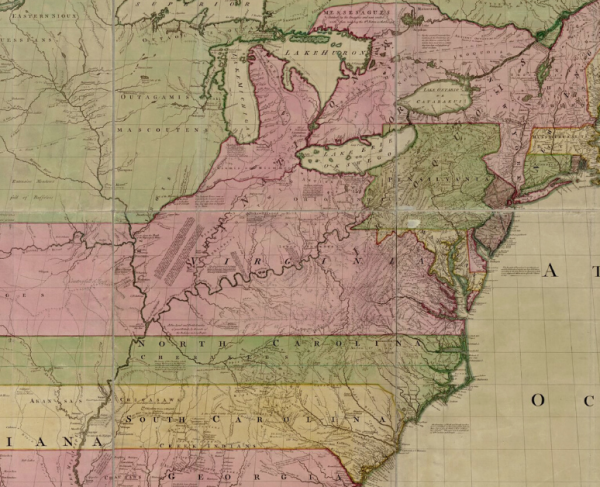

On June 8, 1775, Virginia’s last royal governor, John Murray, 4th Earl Dunmore, fled the Governor’s Palace in Virginia’s colonial capital at Williamsburg. Dunmore’s flight for safety aboard the H.M.S. Fowey, anchored in the York River, culminated a series of events that began months before. It would prove a dramatic prologue to what would happen next—a faceoff between Dunmore and Virginia patriots at the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775. When the smoke of battle cleared Virginia would join the war effort already underway in New England. Because of the events leading to and immediately after the Battle of Great Bridge, Virginia firmly embraced Revolution.

Early in the morning of April 21, Dunmore orchestrated a show of force aimed at Virginia colonists who, in defiance of his authority, encouraged independent companies to muster, and had selected representatives for the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Worse, colonial officials continued to hold extra-legal proceedings of the House of Burgesses after an angry Dunmore dissolved the body the year before in retaliation of the Burgesses’ declaration of support for “the city of Boston, in our sister colony of Massachusetts Bay,” and sympathized with Boston colonists about to feel the full weight of Parliamentary overreach with its Intolerable Acts (Coercive Acts).

With tensions already on the rise in the capital city, colonists in Williamsburg awoke on the morning of April 21 to find that in the cover of early morning darkness, Dunmore commanded troops under Lieutenant Henry Collins on the H.M.S. Magdalen, lying in wait on the James River, to march to Williamsburg’s powder magazine. There, they removed 15 barrels of gunpowder from the colony’s defensive supply. Colonists were irate.

While Dunmore was initially able to pacify colonial officials (arguing that he ordered the removal to safeguard it against a slave insurrection, a mounting threat in the region), suspicious colonists grew wearier of Dunmore’s actions, especially as news of the recent battles at Lexington and Concord reached Virginia. Prophetically, in the heat of a tense moment Dunmore allegedly uttered “I have once fought for the Virginians, and by God I will let them see that I can fight against them.” Militias and independent companies formed to the north and west, pledging their readiness to march on the capital in defense of the colony as Dunmore continued to intimidate the colonists by threatening to incite a slave rebellion against them. Learning rumors of the gathering militias and fearing for his life, Dunmore escaped aboard the Fowey and ordered its marines to march on Williamsburg. Fowey Captain George Montagu threatened to bombard Yorktown if provoked.

Dunmore received reinforcements from the 14th Regiment of Foot and support from the Gosport shipyard (present day Norfolk Naval Shipyard) which placed him in command of a veritable flotilla. Dunmore spent the rest of the summer levying a series of raids in and around Hampton Roads, confiscating a printing press, and “collecting men, provisions, warlike stores of every kind, spiriting up the back counties, and perhaps the slaves.” As Dunmore grew his own forces to put down the rebellion of patriots in Virginia, the meeting of the Third Virginia Convention in August formally authorized Colonel William Woodford, along with his 2nd Virginia Regiment and the Culpeper County Minutemen to proceed to Hampton Roads to engage Dunmore’s forces. Rumors circulated that Dunmore solicited the support of Virginia’s slaves, and that he “(had) it in his contemplation to make great use of them in case of a civil war in this province.” These rumors proved true on October 26 during the Battle of Hampton and on November 15 during a skirmish at Kemp’s Landing—both events saw runaway slaves fighting with Dunmore’s forces against the patriot militias.

With his confiscated printing press Dunmore finally manifested one of the colonists’ long-feared threats. On November 7, Dunmore issued a proclamation to the colony of Virginia. In it, Dunmore declared martial law, named colonists refusing to take up the king’s standard to be traitors, and, finally, granted freedom to “all indentured Servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to Rebels)…that are able and willing to bear Arms” with his troops. Dunmore’s proclamation and subsequent formation of his “Ethiopian Regiment” so incited Virginia’s colonists—who had long feared a slave revolt—that even those who had intended not to take up arms against royal authority were persuaded to join the patriots’ cause.

By November Dunmore commanded a force of about 175 British regulars from the 14th Regiment of Foot, 200-300 runaway slaves in his Ethiopian Regiment, and a newly-created Queen’s Own Loyal Regiment formed from approximately 600 Virginia loyalists. With this force, Dunmore went to work to fortify Norfolk and the surrounding environs, but a rumor that patriots had already garrisoned at Great Bridge prompted him to investigate.

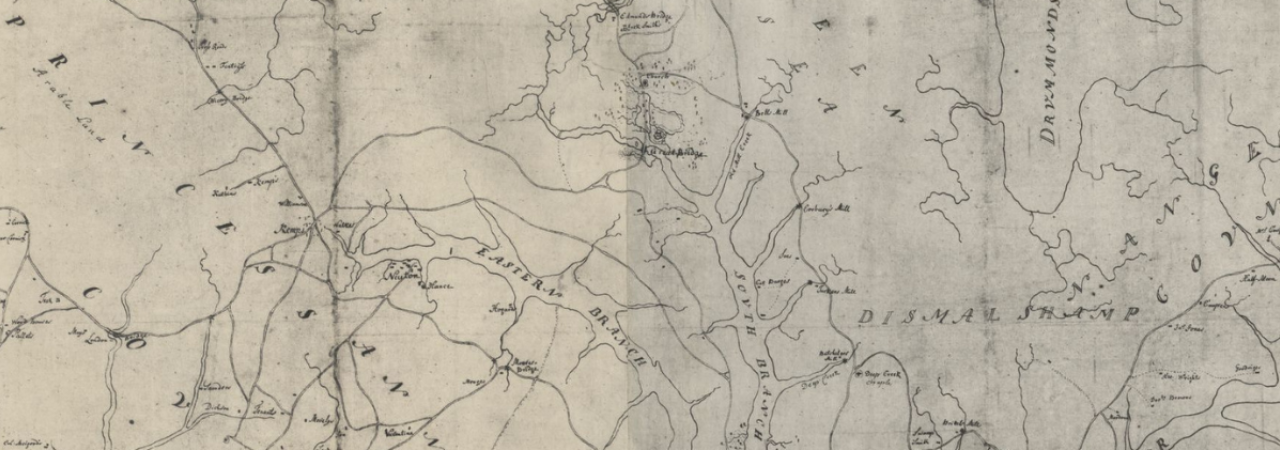

Now part of Chesapeake, Virginia, the settlement at Great Bridge was situated along the Elizabeth River and on the main road connecting Norfolk (12 miles to the north) and North Carolina (to the south). According to contemporary accounts, the original landscape of Great Bridge was difficult terrain, where “the land on each side is marshy to a considerable distance from the river, except at the two extremities of the bridge, where are two pieces of firm land, which may not improperly be called islands, being surrounded entirely by water and marsh, and joined to the main land by causeways.”

Eager to maintain this position as a supply route and finding no patriots on site, Dunmore left a contingent of men to fortify a position on the north side of the bridge. According to some sources, about 100 men (half of them members of the Ethiopian Regiment) occupied the new fort, which Dunmore’s men called “Fort Murray,” complete with two cannon to defend the Norfolk side of the bridge and causeway.

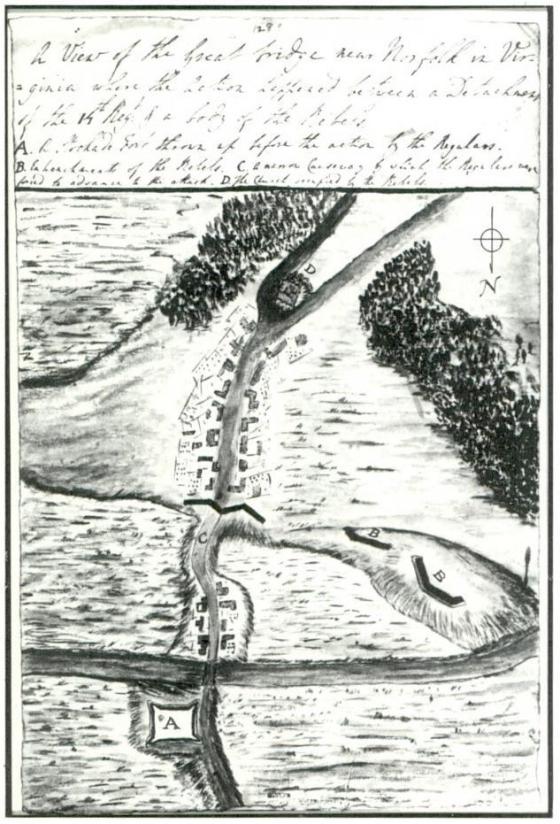

On November 15, Dunmore moved east to Kemp’s Landing, where he thwarted an ambush by the Princess Anne County Militia. Undeterred, Dunmore marched north to Norfolk, and easily took the city (already a loyalist stronghold). Hearing rumors that Dunmore planned to advance next west to Suffolk, on November 25 Colonel Woodford sent a detachment of 215 men under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Scott to engage. The patriots arrived in Great Bridge on November 28, and were immediately confronted with shots from Fort Murray, which they called the “hog pen.” The patriots entrenched along the opposite causeway, and “from the breast work ran a street, gradually ascending, about the length of four hundred yards, to a church, where (the) main body were encamped.” The narrow plank bridge connecting the two positions had since been removed. Across the formidable terrain sat Fort Murray with two 4-pound cannon, but the patriot positions were within range to attack any British movement south out of their position.

Woodford finally arrived with the 2nd Regiment and Culpeper Minutemen on December 2. Unaware of how many troops Fort Murray secured, and with a shortage of munitions (including much-needed cannon), Woodford was weary to attack. Instead, he set pickets to defend the patriot position while waiting for reinforcements and supplies. For one week the two sides played cat and mouse, taunting each other with small skirmishes within half a dozen miles from their positions along the causeway. On December 7 an additional patriot force arrived, bringing the total number of able-bodied patriots close to 900.

On December 8, Dunmore decided to break the tension. He ordered Captain Samuel Leslie’s 14th Regiment to march south from Norfolk to attack the patriot position at Great Bridge. Historians (as well as his contemporaries) debate Dunmore’s reasoning for breaking the stalemate, whether he was tipped off that patriot reinforcements were fast approaching with devastating cannon, or whether he underestimated the number (and fortitude) of Woodford’s men. Leslie arrived around 3:00 a.m. and planned a dawn attack. Even with support from 120 men from the 14th Regiment bolstering the loyalists, soldiers, and Ethiopian Regiment already at the fort, Dunmore’s force numbered half that of Woodford’s.

Shortly after the Virginians awoke on the morning on December 9, “two or three great guns, and some musquetry [sic] were discharged from the enemy’s fort” which, initially, garnered no notice from Colonel Woodford after a week of skirmishing. Altered by sights of the British replacing the planks of the dismantled bridge over the marsh between their two positions, and hearing commands for soldiers to “stand to their arms,” Woodford readied for attack. With bayonets fixed, Captain Charles Fordyce led the advance of the 14th’s Grenadiers across the causeway towards the patriot breastwork. Once the patriots became aware of the escalating situation, sentries fired three rounds to slow the British advance on the works. Famously, one of these sentries is widely believed to have been a free Black man named William (Billy) Flora who, after firing eight times into the advancing British, finally made his way to safety into the breastwork.

Once the sentries fell back Fordyce rallied his men to advance. Lieutenant Edward Travis, who commanded the patriots in the breastwork, ordered his men to hold their fire until the British came within 50 yards. Then, “the bullets whistled on every side.” Fordyce was hit in the knee, but regaining his composure waved his hat widely above his head, believing the engagement to be a swift British victory. But it was not to be. As riflemen under Woodford poured to the breastwork’s defense, carnage ensued at close range. Captain Richard Kiddler Meade of the 2nd Virginia wrote, “I then saw the horrors of war in perfection, worse than can be imagin’d; 10 or 12 bullets thro’ many; limbs broke in 2 or 3 places; brains turned out. Good God, what a sight!” Captain Fordyce lay dead 15 feet from the patriot position, his body riddled with bullets. After an unexpected barrage and their captain dead, the British faltered wildly before retreating to first to Fort Murray then, after spiking their cannon, abandoned the fort altogether and fled to Norfolk.

The British sustained heavy causalities in relation to the duration of the battle. Though the numbers vary, sources indicate that the British lost three officers (including Fordyce) and 12 privates, with 48 men wounded, among them one lieutenant and over a dozen privates who were taken prisoner. The patriots sustained only one minor casualty out of the 90 men engaged in the short battle.

Of the battle, Woodford wrote that it was “a second Bunker’s Hill, in miniature, with this difference that we kept our post and had only one man wounded in the hand.” The Battle of Great Bridge lasted no longer than 30 minutes and proved that patriots were indeed a formidable foe against British regulars.

The next day, the rumored patriot reinforcements arrived from North Carolina—regulars and militia under the command of Colonel Robert Howe. More troops continued to pour to Woodford’s aid, finally amounting to over 1,200 with which Woodford marched to take Norfolk. Finding that Dunmore had abandoned the city in favor of his floating fleet, patriots fired on the British warships, refusing them aid, supplies, or freshwater. Dunmore’s ships returned fire, eventually destroying the city.

With Norfolk destroyed (the patriots burned anything left standing so the city could never again aid the British), Dunmore moved his operations north to Gwynn’s Island, but by then disease drastically reduced his able-bodied fighting force (including the Queen’s Own and Ethiopian Regiments) to about 200 men. Realizing he had no hope left to regain control of the colony, Dunmore left Virginia and returned to Britain in July 1776.

Dunmore’s retreat after the Battle of Great Bridge ended the first British threat in Virginia. Though the colony would not be again challenged directly until 1779, the Battle of Great Bridge, and the slow-burning fuse of the Gunpowder Incident, firmly placed Virginia in open, revolutionary rebellion against Great Britain. The war had come to Virginia.

Further Reading

- A Universal Appearance of War: The Revolutionary War in Virginia, 1775-1781, By: Michael Cecere

- Dunmore's New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America - with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings, By: James Corbett Davis

- 'They Were Good Soldiers': African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783, By: John U. Rees