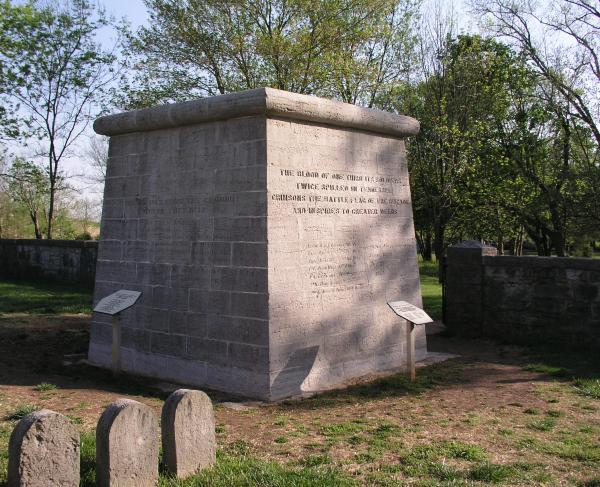

James McCloughan at Stones River National Battlefield, Murfreesboro, Tenn.

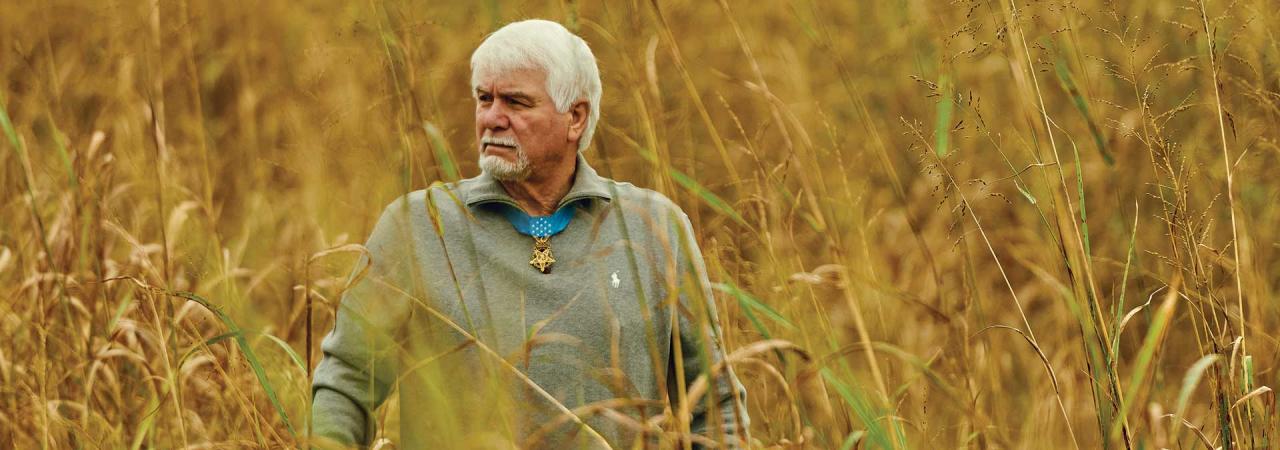

I graduated from college on June 4, 1968, and had just signed a contract to teach and coach at South Haven High School in Michigan, where my dad had graduated from in 1941. And in the middle of June, got a letter from an uncle of mine, Uncle Sam, who wanted to see if I was physically fit. I really didn’t think it was anything more than that. But in July, I took that physical and I said to the lady, “Well, what’s next?” She says, “You don’t know? You’re getting drafted.”

Out of my about 250-man basic training, I was the only one to go to Fort Sam Houston to study to be a medic. I think someone looked at the college classes that I’d taken studying to be a coach — kinesiology, physiology, anatomy, first aid, advanced first aid, strapping and taping — and they thought they gave me a step up.

The first day I was in Vietnam we hit an ambush; I had two wounded in action, two killed. And I killed my first enemy soldier.

The Vietnam War was the first time that medics actually carried a rifle, even if I gave it up most of the time because I needed both hands. But that day I used it, and I was frozen in place when I shot this human being and watched him flip in the air and die. My sergeant saw how that had stunned me, and he slapped me and said: “Doc, that’s the way it’s going to be. Do you understand? It’s either going to be you or him.”

In Vietnam, when I heard “Medic!”, that was my cue. Maybe they were dead by the time I got there, maybe they were wounded badly; maybe I can’t move them. What do I do? To make those kinds of judgments in a split second, when life and death is inevitable, is not easy. But I knew my job: I was a combat medic, and when I was called, that meant someone needed me.

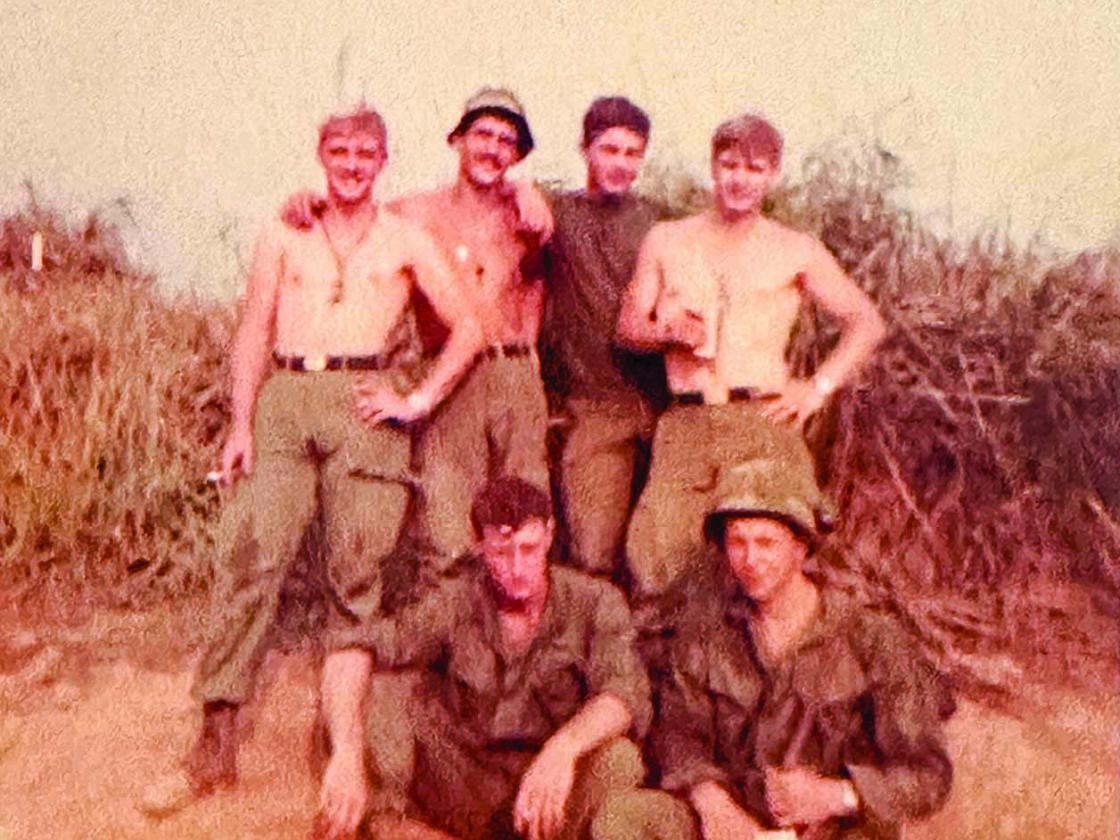

On May 12, 1969, battalion headquarters decided to send Charlie Company into the Tam Kỳ area near the foot of Nui Yon Hill. It was a flawed mission where 89 men went up against 2,700 enemy soldiers. Upon approach, two helicopters were shot down. Because it was a hot LZ (landing zone), we were forced to jump from the helicopters with our packs, weapons and ammunition. Quite a few were injured in that process; one I rescued in a fireman carry, swerving so I’d be a moving target. I could hear and see the bullets skipping off the ground next to us, but we didn’t get hit at all.

At four o’clock, my platoon set out. We were going down a trench line, left by the French in the French Vietnamese War, when all hell broke loose. I looked up over the berm towards Nui Yon Hill, and there were so many of the enemy they looked like lava coming down the hill.

I heard somebody yell, “Medic!” and I handed off my weapon, told them to cover me and started off. There was an explosion behind me, a rocket propelled grenade. The shrapnel stung as it pelted my body from top to bottom, but I concentrated on what I had to do.

I went out four or five more times that night. When the enemy backed off, we were able to get a medevac in to get out all the wounded and dead within our perimeter. Lt. Carrier said, “Get on, Doc,” and that’s when I remember I had gotten hit. I had my own blood all over me, but I remembered what I’d seen on that hill and said, “I’m not going. You’re going to need me.” I thought, by refusing to get on that helicopter that I’d just spent my last day on Earth. But I’d rather be dead in a rice paddy than alive in a hospital to find out that the next day my men got killed because Jim McCloughan wasn’t there to do his job.

That night, I got an AK-47 round in my forearm and closed it up with only two stitches to save supplies. Two of my worst wounded happened - one in the shoulder and a stomach wound where the organs were starting to come out. I got pressure bandages on that, and was using my water to wet them down, otherwise the organs would dry up and he’d die anyway. I dragged him very gently and slowly into a trench line thinking to myself “How am I going to carry this guy out of here?” If I throw him over my shoulder, everything I did was going to come undone. So I decided I’d cradle him like a baby up against my chest and hold his organs in place with my own body.

Ultimately, I got everybody loaded and I started back towards where my weapon was, but the next thing I remember was waking up in an aid station with two IVs in me. I’d had nothing to eat or drink for those two days, so I was dehydrated and probably 15 pounds lighter. I got disconnected and found my backpack. They told me I had to stay put, but I said, “The hell I’m not!” and rejoined my team out in the field. I’d been wounded three times by the time I got an invitation to join 91st Evacuation Hospital as a liaison some months later. It was one of the hardest things that I ever had to do to leave my guys.

Of the 32 who marched away from Nui Yon Hill, I’ve reconnected 23 of us. When I find them, I’ll say, “This is J. McCloughan” but that doesn’t always mean much. When I tell them, “This is Doc,” they know in an instant. At the ceremony where I received the Medal, there were 10 men there who were in my unit, five of whom I had saved in the battle - plus the son of another who had passed away.

Read James McCloughan's Medal of Honor Citation

Of the 32 who marched away from Nui Yon Hill, I’ve reconnected 23 of us. When I find them, I’ll say, “This is J. McCloughan” but that doesn’t always mean much. When I tell them, “This is Doc,” they know in an instant. At the ceremony where I received the Medal, there were 10 men there who were in my unit, five of whom I had saved in the battle - plus the son of another who had passed away.

In that battle alone, I saved 10 Americans, and one Vietnamese interpreter from being either killed or captured. But it’s more than one life that gets impacted. I got a letter in June 2019 that said, “You don’t know me, and I don’t know you, but you saved my grandpa in 1969. My mom was born in 1970, and I was born in 1991. Last week my wife and I had a baby boy, and this Sunday, I get to celebrate Father’s Day because of you.” I read that to my wife, Cherie, with tears in my eyes and she said, “Jim, you didn’t save 11 people, you saved 11 family trees.” That’s what all of those who have fought for and will fight for our freedom do, they save family trees so that generation after generation will have the luxury of being born as an American.

Chaplain John Whitehead didn’t have a helicopter to come in with when he and the 15th Indiana were at the Battle of Stones River in December 1862. He had less medical training than I did, and in the Civil War battle with the highest casualty percentage, he just hoped he could get the wounded somewhere safe. He went forward to the front and helped the wounded and the helpless — without any gun — setting his emotions aside to perform this act of being an “angel.” The wounded, they scream for help, and I know how he felt when he responded. He was clear back in the 1860s and here I was in 1969, but I know what John Whitehead was facing because I was there. I did the same thing that he did, only a hundred years later.

Read Chaplain John M. Whitehead's Medal of Honor Citation

There were occasions where I knew I wasn’t going to save that person, boys I held in my arms to hear their last words and see the last breath of life come out of their body. I know that the freedoms that we have day-in and day-out have been paid for in full. John Whitehead knew that, and Jim McCloughan knows that.

It’s still hard to think back on, so I put it in the back of my mind for so many years. When he came home after his battlefield experiences, I’m sure John had the same difficulties that I have. There were times when you would cry. There were times when you would feel as if maybe I could have done more. It stays with you for the rest of your life. I’m sure that John Whitehead, though, being a man of the cloth, felt the Holy Spirit say, “John, you did well. You did what you could do, and you’re okay.”

The brotherhood between veterans is why the Grand Army of the Republic was formed after the Civil War, but that connection exists among all veterans of all wars, from then forward to my grandpa’s World War I and my dad’s World War II, to my uncle Wayne in the Korean War and my uncle Jack in the Coast Guard and beyond. I’m sure there was PTSD amongst all those eras, too, they just didn’t call it that at the time. Brotherhood can save you. I only went for counseling after I quit teaching and coaching, when I was less busy and things started flooding back. My counselor was a Marine paraplegic in a wheelchair, who knew the right questions to ask, to bring out what was still hidden deep inside me.

When I learned about John Whitehead, I could see things that he and I did that were parallel. If I could go back in time and meet John Whitehead, I would thank him for being him, for laying his life on the line for the freedoms that we enjoy here today. It took his fortitude, it took his compassion, it took his kindness, his love for his country and what he wanted this country to be.