The American Irregulars

Robert Rogers’s Powder Horn. Created June 3, 1756 by John Bush at Fort William Henry, N.Y.

Today, the Rangers of the U.S. Army may be just one of many elite forces from around the world, but they have a special place in the annals of military history for their pedigree dating back to the colonial wars, giving them a distinctively American character. While the modern Rangers cannot claim uninterrupted service, they are the spiritual heirs of irregular troops raised for the unique conditions of American warfare.

In some ways, the origins of the Rangers can be traced back to 1609. That summer, a mixed war party of Montagnais, Algonquin and Huron warriors from the St. Lawrence Valley entered Lake Champlain to engage an enemy force of Mohawks to the south. The campaign was just one small part of a longer series of conflicts between indigenous powers in North America, but this operation stands out, because accompanying the Canadian war party were three Frenchmen. This included Samuel de Champlain, the leader of the French colonizers who had established a post at Québec just the previous year. Despite technological advantages, the French colonists were far weaker than the surrounding Native peoples and understood that alliances were vital to their own survival and the profitability of the colony.

Champlain’s Frenchmen joined the Native war party to cement their alliance and counter the serious threats from the powerful Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, perhaps the most powerful political and military power on the continent. When the Canadian party formed to meet the Mohawks in battle on the lake shore near modern Ticonderoga, New York, Champlain stepped forward to fire his arquebus, unleashing a destructive new power that shaped the future of North America.

Native warriors realized their traditional weapons, armor and tactics were obsolete and quickly adapted to the introduction of firearms. Leveraging colonial powers against each other to secure guns and ammunition, Native warriors combined these new weapons with innovative tactics to subdue their enemies and counter the threat posed by European invaders. Learning how to load and fire guns with skill and accuracy, to lay ambushes and to disappear when counterattacked, Native warriors not only survived the trauma of colonization, epidemic disease and warfare, but also held off the more populous Europeans. They ultimately developed some of the most successful tactics of the gunpowder age.

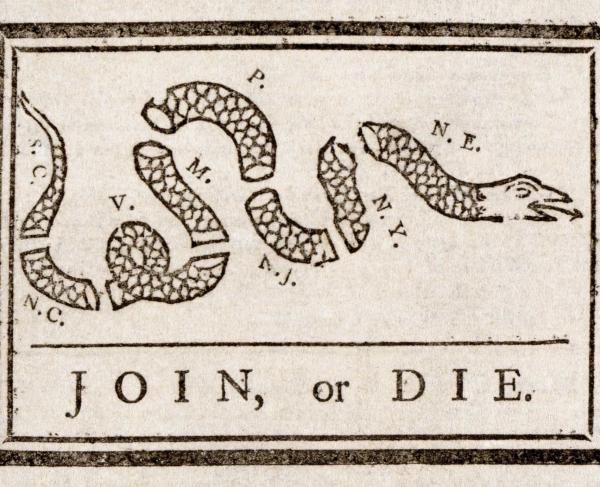

Europeans found themselves, despite their numbers and technology, regularly beaten by Natives and unable to achieve decisive victories. The tactics employed in Europe to fight against regularly equipped and increasingly professional armies were useless against this new warfare. As King Philip’s War — the conflict to which the modern Rangers explicitly trace their heritage — erupted across New England in 1675, Natives forced back European settlements up to a hundred miles. To respond, Euro-American settlers created the first Rangers. These troops were enlisted by the colonies for longer terms of service than the temporary levies from the militia and worked with allied Native Americans to learn the skills their enemies employed. Embracing these methods, Euro-American colonists were slowly able to turn the tide.

Despite their increasing competence at irregular warfare, Euro-American rangers could never fully compete at the level of Native American forces. Alliances with more powerful Native nations — including the entrance of the Mohawks into King Philip’s War —tipped the scales. To conclusively end a campaign, Euro-Americans often resorted to the cruel destruction of Native communities, killing the population and burning villages and crops.

By the mid-18th century, the concept of the ranger was well-established from Massachusetts to Georgia. The etymology of these troops also says something about their unique role. English language dictionaries from the 18th century rarely define a ranger as a soldier. Ranging or arranging was defined as the act of organizing armies, but a ranger was defined simply as one who roves, or an official who patrolled forests to prevent poaching, like a gamekeeper or game warden. This law enforcement association was an element of the ranging companies established to patrol along colonial borders (anticipating the most famous “rangers” of the 19th century, the Texas Rangers). Their name further emphasized their relative lack of strict military regulations and freedom of movement.

Most colonies lacked soldiers to defend and secure the boundaries they claimed. The militia was often too unwieldy, poorly trained and problematic to use for any extended period. A number of companies of rangers were authorized by colonial governments, giving them longer-term military forces to confront threats, particularly from Native Americans whose territory land-hungry settlers were encroaching on. In some ways, these rangers were the American equivalent of European irregular forces, such as Hungarian Hussars, Croatian Pandours, Prussian Jaegers and Highland Watches that existed as paramilitary or border forces in peacetime and were employed as light troops during periods of warfare.

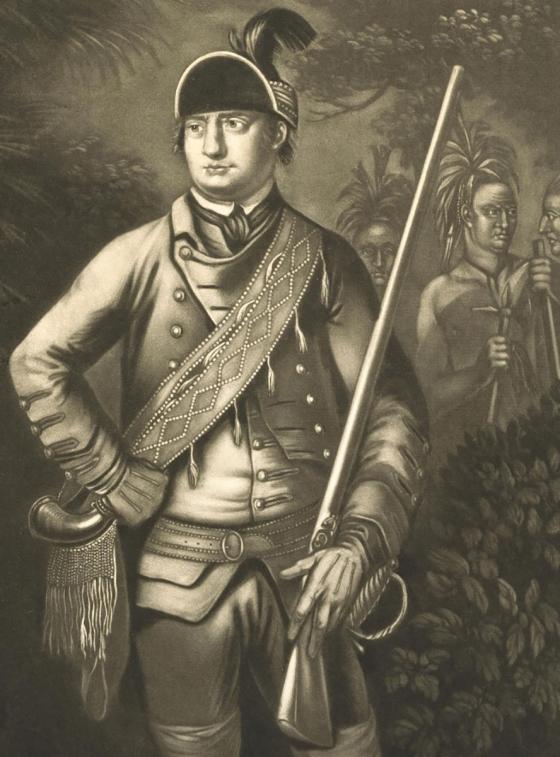

This was the case with the most famous rangers of all. Robert Rogers’s alliterative name has become so synonymous with the ranging service that it has often overshadowed the origins and context of the concept of the ranger. The opening of the French and Indian War in 1754 once again saw colonies mobilizing military forces across the continent to face the French and their Native allies. British colonists suffered early in the war from a lack of allied Natives, leaving their armies vulnerable to the hard-hitting attacks of their enemies who could also screen French forces, denying the British vital intelligence.

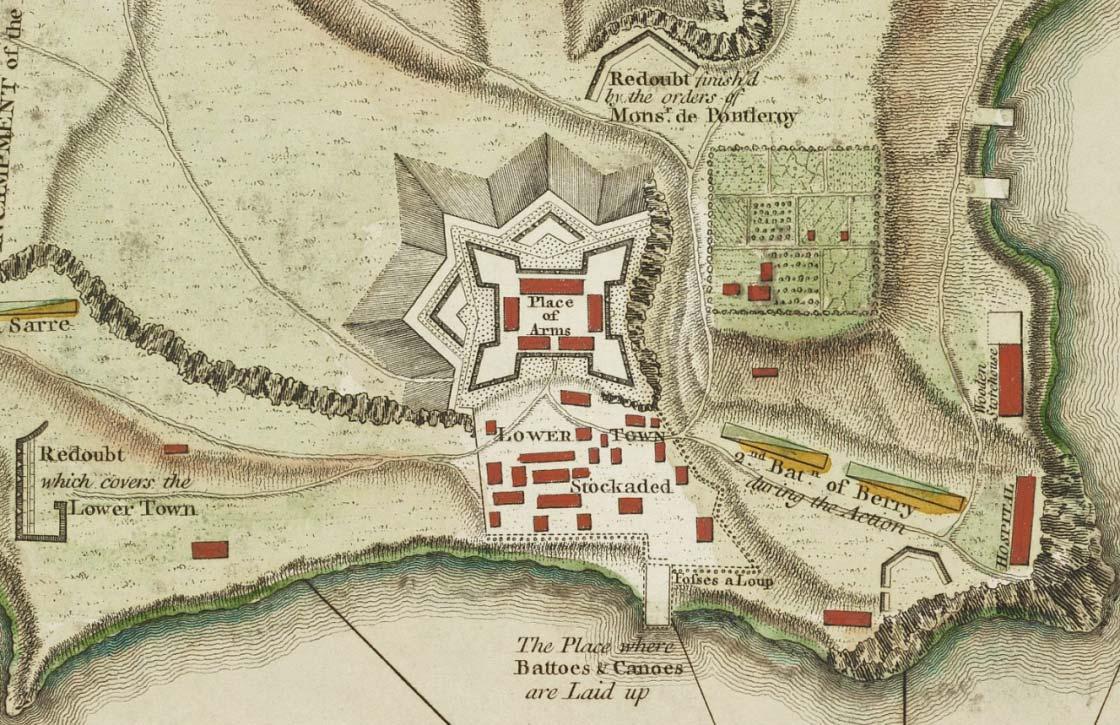

With minimal Native forces to counter the superior numbers of warriors aligned with the French, the British relied on Americans. A New Hampshire provincial captain, Robert Rogers, had impressed his superiors by scouting enemy positions and, in 1756, the British formally established an independent company of rangers under Rogers’s command. Initially a captain, he was eventually promoted to major, in command of multiple independent ranger companies. Rogers’s “created Indians” were intended to meet the Native warriors on their own terms and to act as the eyes and ears of the British Army. They provided vital intelligence to British officers about the numbers, location and condition of French and Native forces and harassed them as necessary. In battle, they acted as light infantry, whether covering the landing of amphibious forces or screening the movements of British regulars and provincials, as they did during the failed attack on the French positions on the Heights of Carillon on July 8, 1758. Rogers also trained British and Provincial officers in his unique tactics and prepared a set of 28 rules, or a “plan of discipline,” that for the first time codified in writing many of the principles of Native American warfare that Rogers had witnessed and practiced, and which are still taught to this day. An adapted version of Rogers’s Rules of Ranging has been distributed to every participant in U.S. Army Ranger School since the 1950s, and the document is considered the “standing orders” for all Ranger operations.

The rangers’ best-known operations were a series of long-distance raids against enemy positions, particularly against the French at Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga). In the winter of 1757 and 1758, Rogers’s Rangers were twice engaged in fierce firefights with French and Native forces outside the French fort, gathering information and testing French defenses. The First and Second Battles on Snowshoes, as these engagements have become known, reveal the Rangers’ ability to operate deep behind enemy lines, but not without significant danger. Rogers himself barely escaped the 1758 battle, losing many of his men in the process. These engagements also reveal the intense conditions faced by Rogers’s Rangers that rendered regular forces immobile in the depths of winter. Employing sleds, snowshoes, whaleboats and even ice skates, they traversed the wooded and inhospitable landscape of the lakes, rivers and mountains of the north.

Perhaps his most famous exploit also emphasizes the violence and ambiguity of colonial warfare. Europeans, threatened and viewing Native American ways of war as uncivilized, resorted to the same “savage” conduct they decried in their enemies. In 1759, Rogers was ordered on a bold long-distance raid against the Abenaki village of Odanak (St. Francis), which tested his troops’ endurance. Striking far to the north through forests and bogs and evading French naval forces and enemy patrols while cut off from their line of approach, Rogers executed the daring mission. However, as the Rangers sprang the trap on the sleeping village, they encountered few warriors. Like other Europeans unable to find their enemy, they set fire to a substantially built Native town, leaving the dead behind, mostly women and children.

The ranks of the Rogers’s ranger unit were surprisingly diverse. Recruited in America, colonial Americans were joined by Europeans from the British Isles, as well as continental Europe. In addition, a number of men of African descent were found in its ranks, and the Rangers operated alongside a large contingent of Stockbridge Mohicans. The confidence gained through the ranging service undoubtedly had an impact on many former members: John Stark and Moses Hazen, both former Rangers, served as Continental generals during the Revolutionary War, leading troops at Bennington and Yorktown, respectively.

The fame of Rogers and his Rangers was elevated in no small part through self-promotion. Rogers arrived in England after the war and published his own account of his exploits in London in 1765. The Journals of Major Robert Rogers solidified his reputation, and he secured a position as Governor Commandant of Michilimackinac. His actual governorship was marred by disputes and tension with superiors and subordinates, leading to a protracted court martial and imprisonment. The experience stained his reputation, and he struggled to revive his fortunes as the colonies crept toward revolution.

The extensive use of regular troops to garrison the colonies and enforce new accommodations for Native Americans after the French and Indian War decreased the need for colonial Rangers to monitor the frontier. However, Euro-American colonists increasingly grew frustrated and resentful of these forces. During the Rage Militaire that swept the colonies in the heady years preceding the American Revolution, the spirit of the rangers lived on as volunteer companies across America chose the name “rangers” to evoke these hardy American soldiers. In proposing flank troops for the militia in 1775, Timothy Pickering, a future secretary of war, gave them the denomination “rangers,” expressing a claim to a distinctively American military prowess.

Congress’s recruitment of “expert riflemen” from Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania in 1775 in some ways revived the notion of the rangers who had served during the French and Indian War as an embodied corps of light troops. The increasing American use of riflemen, a skilled minority in the Continental ranks, often replaced the use of rangers as such in the role they had made famous two decades earlier. The term was used as Pickering had suggested for some troops drafted for duty outside the line, such as Colonel Thomas Knowlton’s Rangers, who acted as light troops for Washington’s army during the New York Campaign of 1776.

The ongoing need for light troops for reconnaissance and harassment of the enemy, often employing Native experts, gave rangers a vital role in the Northern and Canadian Theaters. Captain, later Colonel, Timothy Bedel ultimately raised a regiment of Rangers from New Hampshire. One of Bedel’s officers, Benjamin Whitcomb, became perhaps the most successful ranger of the Revolution. Evading detection for days, Whitcomb scouted British positions along the Richelieu River in July 1776, when he fired on a mounted British officer. Whitcomb had, in fact, mortally wounded Brigadier General Patrick Gordon, one of the highest-ranking British casualties during the entire war, earning Whitcomb the mark of an assassin by the British. He was ultimately rewarded with a captaincy and the command of two independent companies of rangers operating out of Ticonderoga.

Despite Whitcomb’s success, the most extensive use of at least nominal “rangers” was actually by Americans on the other side of the conflict, most famously by Robert Rogers himself. Rogers actually did apply to Congress for a command among the Patriots, but was not trusted and eventually cast his lot with the British and raised a Loyalist corps called the Queen’s Rangers. Under Rogers’s management, the unit was ineffective, however, and he and many of his officers were purged. The corps was transformed into one of the most successful Loyalist units of the Revolution under the command of the Englishman John Graves Simcoe. Rogers, and his brother James, were able to raise another unit, known as the King’s Rangers. They joined a host of Loyalist light troops that sought to evoke the spirit of the Rangers, from Colonel Thomas Browne’s East Florida Rangers to the New York Rangers, a volunteer company in occupied Manhattan, to the Loyalist refugees who formed the Queen’s Loyal Rangers in the Champlain Valley. Loyalist units like Butler’s Rangers, operating out of Fort Niagara, came closest to the irregular spirit of the rangers and their cooperation with Native Americans, earning them a fearsome reputation.

By the end of the 18th century, the term “ranger” was being applied more loosely. In Ireland, the Tullamore True Blue Rangers and the Borris in Ossery Rangers were just some of the companies found in the popular volunteer movement of the 1770s and ’80s. As the wars with Revolutionary France expanded into the Napoleonic Wars, British volunteer units like the New Forest Rangers and the Cambrian Rangers joined regulars like the 88th Regiment of Foot, which, known as the Connaught Rangers, carried the name, if not the operational aspects, of the rangers forward. In America, the term continued to be used by volunteer militia companies eager to appear elite and claim the aura of the rough frontier spirit of the past.

Although true rangers were largely gone by the end of the Revolution, their spirit — independent, hardy irregulars shaped by the intersection of European technology with Native skill and adaptability — has lived on. The legacy of the original rangers is indelibly linked with the violence of imperialism and colonization, yet the ranger represents a distinctively American military type — a concept powerful enough to be claimed by Americans on both sides of the Revolutionary conflict.