Was the battle of Nashville, December 15 and 16, 1864, the decisive battle of the Civil War? Similarly, was the Tennessee campaign of that fall – of which the three pivotal actions of Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville formed the key events – the decisive campaign of the conflict? Writing in 1956, local Nashville historian and student of the western theater, Stanley F. Horn, certainly thought so. He advanced the thesis in a book titled The Decisive Battle of Nashville, keying upon Sir Edward Creasy’s famous Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World. Arguing contra-factually about what could have happened had the Confederates won at Nashville, Horn asserted, “The whole aspect of the military situation would have changed.” Since then, other historians have provided more detail on the operations of November-December 1864, understandably ducking the “decisiveness” label but nonetheless tacitly underscoring what America’s preeminent military historian Russell F. Weigley reaffirmed in A Great Civil War four years ago, “Nashville ranks as probably the most complete battlefield victory of the war.” Why then has this campaign, and especially the Battle of Nashville, ranked so poorly among Civil War preservation efforts? Certainly not for lack of fine written histories by Horn, Thomas R. Hay, Thomas Connelly, James McDonough, William R. Scaife, Wiley Sword, Winston Groom, Richard M. McMurry, and most recently Anne J. Bailey, all of whom consistently emphasize one of the most under-appreciated episodes of the Civil War.

Nashville forms the culminating event of the story. Most accounts diminish its importance in comparison with missed opportunities at Spring Hill on November 29, 1864 and the insanity of Franklin, the following day. That is because the emphasis has been consistently placed upon the saga as perhaps the ultimate tragedy of the Lost Cause. The focus has been upon Confederate miscues or the inept leadership of Lieutenant General John B. Hood, commander of the Army of Tennessee, who wrecked the second most important army of the Confederacy in this ill-fated campaign. The heroic individuals whose valor and suffering resulted from the bloody slaughter at Franklin still contrast with the petulant, pain-wracked cripple who ordered it. As a consequence, however, Franklin has been allowed to obscure the cumulative event two weeks later. Other themes concerning the conclusion of war in the upper South have only lately come into their own or have as yet to be explored. While true that the Confederate side held the operational initiative in the story and it was theirs to lose, the stark fact of decisive, almost annihilative defeat of the Confederates at Nashville testifies to why survivors, veterans, and the modern South comprehensively refused to honor the significance of Nashville and the Tennessee campaign as worthy of proper commemoration and preservation. Ironically, the federal government did better by this cause, not seventy miles to the northwest of Nashville when it preserved the now-prospering Fort Donelson National Military Park, site of the initial catastrophe for Confederate arms in the west. But, it too failed through the years in its duty to set aside proper memorial ground marking the events of Spring Hill, Franklin, and especially the Battle of Nashville for study, interpretation, and most importantly remembrance.

In fact, the road to the Nashville disaster began two winters earlier when equally inept Confederate leadership, both at tactical and strategic levels, surrendered Forts Henry and Donelson to the advancing joint army-navy team under Ulysses S. Grant. Two weeks later, Nashville fell to the invaders, the first Southern state capital to do so. The city was also the commercial, industrial and social centerpiece of the region – perhaps grandiosely styled the “Athens of the South.” Gone with Nashville would be all of the upper South, especially resource-rich Middle Tennessee, with the rest of the Volunteer State following by the end of 1863. Control of rivers, railroads, farms, factories, and population centers including Nashville, Memphis, Chattanooga, and Knoxville meant that Yankee arms had captured one of the most important areas of the nascent Confederacy. The Confederacy tried for the next two years to retake the lost ground – in fact, this was what Hood’s Tennessee campaign was all about. In addition, Southern leaders and generals dreamed of wintering their armies on a frontier provided by the Ohio River. Such a dream proved impossible, but until December 1864, they never stopped trying. The Battle of Perryville, Kentucky in October 1862, the conflicts at Murfreesboro or Stones River, Tennessee at the beginning of the year, and then the Battles of Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville were all products of that dream.

Yet, at first, after the fall of Atlanta in September 1864, the Confederate strategic aims were more complex. Both Jefferson Davis and his western commander felt that William Tecumseh Sherman could be pushed back out of Georgia by a raid on his railroad logistical lifeline. Moreover, such success might also impact Northern elections (although the capture of Atlanta is now considered by historians to have been the pivotal point that convinced most Northern voters to return Abraham Lincoln for a second term). So, Hood and his recuperating army raided the railroad to little appreciable effect as Sherman bit but did not chew on the bait and Confederate attention soon shifted to the Great Dream of going north, redeeming Tennessee, and establishing a presence in Kentucky. That move might also induce Sherman’s bummers to stop raising hell in the rest of Georgia. Hood even talked of moving eastward from Kentucky to aid Robert E. Lee, besieged at Richmond/Petersburg in Virginia. The only trouble was the campaign season was fast ebbing by the time Hood and his army got their act together. Furthermore, Sherman turned his back on Hood, thinking that able subordinates like Brigadier General George H. Thomas with the corps of David Stanley and Brigadier General John Schofield could handle Sam Hood’s approximately 30,000-man Rebel host. Hood wasted most of October transferring his force from North Georgia to the jump-off area of Decatur, Alabama, only to discover a tiny force opposing his crossing that diverted his march westward to Tuscumbia. There, inadequate logistical preparation, and a delay awaiting the arrival of Nathan Bedford Forrest as reinforcement prevented departure on the northward movement before mid-November. Chilly temperatures and snow flurries indicated the lateness of the season and, possibly, the forlorn chances of accomplishing Hood’s goal before winter truly set in. Much depended upon speed, not stealth, for President Davis had already tipped off Union authorities to Hood’s plans even though he anticipated Hood would defeat Sherman before undertaking the northward move. Still, the energetic Confederate commander crossed the Tennessee at Tuscumbia/Florence and moved rapidly against Schofield and about 26,000 Federals in position at Pulaski, Tennessee, fifty-two miles to the northeast. Despite the lengthening shadows of autumn, now amply sprinkled with hail, sleet, and freezing rain, the prospects looked good for the men in the ranks singing of going back to Tennessee.

Meanwhile, if Sherman had turned his back on Hood, George H. Thomas was busy preparing to advance against him. Carefully increasing Nashville’s line of protective forts, Thomas awaited reinforcement, although by the time the Confederates headed north, the Union commander reluctantly had to direct Schofield to fall back, delaying Hood’s advance wherever possible. Still, despite abysmal road conditions, Hood nearly won the footrace to Columbia. In fact, Hood’s cavalry almost cut him off, led by the intrepid Nathan Bedford Forrest who was lately arrived from the famous Johnsonville raid. The saga of the Spring Hill affair – for it was hardly a major battle – hinged on this footrace, in essence won by Hood and his foot cavalry between November 21 and 28 when they raced past Schofield’s flanks at Columbia and then, inexplicably, failed to exploit their good fortune. Stumbling due to bungled assignments by senior leadership, the Army of Tennessee let slip distinct advantage after Forrest’s brush with a small Union force at Spring Hill. The Confederates ended up bivouacking on the evening of November 29 within shouting distance of the Columbia-Nashville turnpike whence would come Schofield and his rapidly back-peddling infantry, artillery, cavalry and wagon train. All night, as an exhausted Hood slept in a nearby house and the bright lights of Confederate campfires burned within yards of the highway, Schofield marched his army past the inattentive Southerners and on to safety the next morning at Franklin. Fuming over the debacle when he awoke, Hood berated his generals, staff, and the men in the ranks for the failure. Suitably chastened, everyone vowed to redeem the mistake. In turn, such attitudes led directly to the headlong rush to crush Schofield and resulting disaster that would be Franklin. Nobody has every satisfactorily explained the strange doings at Spring Hill. Yet, the bottom line – Schofield was saved, Hood was angered, and his army mortified – resulted in a poor circumstance under which to deliver a massive frontal assault against a waiting, well-positioned foe.

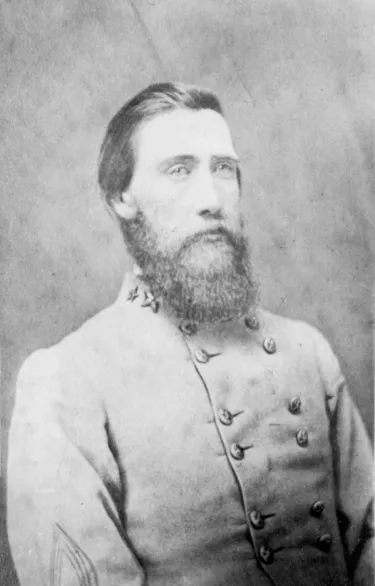

That was precisely what Hood found at Franklin. Schofield had time to prepare a position anchored on the now-famous Carter house and cotton gin just south of the village. The impact of at least a dozen gallant but ill-fated assaults initially allowed the Confederates to overrun the Federal position. Ultimately, though, the assaults only produced senseless slaughter as concentrated firepower mowed down at least 5,000 heroic Confederates (at the expense of roughly half that number of Federals), including twelve general officers and fifty-five regimental commanders. Hood had decapitated his own army by his furious attempt to salvage lost honor. His temper, plus the army’s own embarrassment over Spring Hill, wrecked the flower of the Confederacy’s western army at Franklin. Perhaps the finest fighting general in either army, Irish expatriate Patrick Cleburne, lay dead before the Union breastworks. More disheartening, Schofield simply crossed the Harpeth River that night and continued his retirement to Nashville. In a sense, the campaign was over. Yet, Hood, for one, refused to admit it. He could not, and what was he to do? Sherman was now far to the south and bent on making Georgia howl. Franklin itself offered no reason to linger. Perhaps reinforcements might come from across the Mississippi or the Federals at Nashville might decide to await spring to renew the contest. Although historians claim he had little choice, Hood did in fact have an alternative; he chose to send Forrest – not the main army – to take the fortified Federal logistical center at Murfreesboro and interrupt the Nashville to Chattanooga railroad line. It might have been better to move the diminished Army of Tennessee as a whole to take the place and they thus could have wintered somewhat comfortably, a repeat of the previous year when General Braxton Bragg had battled Major General William Rosecrans at Stones River and nearly won. Instead, Forrest failed to crack the fortified supply base called Fortress Rosecrans and whatever damage he wrought on the railroad hardly affected either Thomas at Nashville or Union military operations to the south. Ultimately, Hood chose to simply follow Schofield to Nashville on December 1. His shattered army settled sullenly into their exposed and frozen hilltop redoubts, staring across at the storm gathering in the highly fortified Tennessee capital and awaiting their fate.

The initiative now passed from Hood’s Confederates to Thomas’s finally congealing juggernaut. Hood stretched his thinned ranks on a six-mile, east-west line that covered most of the major roads running south from the city but scarcely filled the distance at three men to the yard on fighting front. The general personally set up headquarters at the comfortable John Overton home on the Franklin road and watched developments. So too did the Lincoln administration in Washington. No longer fretful of what havoc Hood might cause in the autumn elections, the Union high command did worry that despite the wreckage of Franklin, the Confederates still posed a threat to undo the successes of the war in the West.

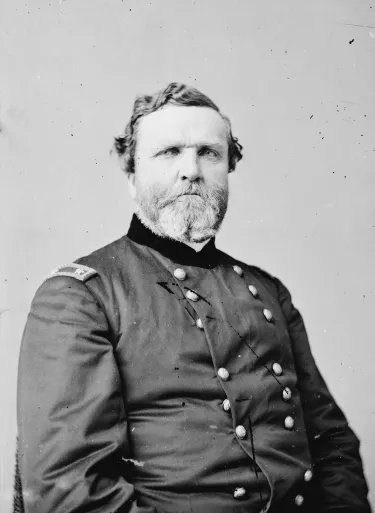

General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant admitted later that he never had been so anxious during the war as at that moment. Tennessee’s military governor Andrew Johnson, soon to join Lincoln’s second-term administration as vice president, also fretted about the danger. But, frankly, the city’s importance to Hood lay less as a political center for reconstructing the state for the Union and more as a major military base that could re-supply his freezing, starving, ill-clad troops from over-stuffed Yankee storehouses. Not unlike Washington, D.C., Nashville by late 1864 had become a boisterous wartime Mecca, occupied by garrison, transient military, partially recalcitrant citizens and purveyors of all manner of vice. Outlying neighborhoods still harbored guerrillas and whatever Tennesseans had decided to remain under Union occupation rather than “refugee” southward. All told, everyone’s gaze rested upon Thomas, the “Rock of Chickamauga,” who, while disturbingly mistrusted by many on both sides as a loyal Virginian, numbered among the most competent fighters in the Union’s pantheon of generals. Still, he was damnably slow, with a proclivity for methodical preparation before hammer-like delivery. “Pap” Thomas, as his troops affectionately called him, intended building a force that would thoroughly complete what Schofield had begun at Franklin. However, Lincoln, Major General Henry Halleck and most of all Grant were too impatient to await such systematic preparation. Some historians suggest that Thomas was not part of Grant’s inner circle, all of whom were veterans of the Mississippi valley war rather than that of the middle South from the Cumberland to the Tennessee, and hence a target for replacement. It helped not a bit that Schofield apparently schemed to replace Thomas or that Grant actually had John Logan (a War Democrat politician in uniform but a fighter, as Grant knew from other campaigns) en route to effect Thomas’s relief. Fortunately, the weather intervened to pull Thomas’s chestnuts (and those of the Union) from the fire.

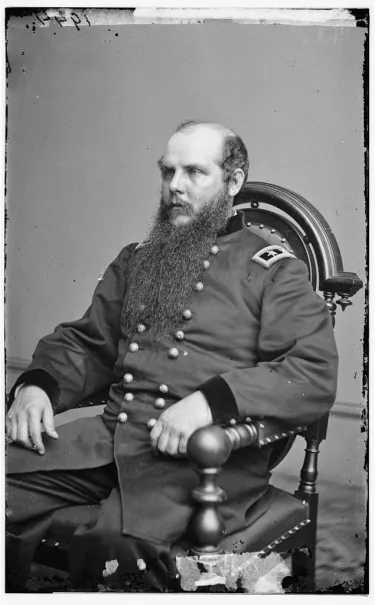

Thomas’s strike force increased. In addition to the men Schofield brought in, another corps under A. J. Smith from the Mississippi valley arrived as well as new recruits from the North and over 5,000 men representing odds and ends of garrisons from all over Tennessee. Thomas counted 71,842 men at the start of the Nashville fighting; Hood numbered 23,053 hunkered down in strong if isolated defensive positions. Several false starts due to an ice storm only increased the tension and drama. Finally, the weather warmed and, despite a dense fog on the morning of December 15, Thomas struck with a superbly planned maneuver. Feinting with his left (which included African-American contingents), the Union commander launched a devastating onslaught of dismounted cavalry and infantry on his right that quickly enveloped the pitiful redoubts constituting the Confederate forward line. Hood’s outclassed army retreated quickly to a more compact second defense line, anchored at Peach Orchard Hill on the right and Shy’s Hill on the left. The fighting resumed on the afternoon of the 16th as Union batteries pounded the new line and repeated dismounted cavalry-infantry assaults finally broke the Rebel position, especially at Shy’s Hill. Hood’s army disintegrated, streaming southward in abject rout. As Schofield recorded years later, “I doubt if any soldiers in the world ever needed more cumulative evidence to convince them that they were beaten.”

Nor would there be respite from the storm. The destroyed army streamed south in horrendous weather, continuously harassed by James Wilson’s Union horsemen and other pursuers. Forrest’s cavalry and Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee’s infantry ably covered the barefoot, ragged survivors at crucial points and the worst part of the ordeal was finally over by the Duck River crossings on December 18. Hood’s remnants finally reached the Tennessee River near Bainbridge, Alabama on Christmas day and three days later completed that passage as a Union naval flotilla sent to interdict the retreat was held at bay by Confederate artillerists. A fortnight later, the 18,742 survivors of Hood’s Tennessee campaign went into camp at Tupelo, Mississippi. The survivors might sing about their leader playing hell in Tennessee, but few could say whether the hell was played on the enemy or themselves. On January 13, the crippled, enfeebled, and demoralized John Hood asked to be relieved of command. What he had taken into Tennessee two months before as a formidable army had now ceased to exist as a credible fighting force. In fact, the once-proud Army of Tennessee was broken up and dispersed to other fronts in North Carolina and at Mobile in last-ditch efforts to halt the ever-advancing forces of the United States and stave off the inevitable. It was not so much that Nashville cost Hood so dearly in killed and wounded (approximately 1,500 to Thomas’s 2,562) but the 4,500 captives (by Thomas’s count) and the disintegration through desertion during the retreat that underscored this battle as decisively delivered the coup de grace to the army, and with it, to its commander and to any lingering hope of defeating the Union and gaining independence, much less establishing a western frontier and wintering on the Ohio.

Contemporaries as well as historians castigated Hood for defeat rather than awarding Thomas honors for the culminating Nashville victory. The redoubtable early military historian Matthew Forney Steele, however, decided, “Of all the attacks made by Union forces in the course of the war none other was as free from faults as this one.” Author of the definitive study of the Army of the Cumberland, himself a veteran of that underrated Union field force, Thomas V. Van Horne suggested, “Seldom has a battle been fought in more exact conformity to plan” than Nashville, referring not only to the great battles of the Civil War, but also in comparison with those of Europe, “fought by the great masters of war.” To this observer, the battle “was distinctive, illustrating generalship which comprehended the minutest of details, as well as the grandest combinations.” Despite the shabby treatment of higher authorities who should have known better, Thomas emerged not only the victor but also the hero of Nashville. It was the completeness of defeat that captured the sorrow of future generations of Southerners rather than the rapture of military perfection for Northerners. Why should Tennesseans and other veterans of the Lost Cause (or their kinsmen) commemorate a disaster or ensure enshrinement of any of this campaign’s disasters, especially Nashville, through preservation of the site of their enemies’ most complete triumph? Accordingly, their tribute to the meaning of Hood’s aborted venture lies in that ominously impressive graveyard behind the McGavock house outside Franklin. Less understandable has been the dearth of enthusiasm by any of their Northern counterparts (including ironically even Tennessee Unionists and their descendants) or the United States government to better mark the sacred ground of Thomas’s most singular contribution to preservation of the Union. Less complete, less pivotal battles, even places less illustrative of the art and science of war have garnered national, state, and even local attention in today’s floodtide of trying to save every inch of Civil War heritage. But, after all, it was Thomas and his masterfully planned, meticulously implemented decisive battle of Nashville, which inspired the stunning recessional words of campaign historian Thomas R. Hay, “The once powerful army of Tennessee was all but a mere memory.” The sun of the Confederacy, frozen in its ascendancy on the icy slopes before Fort Donelson two years before, finally eclipsed dramatically on the snowy hillsides outside Nashville. Perhaps it was not so much Confederate bungling as superior Union battle management that provided those decisive results.

Editor’s Note: ABT would like to clarify a few things in Dr. Cooling’s article. When he mentions that the Battles of Franklin and Nashville have been ignored by preservationists, that is not strictly accurate. As of 2014, ten years after the publication of this article, ABT has saved 195 acres at Spring Hill, 24 acres at Stones River, and 176 acres at Franklin. The problem with large-scale preservation in the Franklin and Nashville areas is that the regions have been heavily developed. This means first that any remaining battlefield land is extremely expensive and second that most battlefields are fragmented and have lost much of their historic integrity.

Partner with us to save five threatened battlefield tracts representing four crucial campaigns in three states.

Related Battles

3,061

6,000