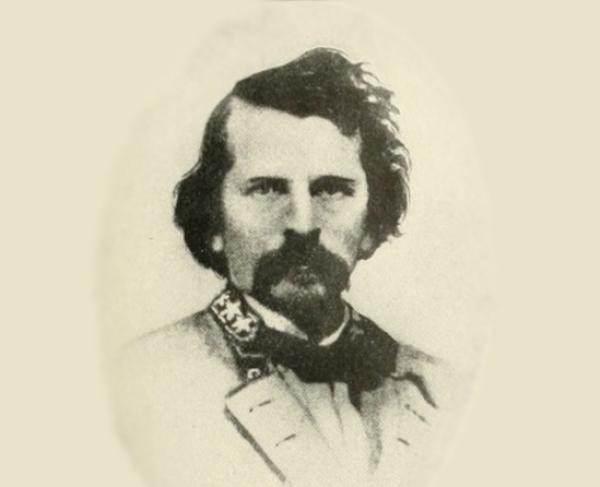

From October 3 to 4, 1862, a Confederate army under the command of Gen. Earl Van Dorn attacked the vital city of Corinth, Mississippi. During the two-day battle, Van Dorn’s army gained initial success but was ultimately defeated due to a stiff Federal defense led by William S. Rosecrans.

How It Ended

Union Victory. After opening up a second attack along the entrenched Federal lines, Van Dorn’s army was met with a stout Federal defense. With his men unable to break through the Federal defenses, Van Dorn decided to retreat from the field.

In Context

In the late summer of 1862, Confederate armies were on the march everywhere in the western theater. The main thrust was General Braxton Bragg and his Army of Mississippi, who were preparing to invade Kentucky, where he hoped to capture the state and force a turnaround in the Union gains earlier that year. To accomplish this, Bragg had to separate the two major Union armies in the area, the Army of the Ohio under General Don Carlos Buell, based in northern Alabama, and the Army of the Tennessee under General Ulysses S. Grant, based in the Memphis area. Bragg tasked both General Sterling Price and General Earl Van Dorn to keep Grant in lower Tennessee to combine their two armies and attack the vital southern town of Corinth, Mississippi.

Confederate general Earl Van Dorn knew that Union General William S. Rosecrans had 15,000 men at Corinth, with another 8,000 at the nearby garrisons at Iuka, Burnsville, Rienzi, Danville, and Chewalla. If Van Dorn moved quickly, he could strike before Rosecrans consolidated his forces, and, with 22,000 men, he would have a numerical advantage of about 3-to-2.

However, to be successful, Van Dorn needed the element of surprise. Without Rosecrans being aware, he moved his army from LaGrange to Ripley, where Gen. Sterling Price joined him on the 28th. On the 29th, Van Dorn’s army marched north toward Pocahontas, threatening the Union garrison at Bolivar. However, The effort to conceal his objective failed; Union General Ulysses S. Grant saw through the feint and ordered Rosecrans to concentrate his forces.

Unknown to Van Dorn, Rosecrans intercepted a message from Confederate spy Amelia Burton, who sent a letter to Van Dorn indicating that the Union defenses were weakest on the northwest side of town. When Rosecrans took command at Corinth on September 26, he immediately began improving the town’s defenses. By early October, Rosecrans had amassed almost the same number of men Van Dorn had.

During the night of October 2, Van Dorn held a council of war with his generals and laid out his plan for attacking Corinth. Though he had one or two good maps, Van Dorn drew a crude sketch on paper indicating how he wanted the army to maneuver. His division commanders thus went into combat the next day without a clear understanding of what Van Dorn wanted them to do.

October 3: At dawn on October 3, Van Dorn’s army advanced towards Corinth. At 10 a.m., Gen. Mansfield Lovell’s division ran into Federal skirmishers from Col. John M. Oliver’s brigade. Under pressure, Oliver’s men retreated to a hill near the old Confederate defensive lines used during the Siege of Corinth in May of 1862. After more Confederates arrived on the field, Oliver requested reinforcements. Rosecrans, without hesitation, sent Thomas J. McKean’s and Thomas A. Davies’ divisions. Both divisions were astride the Memphis road.

Van Dorn hoped that Lovell’s men would strike Rosecrans left hard enough that he would have to support it, leaving his right in a weakened state upon which Gen. Price would attack. However, Rosecrans’ men unknowingly left a gap in the middle between McKean and Davis large enough to exploit.

Once the Confederates attacked the Union line, they quickly realized there was an opening in the Federal lines and at once poured through the gap. By 1:00 p.m., Rosecrans decided to pull his men back several hundred yards into their inner lines.

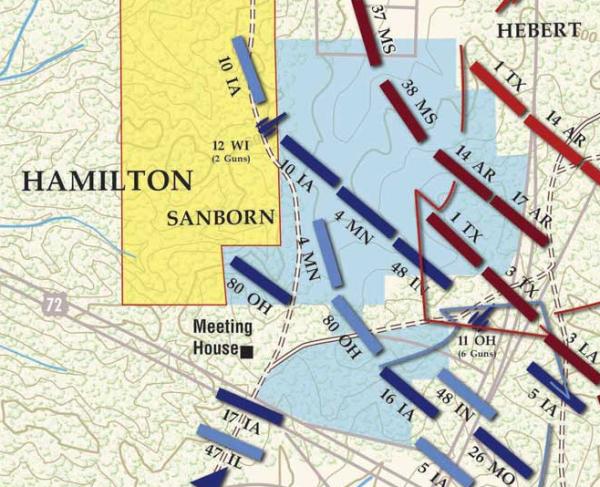

During this slow withdrawal, the general saw an opportunity to turn back the Confederate onslaught. Further to the Federal right was Charles S. Hamilton’s division which, for the most part, hadn’t seen action. Once the Confederate attack began to push back the Federals, Rosecrans sought to use Hamilton to swing around and hit the open Confederate left flank. Hamilton, unfortunately, misunderstood the order, and by the time his division was poised to attack, too much time had been lost, and ultimately it was called off.

With darkness overtaking the battlefield, both sides ended the fighting. Both generals believed that he could have won the battle that day with one more hour of daylight. Van Dorn believed he would have broken through the Union front, while Rosecrans believed Hamilton would have rolled up the Confederate left.

During the night, Van Dorn sent Major Edward Dillon forward to scout the Union lines, but he was stopped about 40 or 50 yards short when he spotted Union sharpshooters. Van Dorn and others heard the sounds of wagons which he interpreted as the sounds of axes, clearly indicating that Rosecrans was improving his defensive positions instead of falling back.

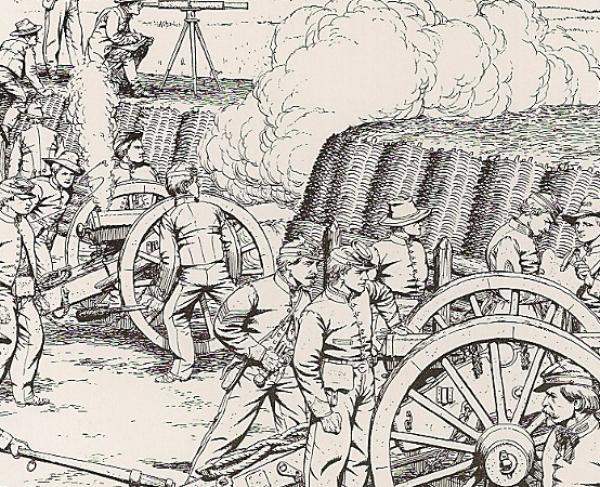

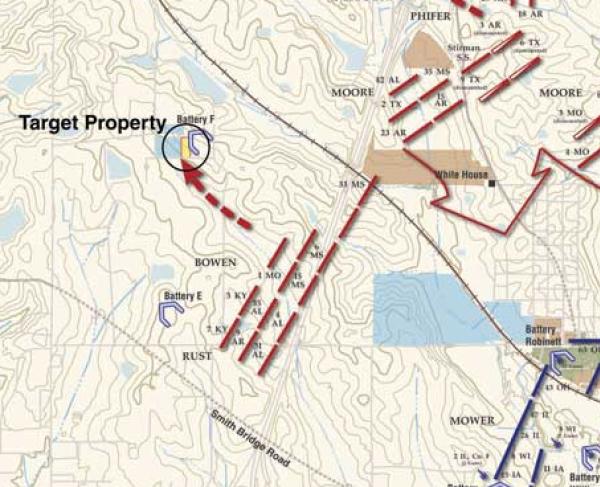

October 4th: Van Dorn’s plan for the 4th was to open the attack on the Federal right, with Louis Hebert’s division assaulting first light. However, Hebert became too ill, and one of his brigade commanders, Martin E. Green, had to take over. Green waited until 8:00 a.m., four hours after the intended time. The Confederate assault, however, was initially successful, with Green’s men temporarily taking control of Battery Powell, but due to a strong Federal counterattack led by Gen. Charles S. Hamilton, they were thrown back.

Once Green’s division attacked, Brigadier General Dabney H. Maury, to the left of Green, assaulted Battery Robinett. Maury’s men were met with a terrific musket and artillery fire from David S. Stanley’s division. Maury launched three attacks on the fortification but could not take it. However, men from Charles W. Phifer’s brigade found a hole in the Union line between Stanley and Davies’ division and quickly pushed through. Some of Phifer’s men managed to make it into the city of Corinth, but the Confederates were thrown from the city due to another strong Federal counterattack.

Just as Maury’s attack got underway, Gen. Manfield Lovell’s division was preparing to attack the Federal right flank; however, by the time Lovell was in position, word was received to pull back and cover the Confederate retreat.

2,359

4,838

By the late afternoon, Van Dorn realized his men were defeated and that more Union reinforcements had arrived from Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, forcing Van Dorn’s army to retreat towards Tennessee and then back into Mississippi.

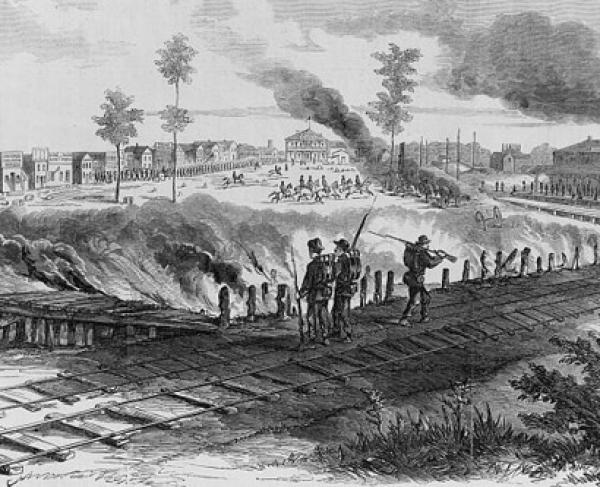

By the start of the Civil War, the city of Corinth was a hub of trade and commerce. The town alone had two significant railroads running through the city, the Memphis and Charleston and the Mobile and Ohio, not to mention five important roads leading to places like Memphis and Iuka. In the spring of 1862, a Union army under the command of William H. Halleck besieged the city and captured it in May of that year. By the fall of 1862, Confederate general Earl van Dorn was tasked with recapturing the vital city. After Van Dorn’s defeat, the Union army held Corinth for the rest of the war.

After gaining large swaths of ground and pushing the Federal defenders back into their inner lines, Van Dorn was confident that he had the Union army defeated. With nightfall taking over the battlefield, Van Dorn thought he could resume the battle the next day and sweep up what remained of the army. However, this assumption proved to be false. The Union army under William S. Rosecrans re-established their lines and was in a well-defended position to hold back the Confederate army the next day.

Corinth: Featured Resources

All battles of the Iuka and Corinth Campaign

Related Battles

23,000

22,000

2,359

4,838