On April 12, 1862—exactly one year after the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, started the American Civil War—a daring raid plunged Union operatives into the heart of the Confederacy in an effort disrupt transportation and communication lines. Andrews’ Raid ended disastrously but had several significant outcomes: surprising the Confederacy, inspiring the first presentations of the Medal of Honor, and sparking persistent adventure tales for Civil War memory and pop culture.

By the early spring of 1862, Union armies advanced into Confederate territory. General Ulysses S. Grant had captured Forts Henry and Donelson in February while General Don Carlos Buell seized Nashville, Tennessee’s capital. In the eastern theater, General George B. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac transferred to the Virginia Peninsula, beginning their slow march toward the Confederacy’s capital, the city of Richmond. The Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7 resulted in a Union victory in western Tennessee and shockingly high casualties for both sides.

James J. Andrews, a former house painter and singing coach from Kentucky, had volunteered as a civilian smuggler, secret agent and scout, working for General Buell in Tennessee. For some time, Andrews had been wanting to take war deeper into Confederate territory and cause disruption of their communication and supply lines. He planned a raid that would take a small group of men to Atlanta, Georgia, steal a locomotive and wreck track, bridges and telegraph lines as the train chugged northwest through Georgia toward Union lines. This first plan sputtered when the engineer to drive the captured train failed to show up at the secret meeting place. Undeterred, Andrew revisited the plan as Union General Ormsby M. Mitchel threatened Chattanooga, Tennessee. This time Andrews proposed to steal a train in Georgia and head north toward Chattanooga, destroying whatever he could of the track and Confederate communication lines and, most importantly, the railroad bridge crossing the Tennessee River at Bridgeport. General Mitchel recognized the potential destruction of the Western and Atlantic Railroad and the morale punch that such a raid could deliver to the Confederacy and approved the operation.

By April 7, 1862, Andrews and another civilian, William “Bill” Campbell, had gathered 22 volunteers from three Ohio infantry regiments and put the plan for this second raid into motion. Dressed in civilian attire, they journeyed south into Georgia. Two of the volunteers were captured along the way, and two others accidentally slept in on the morning of April 12 and literally missed the train that the rest of the raiders boarded at Marietta.

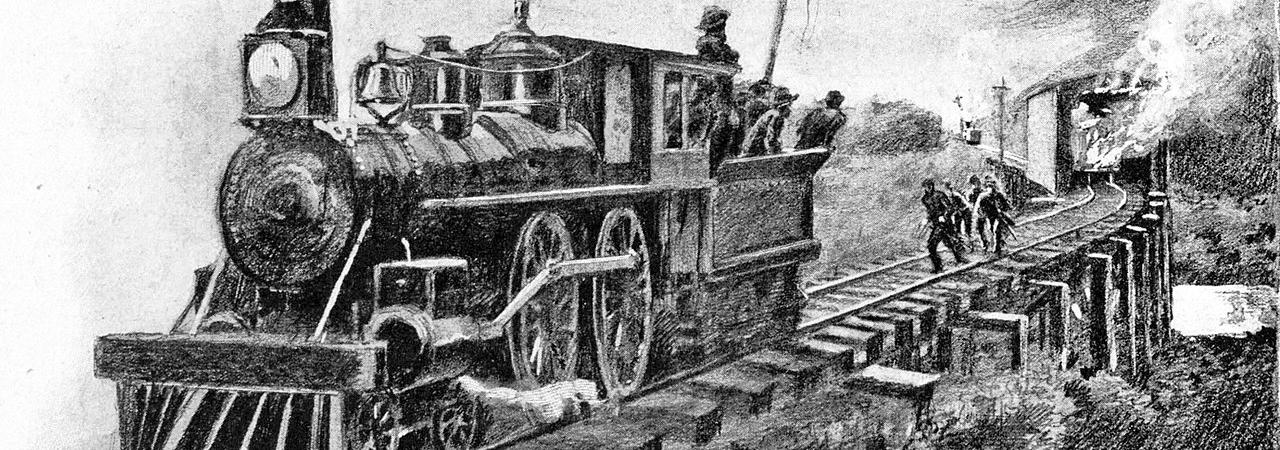

When the northbound train pulled into its stop at Big Shanty, near Kennesaw, Georgia, Andrews and his men put their plan in motion. Big Shanty did not have a telegraph office and had been previously selected as the ideal location for the takeover. While the crew and passengers breakfasted at a nearby establishment, Andrews and the volunteers unfastened most of the railroad cars and steamed off with the locomotive—named The General—a tender and three empty boxcars. Three Southern railroad men immediately pursued the “runaway” train. The chase had begun and would last 7 hours and cover nearly 90 miles of track.

The General chugged along with Andrews’ volunteers cutting telegraph lines and attempting to destroy track in its wake. At Etowah Station, the pursuers climbed aboard a locomotive—the first of three they would use in the pursuit that day. Initially, the Southerners thought that Confederate deserters had stolen the train, but eventually they discovered the Union threat and brought more Confederate soldiers into the chase. As the hours passed, Andrews’ Raiders tried a variety of delaying tactics to slow their pursuers, including uncoupling the empty boxcars, speeding along the track, and attempted destruction. The Confederate pursued closely followed and prevented the General from taking on the proper amounts of water and wood. Andrews’ men attempted to burn the bridge over the Oostanaula River near Resaca, Georgia, but the effort failed, leaving the crossing intact.

Finally, in the early afternoon, The General ran out of steam, about 2 miles north of Ringgold, Georgia. Andrews and the other raiders attempted to flee into the countryside, but Confederate pursuers—now aboard the locomotive the Texas—jumped off and followed. All of Andrews’ Raiders were captured, and the chase made exciting headlines in newspapers across the South. Eventually, 8 of the 20 captured raiders were tried as spies and hanged, including James Andrews, the mastermind and leader. (Andrews and other executed raiders were eventually buried in Chattanooga National Cemetery.) The other twelve men either escaped or were eventually exchanged.

Andrews’ Raid did not produce long-term disruption to Confederate transportation or communication. The Confederates quickly repaired the cut telegraph lines and missing railroad ties. General Mitchel did not march toward Chattanooga, and that city and railroad hub remained in Confederate control until November 1863. The raid created sensation and exposed threats to railroad lines but had little other military effect in 1862.

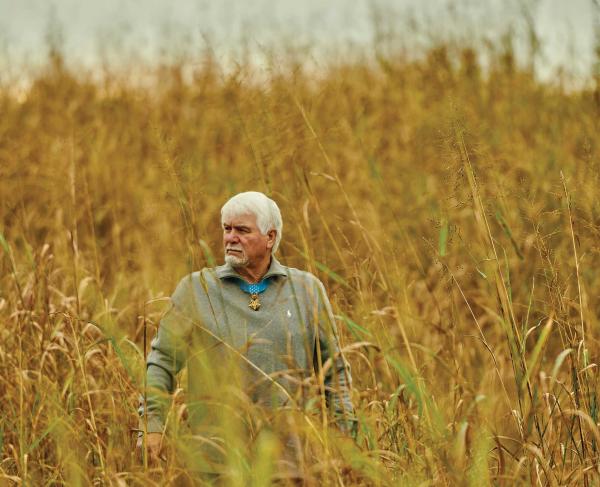

The presentation of the first Medal of Honor on March 25, 1863, to Jacob Parrott—one of Andrews’ Raiders—placed the incident in United States military memory. Five other raiders also received the Medal of Honor that day. In total, 21 of the 24 participants in Andrews Raid eventually received the Medal of Honor, some in September 1863, some after the war, and some posthumously. As civilians, James Andrews and William Campbell were not eligible to receive the Medal of Honor.

In the post-war years, participant William Pittenger published several volumes about the raid, highlighting the thrilling aspects of the locomotive chase and making popular reading material. The story of Andrews’ Raid made its way to the film industry. Edison Studios—brainchild of inventor Thomas Edison—produced The Great Train Robbery in 1903, loosely inspired by incidents from 1862. Railroad Raiders of ’62 in 1911 brought 12 minutes of film drama to the screen, including many fictional additions. In 1927, the silent comedy film The General starring Buster Keaton made its debut with fame and wildly hilarious inaccuracies. A few decades later in 1956, Walt Disney produced The Great Locomotive Chase, keeping the story alive in history’s popular memory.

Although Andrews’ Raid did not have the long term military effects that its planners had anticipated, the incident holds a place in Civil War memory and is remembered as military adventure and sacrifice that led to the first presentations of the Medal of Honor.

Further Reading:

The Great Locomotive Chase: A History of the Andrews Railroad Raid into Georgia in 1862 by William Pittenger (1917).

Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and The First Medal of Honor by Russell S. Bonds (Yardley: Westholme, 2007).