American Dogs

We all know that dogs are man's best friend. In wartime, dogs would help hunt and act as couriers but they also provided a much-needed morale boost to the homesick, injured, and disillusioned soldiers.

George Washington, Canine Enthusiast

George Washington is more than just the Father of Our Nation, he is also the Father of the American Foxhound. As an avid dog lover and fox hunter, Greyhounds, spaniels, terriers, newfoundlands, briards, and many toy breeds could be found in Washington’s extensive Mount Vernon kennel. This was not purely a working relationship though, as Washington would visit his kennels daily and provided his pups with creative names, such as Madame Moose, Drunkard, Vulcan, Taster, Duchess, and Truelove. His favorite companion was a little staghound named Sweet Lips, who accompanied him into battle and the First Continental Congress in 1774.

Washington was also an expert breeder. After receiving dozens of great gascony blues and french foxhounds as a gift from Marquis de Lafayette, Washington began crossing the gifted canines with existing American breeds, leading to the rise of the American Foxhound—a smarter and faster variant of its French and British counterparts. The breed was officially recognized by the American Kennel Club in 1886. The American foxhound is now the official state dog of Washington’s home state of Virginia.

Washington’s love for his four-legged friends carried over to the Revolutionary War. At the Battle of Germantown on October 6th, 1777, fog blanketed the fighting troops, causing mass confusion and many accidental misfires. British General William Howe’s pet fox terrier, Lila, was one of the many lost in the confusion. Disoriented, Lila followed Washington and the Continental Army home from the battle. After Washington identified Howe as Lila’s owner from her collar he felt it was his duty to return her, opposed to keeping her as a trophy of war. He delivered the dog back to Howe along with the following note, likely written by aide-de-camp, Alexander Hamilton:

“General Washington's compliments to General Howe. He does himself the pleasure to return him a dog, which accidentally fell into his hands, and by the inscription on the Collar appears to belong to General Howe.”

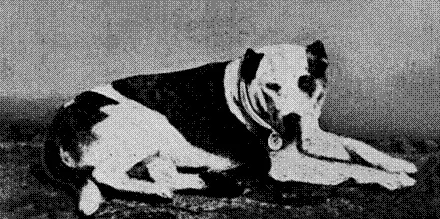

Union Jack

The 102nd Pennsylvania had a cuddly canine mascot through their time fighting in the Civil War. Union Jack was a great comfort to the soldiers and fought alongside them during the battles of Spotsylvania and Petersburg. Jack was fearless and known to always hop up to the front lines, understand bugle commands, and only obey the orders of his regiment. Jack was captured twice by enemy troops and sent to a Confederate prison, where he provided comfort to prisoners of war living there. The regiment’s love for Jack was proven when they exchanged a Confederate prisoner to get him back.

Their adoration for Jack didn’t end there. They commissioned a portrait to be made of him, which now hangs in the Soldiers & Sailors National Military Museum & Memorial in Oakland. However, Jack disappeared in Fredericksburg, Maryland. It’s suspected that his silver collar attracted thieves, or that he suffered from fatal wounds and escaped in a nearby wooded area to die.

Charles Lee

The eccentric General Charles Lee was incredibly fond of his dogs and was known to have a canine companion by his side on most occasions, even while heading to war. This propensity did not go unnoticed, John Adams once remarking, “you must love his dogs if you love him.”

Lee’s favorite pup was a Pomeranian named Spado—also known by Spada or Mr. Sparder. Lee had unusual rules for Spado, including not allowing him to eat bacon for breakfast “lest it make him stupid.” At a dinner party in 1775, Lee trained and instructed Spado to climb up on a chair and extend his paw out for Abigail Adams to shake. She recounted the event in a letter to John Adams, stating that Mr. Spader ‘has rendered famous.'

Emeline Pigott

Espionage was commonplace during the Civil War, however, Emeline Pigott’s techniques were particularly unique. At the outset of the war, female spies would use their large hoop skirts to hide important documents and materials. As commanders became aware of this tactic, they required the voluminous skirts to be searched if a woman was passing through their lines, eliminating this hiding spot.

On one occasion, Pigott, a Confederate spy, was on a mission to deliver important information about plans from nearby Union troops to Confederate General Pierre Gustave T. Beauregard. Her skirts were searched, nothing was found, and she was allowed to pass without incident. Upon arriving in the Confederate camp with her lapdog Pigott asked a soldier for a knife, which she plunged into the little pooch’s side. Beauregard and the surrounding soldiers were horrified at this assault on a beloved pet, and yet the dog remained unphased. Pigott revealed her deception as she cut away a patch of fake fur she had sewn around her companion’s middle and handed Beauregard the documents contained within it. As it turns out, man’s love and trust of dogs proved useful in this case and detrimental to the Union.

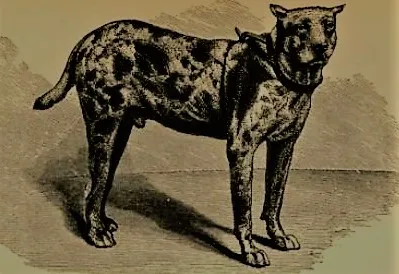

The Canine Prison Guards at Andersonville

Dogs were also used as prison guards at Andersonville Prison, a Confederate POW camp located in Andersonville, Georgia. Prison warden Captain Henry Wirz trained his “Hounds of Hell” to chase after prisoners trying to escape. The dogs were vicious and merciless, severely maiming or killing escapees. These dogs were giants, one specimen was recorded as being 198 lbs and 7 ft long. Wirz was later hanged for his role in the murder and maltreatment of several Andersonville prisoners.

Dogs served in a wide variety of roles in American history, from spies to loyal companions to disciplinarians. Through all of this, it’s safe to say that the history of these canines is a wild one.