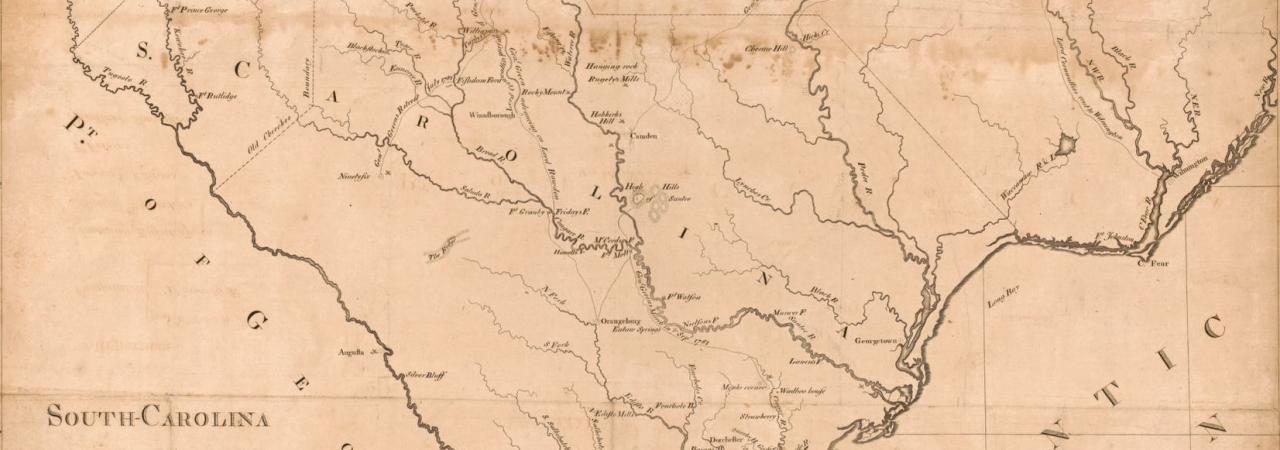

Map of the State of South Carolina showing the movement of the American and British troops during the American Revolution.

Fishing Creek

Battle of Catawba Ford, Sumter's Defeat

Chester County, SC | Aug 18, 1780

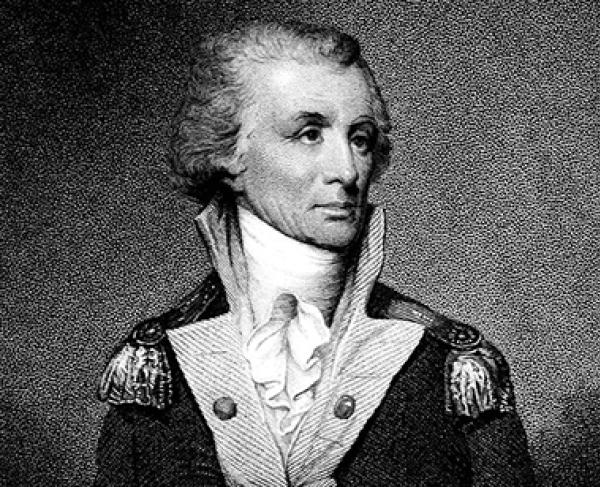

Two days removed from the disastrous defeat at Camden, the Continentals lingering in the South Carolina countryside were considering their options. Continental Major General Horatio Gates had already departed the state on his infamous ride to safety at Hillsborough, North Carolina, which costed him his reputation and command of the army. The American forces that ran from the field at Camden had scattered into the swamps and hills doing their best to remain out of sight of British patrols looking for would-be prisoners. As these days unfolded, the lone promising result of Gates’ last orders prior to Camden would be the target of the British General Charles, Lord Cornwallis’ most fearsome field commander.

Prior to the Battle of Camden, under orders from Gates, Brigadier General Thomas Sumter’s force had captured Fort Cary on the Wateree River near Camden and proceeded north up the west side of the Wateree and Catawba Rivers. In his possession were the captured bounty of fifty British supply wagons, three hundred head of cattle, and two hundred-fifty prisoners. After the Americans crumbled at Camden, Lord Cornwallis’ main army waited at Rugeley’s Mill for Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion to return from its pursuit of stragglers. British Lieutenant Colonel John Turnbull and Major Patrick Ferguson hovered on Little River to cut off Sumter’s movement. Early in the morning of August 17, Tarleton led his Legion up east of the Wateree to overtake Sumter’s partisans. After an exhausting march, Sumter’s column reached his Rocky Mount campsite on the 17th. Sumter knew he had eluded Ferguson and Turnbull, but was unaware of Tarleton. The Legion’s commanding officer pushed his mixed force of light infantry and cavalry in covering thirty miles, bringing him across the Catawba River opposite of Sumter. He briefly waited to ambush the partisans, anticipating they would cross the river near Great Falls. The American campfires could be seen from the across the river. By now, Sumter learned Tarleton was opposite the Catawba and marched further north several miles above the mouth of Fishing Creek the morning of August 18. The march in the summer climate had been brutal on Sumter’s men. The commander called a halt to his column and allowed his force of one hundred regulars and about seven hundred militia a few hours of rest. The Continentals stacked their arms, and the men bathed in the river, slept, and strolled to nearby plantations. For his part, Sumter lay partially undressed under the shade of a wagon, deciding to nap after posting two sentries to the south of the camp.

Sumter felt confident Tarleton was far enough away, and that the Catawba River provided safety to unfetter his camp in such a condition. Had Banastre Tarleton been another type of commander, Sumter’s assumption might have been correct. But Tarleton, whose reputation was growing, was a relentless pursuer of the enemy. The harsh climate had slowed his progress too, but instead of resting, Tarleton cut loose most of his light infantry and artillery, refitted with 100 Legion dragoons and about 60 infantry doubled up on the horses, and continued his advance by crossing the Catawba River. Now, with ravines to the north and the south, Tarleton closed in on the American camp. Pausing on a slope overlooking the camp, he could see the stacked arms unguarded within the camp.

Captain Charles Campbell led Tarleton’s advance guard, alerting Sumter’s sentries who shot and killed one of the Legion dragoon. Infuriated, the remaining British dragoons rode forward and hacked them down with their sabers, much to displeasure of Tarleton, whom wanted a prisoner to interrogate. Sumter had been awakened by the sentries’ muskets, but was told by a soldier it was likely militia firing at wandering cattle. However, Colonel Edward Lacey heard the shots and ordered his men to huddle behind the baggage wagons to post effective resistance. Colonel Thomas Taylor had just removed his boots, preparing to lie down and rest when Tarleton’s horsemen suddenly appeared. Samuel Martin wrote that Sumter had ten companies of militia and “the men were engaged in drinking, having taken two hogsheads of rum from some Tories who were conveying it to the British … Many of the men were so drunk that they couldn’t succeed in stopping Tarleton.” Tarleton formed a single line on his approach as the British charged into the camp. The green-jacketed horsemen cut to pieces the few able-bodied Americans who raised musket and sword to defend the camp.

Elizabeth Peay “saw Tarleton’s men cutting down the Whigs and she grew faint and sick, until she heard the bullets whistling past her and breaking limbs. She lay down beside the log, pulling her children down beside her.” Patriot Captain James Pagan called to his company to rally behind a fence, but when the British Legion charged down upon them, his company fled, and Pagan was sabered by the dragoons at the fence. Some of Colonel Woolford’s Marylanders tried to get to their stacked weapons but they, too, were cut down. Woolford was “badly wounded four times.” Sumter’s artillery was able to fire one shot but then was overrun. The camp was in complete disarray with loose horses running in every direction and dozens of Americans diving into the Catawba River. American Richard Winn wrote, “Many of the men who were swimming were called upon to surrender, with the promise of good treatment and upon emerging from the stream were mercilessly cut down by the enemy.” Sumter, who had escaped the camp shoeless and half-naked, was picked up by Captain John Steele and carried to another horse. Riding nonstop, Sumter reached the American Major William Richardson Davie’s camp at Charlotte, North Carolina, two days later.

The sheer feat of Tarleton’s attack cannot be understated. Facing a superior force of nearly five-to-one against him, he nevertheless completely destroyed Sumter’s force and rescued the British prisoners of Fort Cary and the entire confiscated baggage train. Tarleton had lost nine soldiers, including Campbell of the 71st Highlanders, an officer who had burned Sumter’s home several months before. The Americans lost one hundred fifty and another three hundred were captured along with additional wagons, the artillery pieces, eight hundred horses, and one thousand weapons. James Colvin wrote, “The dead and wounded lay scattered in every direction over the field; numbers lay stretched cold and lifeless; some were yet struggling in the agonies of death, while here and there, lay others, faint with the loss of blood, almost famished for water, and begging for assistance.” Perhaps the only positive story to come of the affair was the daring escape of Americans Lt. Col. Henry Hampton and Col. Thomas Taylor, both taken prisoner by Tarleton, who cut through their rope-tied hands with a pocketed knife, and fled into the swamp.

Sumter’s defeat at Fishing Creek on August 18 crystalized the finality of Gates’ debacle at Camden on August 16. In a matter of four days, what promise there was of American manpower and military backbone had been routed in the most humiliating way. The skirmish at Musgrove Mill on August 19 proved to be the only thing keeping the local revolutionary hopes alive in the unforgiving South Carolina summer of 1780.

Related Battles

800

160

460

15