The Battle of Nashville

Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood began his Tennessee Campaign with lofty, if not impossible, aspirations: if he could take Nashville, — the base of Union operations in the West, he could prolong the war and force Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s recall from Georgia.

But nearly a third of Hood’s force was lost during the Battle of Franklin, offset by fewer than 200 recent recruits. Meanwhile, Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commanding the Trans-Mississippi Department, declined to send any hoped-for reinforcements to Middle Tennessee. Then, compounding his own challenge, Hood sent Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest to Murfreesboro, where the Federal garrison inside the massive earthen fort brimming with heavy guns routed his infantry. By the eve of the Battle of Nashville, the Confederate manpower barrel had run dry.

As Hood’s weary and depleted army marched the more than 15 long miles from Franklin to the Tennessee capital, their misery was only beginning. In command at Nashville was Union Maj. Gen. George Thomas, the exalted “Rock of Chickamauga.” Miles of trenches and several forts mounted with heavy guns made Nashville the second most fortified city in North America. Union gunboats controlled the Cumberland River north and east of the city. Hood sent Brig. Gen. Hylan Lyon’s troopers on a raid north of the city, but was otherwise unable to threaten the massive citadel. With few options, the Confederates dug in, surrendering the initiative.

Nor was all well on the Union side. While the Confederates entrenched, Thomas was under intense pressure, particularly from his ultimate superior Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, to attack. Recent reinforcements gave him enough manpower but, even after looking as far afield as Louisville, Ky., he lacked sufficient horses to mount his cavalry. Then there was a sudden shift in the weather to contend with, as Indian summer temperatures plummeted to near zero and several days’ worth of freezing rain, sleet and snow paralyzed Nashville. Indeed, when Union cavalry commander James Wilson moved his troopers from their camps in Edgefield, a number of his men and their mounts were injured from slipping on the ice. Grant, ignoring the weather, ordered Thomas to attack — going so far as to dispatch Maj. Gen. John Logan to relieve Thomas should an offensive not begin during the course of his journey west.

Thomas saved Grant the trouble. The weather cleared on December 14, and Thomas telegraphed his superiors, “The ice having melted away today, the enemy will be attacked tomorrow morning.” Telegraph officer J.C. Van Duzer reported that “the thaw has begun and to-morrow we can move without skates.”

Thomas’s plan was thus:; Maj. Gen. James Steedman’s ad hoc division would demonstrate against Hood’s center and right, with Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s corps in support. Two corps under Maj. Gens. John Schofield and A.J. Smith would deliver the main strike on Hood’s left, with Maj. Gen. James Wilson’s cavalry set to curl farther west around the Confederate flank. In reserve and holding the city were thousands of men who worked in the quartermaster warehouses. Altogether, Thomas numbered some 60,000 men against Hood’s paltry force of less than half that size.

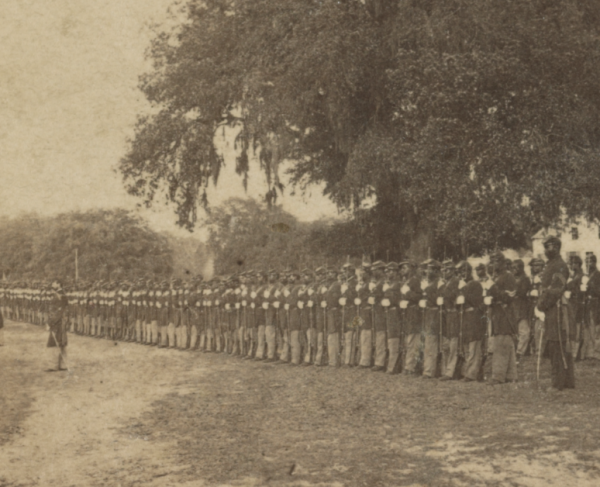

On the morning of December 15, 1864, rising temperatures created a dense fog that covered the Federal movement to their attack points. From the Cumberland River, a naval squadron of two ironclads and five tinclad gunboats maneuvered to take out pesky Rebel batteries at Bell’s Mill. At 9:00 a.m., the fog since burned off by the sun, heavy guns at Fort Negley opened the ball with a booming salvo. The Union feint, including several regiments of United State Colored Troops (USCT), moved forward. Soon after their advance, a Confederate battery positioned in a lunette along the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad opened fire, creating what Samuel Cook of the Texas unit holding the lunette deemed “a perfect slaughter pen.” The USCT men shattered limbs leaping into the railroad cut to escape, but still found themselves under a shower of Confederate rifle fire. Despite tenacious efforts to renew their advance, Steedman’s men remained stalled for the rest of the day. Hood’s right flank held; not so with his left.

Hood anchored his left with five redoubts, three close together and the other two farther afield. Each of these redoubts had been designed to hold from two to four guns supported by infantry. But on the morning of December 15, not all were finished due to lack of time, shallow bedrock and the still-frozen ground.

Into these tenuous defenses slammed Union cavalry, sending Confederate infantry rearward and capturing several wagons at Belle Meade Plantation. Cresting a rise, Federal troopers spied Redoubt Four and used their supporting artillery to bombard the Confederate works. After shelling the redoubt for a time, the Federal troopers charged, supported by Brig. Gen. John McArthur’s infantry division. “Each regiment was competing with the others to reach the redoubt first,” recalled one participant. The Rebel gunners fought tenaciously, but their fire lofted over the heads of the attackers. Soon, Union troopers from the 2nd Iowa Cavalry gained the position, forcing the defenders to leave their four guns behind. Redoubt Five was next, and the same sweeping attack soon swamped its gunners. The other three redoubts fell in rapid succession, and Hood’s left flank imploded.

Seizing the moment, Federal troopers executed a classic envelopment and rampaged well to the south behind Confederate lines. In desperation, Hood dispatched reinforcements to slow their advance. The effort weakened other parts of his line, but the risk had to be made.

Hood and his staff officers tried to rally their men along a new line about a mile to the south along the Granny White Pike. With the coming darkness, fighting died off, and the rest of Hood’s army now fell back to this second line, which actually constituted a stronger defense than the morning’s position.

This new line was shorter, which helped the outnumbered Confederates place more depth in defense, and anchored by a hill on each flank — Compton’s Hill to the west, and Overton Hill (also known as Peach Orchard Hill) to the east. Hood established his headquarters at Traveler’s Rest, on John Overton’s plantation as his ragged troops spent the entire night entrenching as best they could. Their depleted artillery feebly held the line, short 19 guns lost to the Federals that day. Meanwhile, Thomas’s army closed in the Confederates and prepared to renew the attack.

The warm sun returned on December 16, with temperatures poised to reach the mid-60s. Once again, Union artillery opened the day and the infantry moved forward. By the afternoon, the men in blue were making inroads on Peach Orchard Hill, particularly a brigade that included the 12th, 13th and 100th USCT, which gamely moved up the slope into the Rebel guns. A soldier in the 18th Alabama fumed, “To our disgust, they were all Negroes.” Five color bearers of the 13th USCT — carrying a flag emblazed with its origin: “Presented by the Colored Ladies of Murfreesboro” — were shot down before their banner was captured. The regiment lost 40 percent of its men, the highest casualty rate of the battle.

While many rank-and-file Confederates loathed the thought of armed black men, Brig. Gen. James Holtzclaw, whose brigade was causing much of their destruction, noted their gallantry in his official report before concluding that “they came only to die.” It was all for naught, however, as these Union attacks were repulsed, the units involved suffering approximately a third of all Federal casualties for the entire battle. Once again, the Confederate right held; once again, the Confederate left failed.

Compton’s Hill, which anchored the Confederate left, was so steep that, as one Federal officer observed, “[I]t was supposed no assaulting party could live to reach the summit.” As menacing as the rise appeared, it was only sparsely defended. Among those dug in was the battered division of Maj. Gen. William Bate, a shadow of its former self after severe losses in Georgia and at Franklin. At the crest were but a few artillery pieces. Hood further subtracted from these forces by transferring a large portion elsewhere. In short order, the hill was virtually surrounded, as an impetuous Union general charged it headlong without orders.

Brig. Gen. John McArthur was a fiery Scotsman and a solid combat commander. Hesitation among his fellow officers inspired him to try his luck at Compton’s Hill. At 4:30 p.m., he began an artillery barrage and then, as rain began to fall, he sent in two infantry brigades. Moving up the slopes, his men advanced at the double quick with bayonets fixed. They slowed to a walk when passing through a muddy cornfield, just as the Confederate batteries unleashed their guns. A Minnesota colonel remembered the barrage as “the most terrific and withering fire…beh[e]ld or encounter[ed].” Despite taking massive casualties, McArthur sent in his last brigade rather than halt the attack.

Thomas, seeing McArthur’s men swarm the hill, ordered a reluctant Schofield to support him. Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox’s division joined the effort now coating the hill in blue and collapsing Bate’s line. McArthur knew he had succeeded when he saw the flag of his 10th Minnesota rise above the Confederate line. Among those overrun was Lt. Col. William Shy, whose death gave a new name to what had been Compton’s Hill. Nearly killed was Sam Watkins, the famous memoirist of Co. Aytch, who recorded, “I had eight bullet holes in my coat, and two in my hand, besides one in my thigh and finger.” Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith, seeing the inevitable, surrendered only to be sabered about his head, allegedly by Union Col. William McMillen. His skull was laid open, but Smith survived, though he spent much of the rest of his life in a mental institution.

Building on their momentum, McArthur’s men turned to their left and began rolling up Lt. Gen. A.P. Stewart’s line, causing it to break and retreat in confusion. On that day alone, McArthur’s men claimed several flags and artillery pieces, plus some 1,600 prisoners. Overall, McArthur’s division took about 4,200 Confederates in the two days of fighting. Thomas famously laughed when apprised of the number of prisoners taken; these Confederates would finally reach Nashville but not in the way they intended.

With darkness coming, all Hood could do was save what was left of his army. Morale had collapsed. Fear gripped his ranks. Union cavalry sliced away at the Confederate rear, making escape impossible for some and an impetus for others. A Rebel cavalry brigade held a barricade on Granny White Pike until Union troopers crashed through it. A costly stand at the narrow Holly Tree Gap farther south allowed Hood some time to get his trains away.

Two more days of a contested retreat plus desertions carved more and more men from Hood’s once imposing army. Only Forrest’s return from Murfreesboro helped save the army from total destruction.

By Christmas Day it was over. Hood backed into Alabama having lost a third of his army in the campaign —11,823 men were counted as casualties, almost 4,500 from the Battle of Nashville alone. Also gone were dozens of artillery pieces, supply wagons, food reserves and innumerable shoes. Federal cavalry under Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson dismantled the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, shutting off supplies. For all intents and purposes, the Army of Tennessee was wrecked, and the Deep South was even more open to the Union army than before Hood’s campaign.

Despite the losses, Hood reported: “It is my firm conviction that, notwithstanding that disaster, I left the army in better spirits and with more confidence in itself than it had at the opening of the campaign.” Letters, diaries and memoirs from his soldiers demonstrate otherwise. General Thomas may have said it best when he turned to his cavalry commander and exalted, “Dang it to hell, Wilson, didn’t I tell you we could lick ‘em?”

Partner with us to save five threatened battlefield tracts representing four crucial campaigns in three states.