Age of Enlightenment

Ironically, out of a period of chaos came an age of reason. Better known in history as the Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason, this was a period stretching from the late 17th century through the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. From the restoration of the monarchy following the English Civil War, “a rigorous scientific, political, and philosophical discourse” emerged in Europe and journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean to enlighten the minds of British colonists. Ideals such as natural law, liberty, progress, constitutional government, and separation of church and state became byproducts of the workings of the great minds that lived during the Age of Enlightenment. This range of ideas and values sparked an outpouring of discussion, debate, and publication that set in motion the ideas that lead to revolutions and rebellions.

Preceding, and to some historians a natural connection to, the Enlightenment was the Scientific Revolution. There is some overlap as historians debate where these two monumental ages begin and end. There is a disagreement of 50 years, with some arguing that the beginning of the Enlightenment was 1637 when Rene Descartes published his Discourse of Method. However, others mark the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica in 1687 as the end of the Scientific Revolution and the kick-off of the Age of Enlightenment. Regardless of when these two eras began, ended, or overlapped, historians do agree that this time frame began the emergence of the modern world. Custom and tradition, mainstays for centuries, were overtaken by exploration, individualism, and developments in industry and the world of politics.

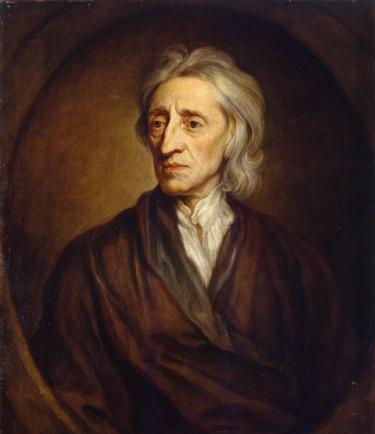

The concept that these ideas germinated in the great minds of particular colonists in North America was not far-fetched. As the 18th century progressed, colonists in North America were fond of newspapers, books, coffee shops, salons, and taverns; this led to further debate and expression of ideas. Burgeoning movements sprung up about individual liberty. In 1689, John Locke published Two Treatises of Government advocating a separation of church and state, religious toleration, and certain inalienable rights of the individual, among other premises. These sacrosanct or natural rights were God-given and cannot be given or taken away, and Locke narrowed them down to three: “life, liberty, and property.” Thomas Jefferson, writing 87 years later, echoed Locke when he penned the Declaration of Independence.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed

by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

The echoes of the Age of Enlightenment did not end with Locke’s influence on Jefferson and the seminal document of the United States. Francis Bacon advocated the scientific method, careful and repetitive experiments that could be replicated and logical thinking over theological synthesis and philosophical speculation. This provided the basis for the laws of reason.

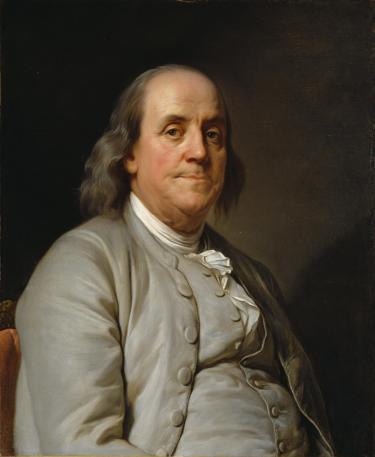

One of the better-known disciples of Enlightenment principles in America was Benjamin Franklin. In his writings, Franklin reflected on the way people view their own responsibility, how they are better themselves as individuals, and scientific experimentation. Many of his quips have been passed down in American history but when delving deeper into their meanings and advice, one sees elements of these principles of the Age of Enlightenment.

Other great Enlightenment era thinkers included Adam Smith, David Hume, Immanuel Kant and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, to name a few. Smith’s influential work, published in 1776, was entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. A central point of the work is the idea that the individual need to fulfill self-interest resulted in a benefit of the society as a whole. Smith advocated for no government interference in the market and that the three basic tenets of a government were to protect national borders, enforce civil laws, and engage in public works.

Hume—a philosopher, historian, economist and essayist—was another Enlightenment era thinker who had a direct impact on the ideology of the Founding Father generation. As early as 1771, Hume foresaw the fissure erupting between Great Britain and the American colonies, writing that the “union with America…in the nature of things, cannot long subsist." He continued to be a proponent of American independence throughout the early part of the 1770s. Even after American independence, Hume’s views continued to shape the burgeoning political narrative of the United States. One example with a direction connection is his view that no high office holder in the government should draw a salary impacted Benjamin Franklin’s thinking, leading that luminary of early America to propose the same clause at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

Immanuel Kant’s views on freedom of speech were embodied in the United States with the passage of the First Amendment along with the freedom to practice religion. Kant advocated for freedom of speech in the press, in public, where “one’s reason is all that matters.” Not only did Kant’s work have an effect in the fledgling United States, but also in the German principalities well into the 20th century.

Another enlightenment thinker was Descartes, who uttered the now famous quote “I think therefore I am,” was accepted as one of the most prominent figures in modern science and philosophy. He espoused a disbelief in authoritarianism, writing that individuals possessed a “natural light of reason,” and believed that the world was naturally rational and comprehensible. These echoed with revolutionaries as they reacted to absolutism in the form of monarchial governments and authoritarianism in the form of the Roman Catholic Church.

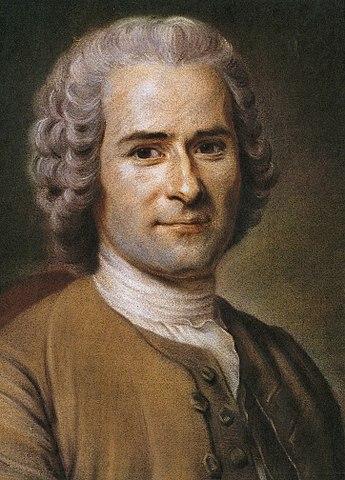

Lastly, Jean-Jacques Rousseau—a Genevan philosopher and writer—explored political philosophy, and his writings formed foundational pieces on modern social and political thought. He believed that people would give up unlimited freedom for the security provided by government, yet it was the people of the state that held the ultimate power throughout. An elected body of government protected the rights of the people, and all people deserved the right to freedom, freedom of speech and religion. These ideas may have influenced Thomas Jefferson as he drafted the Declaration of Independence. Rousseau’s ideas also shaped some of the narrative of the beliefs held by French revolutionaries as well.

This snapshot of a few of the prominent names of both the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution show the theories discussed on the European continent in the age of revolutions. These ideas of liberty and individual rights inspired revolutions, such as the American Revolution in 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789 along with other uprisings such as in Poland in 1794. Their names and ideas still have relevancy through the ages. For example, the ideas of Adam Smith are still discussed in modern capitalism today, and his work is still listed as required reading in economic classes in universities around the United States and world.

By the end of the Age of Enlightenment a “new sphere” of political debate was evident in Europe and a sense of individualism among the populace prevailed. The explosion of literacy and culture of reading and debate in society also increased. This fueled notions of the concept of liberty and freedom. Science, industrialization and economic growth of the 18th century were propelled by the ideology that emanated from the Age of Enlightenment. These ideas though did not remain on just one side of the Atlantic Ocean.