Bloody Horror of Upton’s Charge

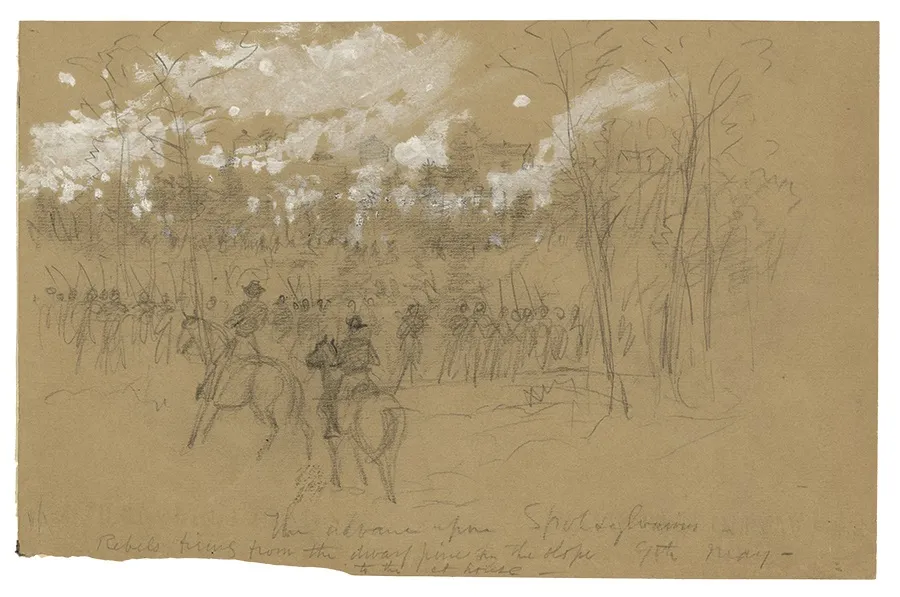

We are lying low, and not a word is spoken above a whisper in our ranks,” recalled a member of the 49th Pennsylvania Infantry. “We see the duty we are expected to perform, and orders are quietly passed along the line in a whisper.” Moments later, nearly 4,500 Union infantrymen sprang to their feet and sprinted across some 200 yards of no-man’s land toward the fortified Confederate position near Spotsylvania Court House. “Quick as lightning a sheet of flame burst from the rebel line, and the leaden hail swept the ground over which the column was advancing, while the canister from the artillery came crashing through our ranks at every step.

In less than two minutes, the Federal tide swept over and into the Confederate works. It was a resounding success, the type of success that the Federal high command had been seeking since it initiated the 1864 spring offensive one week earlier. The Federal assault column gained a foothold inside of the Confederate fortifications, prompting overall Union commander Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to growl, "Pile in the men and hold it."

But within an hour, fierce Confederate counterattacks forced the Yankees back from whence they came. Although the Union assault at Doles’s Salient, a smaller portion of the famed Confederate Mule Shoe Salient, ultimately failed, it bolstered the spirits of Grant. He commented that they had tried with “a brigade today — we’ll try a corps tomorrow.”

The Federal spring offensive had been marred by miscommunication and missed opportunities. In less than one year, President Abraham Lincoln’s principle army, the Army of the Potomac, had entered the Wilderness of Orange and Spotsylvania Counties of Virginia. For the third time, Gen. Robert E. Lee and his vaunted Army of Northern Virginia had bested their perennial foe, stalling the Yankee advance at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5–6, 1864) and thwarting the enemy’s attempt to bring overwhelming numbers down upon the rebel forces. One thing had changed in the last year: Grant was unwilling to give up the fight. Whereas, Maj. Gens. Joseph Hooker and George G. Meade had taken the Army of the Potomac into the Wilderness and given up the initiative to Lee at Chancellorsville and Mine Run, respectively, Grant informed his superiors “I propose to fight it out on this line, if it takes all summer.”

The choking Wilderness hampered the maneuverability of the enormous Army of the Potomac; thus, Grant set his sights on the hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House. The sleepy village that served as the county seat of Spotsylvania County sat at the crossroads of the Brock Road, which ran roughly north to south, and the Fredericksburg Road, which led to the city for which the road was named. By capturing the town, Grant would hold the inside track to Richmond, the Confederate capital, while also shortening his supply line by shifting it from the overtaxed Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Brandy Station to the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad depot at the much closer city of Fredericksburg. Grant further hoped to interpose himself between Lee and Richmond, forcing the old gray fox to attack Grant’s army on terrain that benefitted the Federals. His ultimate goal was not the capitulation of Richmond, but, rather, the destruction of Lee’s army.

By the evening of May 7, Grant’s men were trekking the 12 miles to Spotsylvania. Confederate cavalry, lackluster Federal leadership and luck all played against the Federals. By 8:00 a.m. the next day, Confederate forces had won the race to Spotsylvania.

The Southern Army set up a stout defensive line, with its left anchored on the steep-banked Po River and its right terminating to the northeast of the town. The roughly five-mile defensive line appeared formidable. Confederate soldiers furiously dug into the earth, creating strong fortifications. “It is a rule that, when the Rebels halt, the first day gives them a good rifle-pit; the second, a regular infantry parapet with artillery in position; and the third a parapet with an abatis in front and entrenched batteries behind,” a Union soldier commented. “Sometimes they put this three days’ work into the first 24 hours.”

For as imposing as the Confederate line looked, however there was a major flaw. Its center jutted out from the left and right flank, creating a salient point protruding outward from the main line. This flaw exposed men defending the salient to converging artillery fire, while diluting defensive fire from the salient. All the opposing guns could concentrate on one point, whereas defenders of the salient had to pick out many targets. Even an overshot could still land a killing blow on the far side of the salient. But Lee was convinced by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, his de facto second-in-command, that this point could be held with enough artillery and allowed it to remain.

Meanwhile, Ulysses S. Grant was finding out just how hard it could be to control the Army of the Potomac. The army seemed to live in mortal fear of what Lee was up to. At one point in the Wilderness he commented to a group of officers, “Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time.” He went on to say, “Go back to your command, and try to think [of] what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.”

Grant was also finding flaws in the high command. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, commander of the V Corps, had both a temper and an ego. His VI Corps commander, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, was habitually slow, as was the independent commander of the IX Corps, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside. Cavalry Corps commander Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan couldn’t get along with army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. The only bright spot in the chain of command seemed to be Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, commander of the II Corps, who had the uncanny ability of actually carrying out an order in a timely fashion, unlike his counterparts.

On May 9, Sedgwick was felled by a sharpshooter’s bullet, making the 50-year-old Connecticut native the highest ranking Federal officer to fall in the war. Command of the VI Corps devolved to Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright. Due to the death of Sedgwick and the constant campaigning since May 4, Grant did not mount a major offensive at Spotsylvania that day.

The next day, May 10, Grant tried again to dislodge Lee’s men by applying simultaneous pressure along the Confederate lines. In theory, this should have prevented the Confederates from being able to shift men along interior lines to a threatened point. With much of the Confederate line under pressure, the right hand could not assist the left. Yet this was not the case.

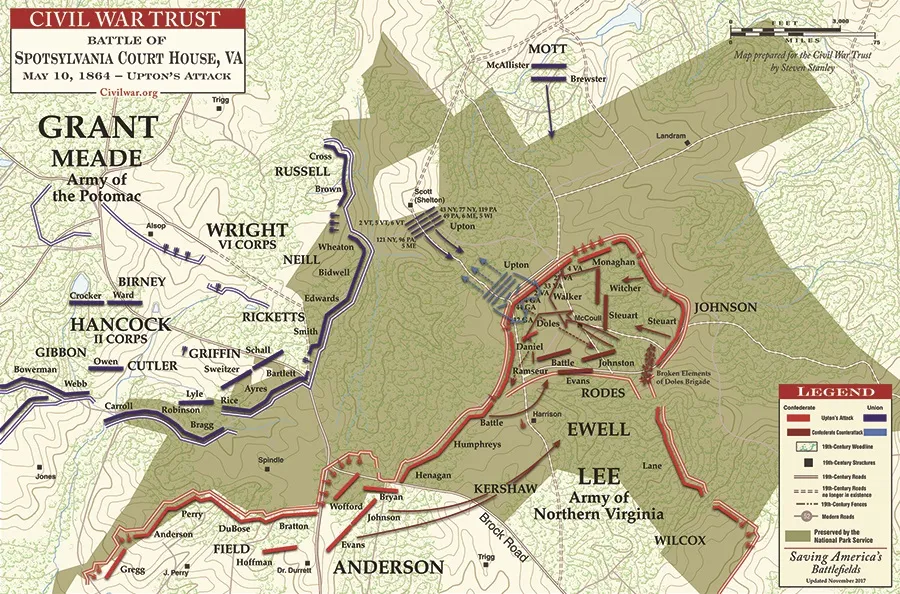

The Federal plan for May 10 called for a portion of the II Corps and the bulk of the V Corps to attack the Confederate left at Laurel Hill beginning at 5:00 p.m. On the Confederate right, Burnside and his IX Corps would attack down the Fredericksburg Road. The most complex and intriguing part of the May 10 attack would strike the Confederate center.

One division of the II Corps, acting as a link between the VI and IX Corps, would strike the tip of the Mule Shoe Salient. This undersized division, led by Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott, was intended to support the main assault column of the VI Corps.

The VI Corps assault column was unique, as was the unit itself. It had been created on May 18, 1862, by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan as a “provisional corps,” yet it remained in service for the rest of the war.

Compared to the other corps in the Army of the Potomac, the VI Corps had seen limited action, primarily at South Mountain, Chancellorsville, Rappahannock Station and the Wilderness. At Chancellorsville, it sustained the highest number of casualties among the seven infantry corps in the army. On numerous occasions, the corps utilized innovative tactics to capture enemy positions. At Second Fredericksburg, soldiers formed “lances,” to take the famed Marye’s Heights. At Rappahannock Station, in November of 1863, their creativity dislodged the enemy from a fortified position. Almost by default, the VI Corps was turning into a specialized task force, and on May 10, it was again called upon for its bravery and innovation.

Union engineer Lt. Ranald S. Mackenzie scouted the Confederate lines on May 10 and found that a portion of the western face of the Mule Shoe was vulnerable to attack. Although the Confederate lines consisted of chest-high fortifications with a protective head log and abatis, the closeness of the line to an adjacent woodlot, some 200 yards away, limited the Confederate field of fire. The woods also concealed any attack force. Nevertheless, the Confederate line was “of a formidable character with abatis in front and surmounted by heavy logs, underneath which were loop holes for musketry.”

Mackenzie reported his findings to Brig. Gen. David Russell. After verifying the report, the VI Corps high command devised a plan of attack. Twelve regiments of infantry were hand selected from brigades in Russell’s division and the division of Maj. Gen. Thomas Neill — some 4,500 men in all. Command of the assault force was given to Col. Emory Upton, a 24-year-old native of Batavia, N.Y. After attending Oberlin College, Upton went on to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated eighth in the class of May 1861.

The young colonel was described as having “a light mustache, high cheek bones, thin face, and a strong square jaw. He had a small mouth and thin, unusually closed lips, which made his mouth look even smaller. His deep blue, deep-set eyes ‘seemed to be searching all the time.’” One biographer described him as being single-minded in his purpose. Upton “never drank, smoked, or cursed, and seldom laughed. He was asocial to the point of being acutely uncomfortable in the presence of civilians.”

Upton was every inch a soldier and unquestionably one of the finest combat leaders to come out of the Army of the Potomac. In late 1862, he had been given command of the 121st New York Infantry, a unit later dubbed “Upton’s Regulars,” due to the discipline he instilled in them.

Accounts vary as to who came up with the overall operational plan for the VI Corps assault on Doles’s Salient, but there is no doubt that it was Upton who executed it. His orders were simple: “You will assault the enemys [sic] entrenchments in four lines.” Corps commander Horatio Wright told Upton, “Capt. Mackenzie will show you the point of attack. Mott’s division will support you.”

Late on the afternoon of May 10, Upton called together his 12 regimental commanders. The knot of officers crept to the edge of the woods, across from Doles’s Salient. Upton laid out his plan of attack. He would use coup de main tactics, incorporating speed and shock to gain the enemy works. He also called for a compact column three regiments across and four regiments deep, a formation reminiscent of the Greek hoplite phalanx or that of the Swiss pikemen.

The first line of the attack consisted of the 121st New York, 96th Pennsylvania and 5th Maine. These regiments would advance with muskets loaded and capped and bayonets fixed. When the first line broke through, the New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians were then to wheel to the right and dislodge the Confederates in the western salient and silence the rebel battery, while the 5th Maine was to wheel left and clear the eastern salient. The second and third waves, which consisted of the 5th Wisconsin, 6th Maine, 49th Pennsylvania, 119th Pennsylvania, 77th New York and 43rd New York, would pile into and onto the earthworks. They would keep the line of retreat open while also supporting the forward movements of the first line. The fourth line — which consisted of the 6th, 5th and 2nd Vermont — would hold fast at the edge of the wood line as a reserve. The second, third and fourth lines were to load their muskets and fix bayonets, but they were not to place the percussion cap on the cone of the gun. Upton wanted to thwart any intentions of his men of stopping to shoot at the enemy, thus costing the attack force momentum. “All of the officers were instructed to repeat the command ‘forward’ constantly, from the commencement of the charge till the works were carried. No man was to stop and succor or assist a wounded comrade.”

A pre-assault artillery barrage utilizing three VI Corps batteries — 18 guns in all — was planned to soften the enemy position. If all went well, Upton’s men would bore through the Confederate lines, creating a gap for the rest of the Union army to exploit. Mott’s men, in theory, would support Upton’s men and help expand the gap. The problem was that Upton and Mott did not coordinate closely with one another, and Mott’s role in the assault seemed to be a mystery.

Across the no-man’s land, the Confederates were aware something was amiss. Their pickets had been driven in by companies of the 65th New York and 49th Pennsylvania, and there seemed to be an unusual amount of activity.

Doles’s Salient was named for George Doles, a Georgia lawyer turned brigade commander. His three Georgia regiments manned the works. One Georgian thought that “a death-like stillness {hung} over the lines.” Around 3:30 p.m., the Federal assault along Lee’s lines started with a fizzle. Warren led his troops in at Laurel Hill an hour and a half too soon. Burnside’s IX Corps launched an impotent attack on the Confederate right later in the day. At 5:00 p.m., 1,500 men from Gershom Mott’s II Corps division dutifully went forward. Unfortunately, to their right, Upton did not budge. His men were ordered not to go in yet. Upton waited for nearly another hour and a half before he gave the green light to his attack column.

Sometime between 6:15 and 6:35 p.m., Upton’s men burst from the tree line. One Southerner exclaimed, “Make ready boys — they are charging!”

A Vermont private described the scene:

At the signal, Col. Upton with his three lines of infantry jumped to their feet, and rushed ahead across the open field, to the enemy’s works, while we cheered as lustily as we could to heighten the effect, and help create a panic among the enemy. How terribly the bullets swept that plain, and rattled like hailstones among the trees over our heads. The boys could not be restrained in their wild excitement, and without waiting for orders … they rushed in after the other brigade, and we drove the enemy from his first line of works.

One member of the 96th Pennsylvania lamented, “Many a poor fellow fell pierced with rebel bullets before we reached the rifle pits.… When those of us that were left reached the rifle pits we let them have it.”

The battle at the Confederate line turned into “a deadly hand-to-hand conflict.” Upton saw “the enemy sitting in their pits with pieces upright, loaded and with bayonets fixed, ready to impale the first who should leap over, [they] absolutely refused to yield the ground.”

It was a scene of utter horror and pandemonium, with the bayonet used freely. Men thrust and threw bayonet-tipped muskets at one another “pinning them to the ground.” Shocked Confederates threw down their rifles and surrendered. Scores of them were pointed toward the tree line and told to make their way toward the Union lines. As they did so, a member of the 49th Pennsylvania described how “a rebel lieutenant, after passing to the rear, orders his men to pick up the guns that our dead and wounded have left on the field and fire on us from the rear.” To stop this from happening, “Sergeant Sam Steiner” put a “ball into the rebel’s back, who threw his hands up and dropped to the ground. This stopped the picking up of guns.” One Confederate said that “Gen. Doles was captured, but when the enemy was driven back he fell in … & resumed command.”

Upton’s coup de main tactics worked to perfection. His men covered the 200 yards of open land within two minutes. Scores of Confederates surrendered. Some leapt out of the front of their works into the no-man’s land and retreated along the front of their works, before re-crossing and joining their comrades.

One Confederate thought that “The Yankees fought with unusual desperation, and where the artillery was, contended as stubbornly for it as though it was their own.”

The artillery he was referring to were the guns of the Richmond Howitzers, four pieces of which sat in the western side of the salient. A member of the Howitzers stated that “we poured a few rounds of canister into their ranks, when we are ordered to ‘Cease Firing — our men are charging!’” It was not a Confederate counterattack. It was a large number of Doles’s brigade, who “had no muskets” and were prisoners of war. The Howitzers redoubled their efforts, angered that their comrades “had surrendered without firing a shot and were going to the rear as fast as their cowardly legs would carry them.” In the end, “no artillerists could stem the torrent now nor wipe away the foul stain upon the fair banner of Confederate valor.”

On the east side of the breakthrough, the famed Stonewall Brigade fought desperately to stop the Union wave; on the western side, it was Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel’s brigade of North Carolinians. Reinforcements were needed when Lee arrived on the scene. For the second time in four days, he watched as a portion of his army fell apart around him. Richard Ewell arrived too, bellowing, “Don’t run boys, I will have enough men here in five minutes to eat up every damned one of them!”

For all of the weaknesses that the salient presented, one advantage was its interior lines, which allowed faster movement inside of the position. Southern forces began arriving en masse within 30 minutes of the initial breakthrough. Federal reinforcements did not materialize.

Upton was becoming hard-pressed. He looked back for his fourth wave, which should have been positioned the edge of the tree line as reinforcements, but they weren’t there. The Vermont boys, like Upton, had their fighting blood up and had charged across the field and into the fray without orders. Ammunition was running low and, for whatever reason, no one in the Union chain of command had thought to have a mobile reserve of troops ready to support Upton. Reluctantly, the New Yorker called for his men to withdraw. “We don’t want to go. Send us ammunition and rations, and we can stay here for six months,” decried Upton’s dejected soldiers.

Had they stayed, they would have become Confederate prisoners, so Upton and his men gave up the field. His hour or so of fighting had breached the Confederate lines and secured some 913 enlisted men and 37 Confederate officers as prisoners. Emory Upton was visibly upset after the attack that his men had been driven back. His column lost some 1,000 men in the assault, with 216 of them from the 49th Pennsylvania, an exceedingly high number given the fact that only six companies from the regiment were engaged.

The Federal high command had not only failed to properly support or reinforce the assault, they had also failed to properly coordinate it — something that was now a recurring theme in the week-old campaign. Although a failure, the attack on Doles’s Salient showed Grant that Lee’s line could be broken and that the Confederate salient was a weakness.

Following the Union withdrawal from the salient,

a Confederate band moved up to an elevated position on the line and played "Nearer My God to Thee." The sound of this beautiful piece of music had scarcely died away when a Yankee band over the line gave us the "Dead March." This was followed by the Confederate band playing the "Bonnie Blue Flag." As the last notes were wafted out on the crisp night air a grand old style rebel yell went up. The Yankee band then played "The Star-Spangled Banner," when it seemed by the response yell, that every man in the Army of the Potomac was awake and listening to the music. The Confederate Band then rendered "Home, Sweet Home," when a united yell went up in concert from the men on both sides.

In less than 48 hours, the two sides would again fight in the Mule Shoe, but this time on a far larger and bloodier scale.

More from this issue of Hallowed Ground: Certain Death | Spotsylvania Court House: Hell Defined