Certain Death

It was a “panoply of horror.” A “pandemonium of terror.” A “literal saturnalia of blood.” One Federal soldier described the scene as “a Golgotha” — a place of skulls.

Union and Confederate soldiers had endured years of privations and pitched battles, yet nothing had prepared them for the fighting in the Mule Shoe Salient at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12, 1864. “I have, as you know, been in a good many hard fights, but I never saw anything like the contest,” wrote one Louisiana soldier.

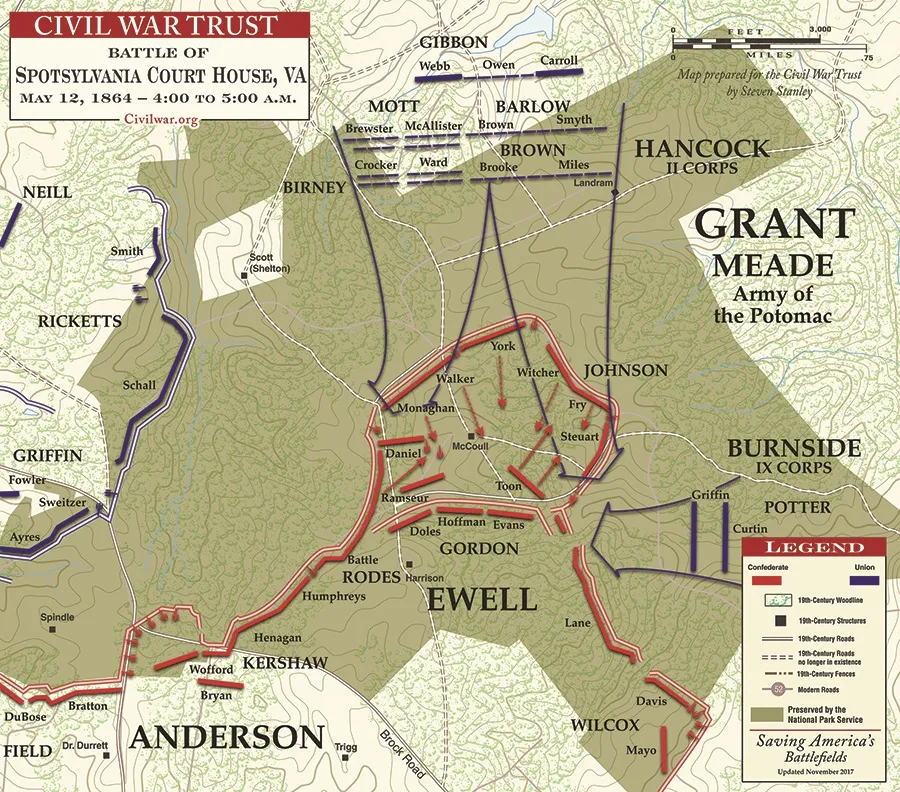

At 4:35 a.m., some 20,000 Federal soldiers launched a furious attack on the center of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s defenses. They shattered the Confederate line and captured more than 3,000 prisoners, along with 22 cannons, two general officers and 30 stands of colors. “Men in crowds with bleeding limbs, and pale, pain-stricken faces, were hurrying to the rear,” a Virginia artillerist said.

On the Confederate right, the Federal IX Corps attacked in force to provide additional pressure. In the center, Federal soldiers flooded into the breech in the Confederate line.

As the Army of Northern Virginia teetered on the brink of destruction, Lee rode toward his embattled center. “Not a word did he say,” noted one observer, “but simply took off his hat, and as he sat on his charger I never saw a man look so noble, or a spectacle so impressive.”

Lee watched as his army crumbled around him.

The collapse of the Mule Shoe Salient was of Lee’s own making. The Confederate line at Spotsylvania ran for nearly five miles, laid out as troops rushed on to the field — often at a moment of crisis — to resist Federal assaults. “Run for our rail piles; the Federal infantry will reach them first, if you don’t run!” implored Confederate cavalrymen as foot soldiers arrived on the scene. In response, one Southern soldier said, “Our men sprang forward as if by magic,” while another described them “rushing pell-mell at full speed around there just as the enemy came up.”

Lee’s army unwound along ridgelines that gave his men strong defensible positions and effective fields of fire. And as soon as they staked out a position, they began to fortify it. “The rebel works were constructed as follows,” a New Yorker later explained:

A layer of stout logs close together & breast high was made and banked on the front side with earth. Above this with space to fire between was laced another log larger than the others protecting the heads of the defenders. For several rods in front the trees had been felled to fall outward and form by their entangled branches a dense abattis. Sometimes these branches of these trees had been sharpened so as to impale assailants…. Behind such works Lee’s veteran army lay and was virtually unassailable.

The left flank of the Confederate line was the strongest, anchored on the Po River and along the low crest at the southern edge of a field on the Sarah Spindle Farm — an area also known as Laurel Hill. The right flank of the line terminated southeast of the village of Spotsylvania Court House itself. While it lacked the topographical advantages of the left flank, the Confederate right was relatively secure, given that the bulk of the Federal army was massed along the Confederate left and left center.

The weakest point on the rebel line was its center. In following the natural contours of the land, the chief topographical engineer of Lee’s army, 44-year-old Maj. Gen. Martin Luther Smith, had laid out a giant bubble known as a salient. Such protrusions are an inherent weakness; a breakthrough at any point along the line lets the enemy suddenly command a position behind the entire salient and makes the entire position untenable. The concentrated firepower of converging artillery and small-arms also make a salient vulnerable, which Confederate infantrymen nestled in the tip of the salient recognized almost immediately. “After throwing up breastworks, we found that the Yanks had a cross fire on our regiment,” one of them wrote in a letter published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “We then went to work and built pens, each holding eight or ten men.” Also called traverses, these pens were breastworks built inside the line, perpendicular to the main works, that offered soldiers a degree of additional cover.

The protrusion, a mile across at its base, curved in a large arc that conferred a name on the position through undeniable resemblance: the Mule Shoe Salient.

Lee, a former engineer himself, became aware of the salient during an inspection of the line on May 9. However, rather than correct the flaw by repositioning his line, he deferred to the judgment of his de facto second-in-command, Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, who oversaw the center of the overall Confederate position. The 47-year-old Second Corps commander was convinced he could hold the salient if supported by enough artillery. Smith was convinced, too. Even the artillerists themselves agreed: “The breastworks were built, we would be in place and, supported by infantry, absolutely impregnable against successful assault,” one of them said.

Even after a near disaster along the line on May 10, when Col. Emory Upton attacked a protruding spot known as Dole’s Salient, Lee let the Mule Shoe position stand.

Federal commander Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant recognized that the May 10 attack had ultimately failed because his forces had been unprepared to take advantage of Upton’s surprising success. He decided to try again, and on May 11, began shifting Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps to concentrate opposite the very tip of the Mule Shoe in preparation for a dawn attack.

Rain fell in torrents as the men marched, turning roads into quagmires and streams into raging rivers. Guides became lost as the Federals slogged into position. “The wind sobbed drearily over the meadows and through the trees, rain fell steadily, and the night was so dark men had to almost feel their way,” wrote one Mainer.

“The movement was necessarily slow with frequent halts,” another soldier recalled, “at which time the men, worn out by loss of sleep and the terrible nervous and physical strain they had endured during the past eight days, would drop down for a moment’s rest, and be asleep almost as soon as they touched the ground.”

Lee was acutely aware of the Federal movement, but he failed to understand its intent. He believed that, after a few days of stalemate, Grant had decided to give up the offensive and shift from his axis of advance — the Brock Road — over to the Fredericksburg Road, along which he would retreat. Yearning for the opportunity to take the offensive himself, Lee began preparations to pursue the fleeing Federals. To expedite this, he called on Ewell to “withdraw the artillery from the salient . . . to have it available for a countermove to the right.” Moving these guns across muddy farm roads, Lee believed, would hamper their ability to link up with the rest of the Confederate army in a timely fashion. With a single stroke of his pen, Lee removed the 22 of the 30 cannons — whose presence was a prerequisite for holding the salient — from the Confederate center — the very point Grant was preparing to attack.

Compounding the problem, neither Lee nor Ewell bothered to tell the commander on the field — Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson — that his division was losing its artillery support. Only when the complaints of subordinates reached his headquarters did Johnson become aware of the dire situation Lee had placed his division in. Unconvinced that the Federals were retreating, Johnson seethed over the loss of his artillery and the slight against his chain of command. He went to Ewell in person to protest and to inform his superior that something was amiss to his front. Ewell relented and allowed the artillery to return, but it would take several hours before the guns could be rolled back into position.

In the meantime, Johnson ordered his brigades “to be on the alert, some brigades to be awake all night, and all to be up and in the trenches an hour or so before daylight.” He expected trouble. And trouble was, indeed, coming.

The night’s rain had cooled the muggy May heat, and fog drifted up out of the bottomlands, forcing Hancock to delay his assault until visibility improved. When he finally sent the men forward, Hancock — worried about the desperate fight he knew lay ahead — lamented, “I know they will not come back! They will not come back!”

“Nobody knew exactly the position of the works or the nature of the ground, and so we had to take our chances, moving forward till we struck them,” a Federal staff officer said. It took only minutes to reach the Confederate skirmish line, which, situated in a sunken farm lane resembling a deep trench, was mistaken for the main line. The Yankees gave out a “Huzzah!” as they stormed in. They quickly realized their mistake. Gazing through the gloom, “[W]e saw very plainly where we were at and we needed no orders, for the longer we were getting to them, the more ready they would be,” said Stephen P. Chase of the 86th New York. Swiftly, the Federals swarmed out of the skirmish line and across the field toward the tip of the Mule Shoe.

“[T]hey came in seventeen lines, one line just behind the other, and we counted them,” wrote Thomas Reed of the 9th Louisiana, “and some fellow said: ‘Look out! boys! We will have blood for supper.’”

Johnson had anticipated a dawn attack, and officers had ordered the men to load their weapons and then stack their arms the night before. Normally, this would have been a wise move, but Mother Nature intervened, dumping an inordinate amount of rain from the heavens.

Rising in unison, the Confederate line took aim. Maj. Gen. James Walker noted how his Stonewall Brigade “leveled their trusty muskets deliberately . . . with a practiced aim which would have carried havoc” into the ranks of the advancing Federals. But when the command to fire came, “pop, pop, pop” rang out along the line, not “bang, bang, bang.” Almost to a man, the guns failed to discharge because of wet powder.

The 26th Michigan and the 140th Pennsylvania came over the top, followed by scores of other Federal regiments. The attack became a free-for-all. Half-dressed Confederates tried to stand their ground as Yankees “poured in one irresistible mass upon them.” The Mule Shoe became a “boiling, bubbling and hissing caldron of death.”

The rebel artillery rolled back into the salient just as the Federal wave crested the works. “Most of this battalion reached the salient point just in time to be captured,” recalled artillerist Thomas Carter. Only one of Carter’s four guns managed to unlimber and get into position, firing off a single round of canister, before it was overrun. “Don’t shoot my men,” Carter pleaded. While the Federals took Carter and his men prisoner, they could not haul away the guns; Confederate infantrymen shot the horses to thwart them.

The Federal wave opened a gap in the Confederate line at least a half-mile wide and a half-mile deep. Johnson fell prisoner, as did Brig. Gen. George “Maryland” Steuart and thousands of other butternut soldiers.

Despite the immediate and stunning Federal success, the attack force began to lose its cohesion, and reinforcements did not materialize to exploit the gap. The same weakness that had undercut the success of the May 10 attack seemed doomed to repeat.

Robert E. Lee — the man ultimately responsible for the initial flaw in the line and the man who’d weakened it further by withdrawing the artillery, and also the man who had woefully misread Federal intentions — arrived on the field with a monumental task before him. Somehow, he had to stem the flood of Federals into his center, rectify the weakness of his line and show leadership amidst chaos. He became the calm eye at the center of the hurricane.

The Mule Shoe, Lee now admitted, if somewhat belatedly, was untenable. He ordered his engineers to seal it off by laying out a new line one mile south of the tip of the salient. The survivors of Johnson’s division, already streaming to the rear, were rallied and set to work on construction.

Lee needed to buy time for the work to progress, and he bought that time with lives.

Near the western base of the salient, the stout North Carolina brigade of Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel stemmed the Federal tide, although Daniel himself was mortally wounded in the effort. A few pieces of artillery wheeled around to provide backup. “[T]his combined fire of infantry and artillery was more than human flesh could stand and it was impossible for them to reach our lines,” said Maj. Cyrus B. Watson of the 45th North Carolina.

On the eastern side of the salient, the Federals had cleared most of the Confederate resistance, although the North Carolina brigade of James Lane still held.

Between those two extremes, Lee had a reserve division commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon, which was already trying to provide a rallying point for some of the retreating Confederates. “[T]hey were very hard to rally,” admitted an artillerist who had retreated with the infantrymen. “[M]any of them were still running and looked as if they had no idea of stopping at all.”

Lee prepared to lead Gordon’s men in a counterattack. “The General’s countenance showed that he had despaired and was ready to die rather than see the defeat of his army,” a Confederate soldier said. Gordon and his men, however, convinced their commander to turn back: His life was far too valuable.

Rather than attack the center of the Federal mass, Lee and Gordon dispatched units to the edges of the bulge. Working their way inward, brigades of Georgians, Virginians, North Carolinians, Mississippians, Alabamians and South Carolinians traded their lives for time. Foot by foot and yard by yard, the Confederates wrestled back their abandoned works. “[T]he enemy came forward in immense numbers and made the most desperate attempt to recover their lost ground,” wrote Lt. Josiah Favill, a staff officer in the II Corps. “They seemed determined to gain back at any cost what had been lost, and the most severe close fighting of the war ensued.”

Butternut soldiers managed to recapture all but 400 yards of their original line, but it came at a high cost: In addition to Daniel, brigade commanders Stephen Ramseur, Abner Perrin, Samuel McGowan, Robert Johnston and Thomas Garrett all fell either killed or wounded. Thousands more Confederate infantrymen fell dead or wounded “[l]ike the debris in the track of a storm.”

Along the salient’s western face, where the line turned toward the south, both sides poured men into action. Federal reinforcements finally swept into the fray, using the protective confines of a swale that funneled men toward the very spot Confederate forces were also converging. “I have heard that blood-drenched bullet swept angle, called ‘Hell’s Half-acre,’” Robert Robertson added. Many called it “the slaughter-pen of Spotsylvania.” Most remembered it as the Bloody Angle — “a seething, bubbling, roaring hell of hate and murder,” said John Haley of the 17th Maine.

By 9:30 a.m., the area around the west angle encompassed perhaps 150 yards of the works, but those few yards witnessed some of the most hellacious hand-to-hand combat of the American Civil War. “The fighting was horrible,” one Mississippian said. “The breastworks were slippery with blood and rain, dead bodies lying underneath half trampled out of sight.”

The 16th Mississippi’s flag bearer, Sgt. Alexander Mixon, was shot while leading his regiment into the dark heart of the fray. Only wounded, he picked up his flag, staggered forward, but was then shot through the head. The flag remained standing at the very apex of the west angle. Union soldiers charged forward to capture the colors, but Mississippi and Alabama men counterattacked with equal ferocity.

“At every assault and every repulse new bodies fell on the heaps of the slain, and over the filled ditches the living fought on the corpses of the fallen,” said a New Jersey officer. “The wounded were covered by the killed, and expired under piles of their comrades’ bodies.”

With Federals on one side of the blood- and rain-soaked trench, and Confederates on the other side, the fighting took on an intimate nature. Men reached over the works and blasted their foes at point-blank range. Bayonet-tipped muskets thrust through and over the works into soft flesh. A Federal, after seeing one of his officers gunned down from atop the works, hurled his musket like a spear at the Confederate who had fired the shot. “The force with which he threw it,” said a witness, “drove the bayonet entirely through his chest, burying at least four inches of the muzzle of the gun in the breast of the Confederate, who uttered the most unearthly yell I ever heard from human lips, as he fell over backward with the gun sticking in him.”

Wounded men fell into trenches that were filled with at least a foot of bloody, muddy water. Some, unable to lift themselves back up, drowned as other wounded and dead men fell upon them. Corpses were stacked like cordwood and used as makeshift works. One dead Union soldier absorbed an estimated “five thousand” minie balls — enough to turn his body to “sponge.”

As Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan’s brigade charged toward the West Angle, bullets shattered the staff of the 1st South Carolina’s flag. As the assault began to falter, color bearer Charlie

Whilden snatched up the fallen banner and wrapped himself in it, pushing forward through the knee-deep mud with his regiment and the rest of the brigade in tow. Wilden planted his Palmetto flag, and his comrades rallied around it.

For every wave Grant sent in, Lee countered by shifting more men into the fight from other parts of the Confederate line. Grant’s failure to put significant pressure on the entire Confederate line gave Lee the flexibility to shift troops to his embattled center. Federals kept arriving at the front, but officers had no place to pack them in. The resulting bottleneck left Federals sprawled from the outer edge of the works in a blue carpet that led all the way back across the assault field.

In an attempt to break the impasse, Union II Corps commander Hancock rolled some 30 guns into line along the Landrum farm lane — roughly 400 yards from the Bloody Angle — and started pounding friend and foe alike. He then ordered up other ordnance, 24-pound Coehorn mortars, intended to lob shells into and over the works. Unfortunately, the green cannon crew was firing the guns for the first time in anger. Many of their shells fell short, hitting their own men lying in front of the Angle. Hancock’s idea was a failure.

Then Lt. Richard Metcalf ran two cannon up close to the Bloody Angle and began belching canister at nearly point-blank range. Mississippians flooded out of the works in an attempt to take the guns, but loads of double canister quickly dissuaded them. Still, Metcalf’s section suffered a fearful toll in its advanced position. He lost all of his horses, and all but two of his men were killed or wounded. The guns, mired in mud, had to be abandoned. One had discharged nine rounds, the other 14.

Small-arms fire flew around the Angle so intensely that a 22-inch oak was “hacked through by the awful avalanche of bullets packing against it.” The oak, located in the fourth traverse from the Angle, toppled onto members of the 1st South Carolina, injuring several of them. Musketry fire also mowed down an 18-inch red oak and an eight-inch hickory in the same traverse. In all, some three acres of woods were nearly destroyed. “The north side of the trees which stood in the rear of our works there was not a vestige of bark left,” said Thomas T. Roche of the 16th Mississippi. “Every small branch had been cut away and the large limbs were hanging frayed, frazzled and twisted.” It looked like an army of locusts had swarmed through, said another eyewitness. After the war, as a testament to the ferocity of the fighting, soldiers returned to the battlefield and retrieved the stump of the 22-inch oak. It eventually made its way to the Smithsonian Institution, where it remains today.

For the next 17 hours, the two sides settled into a routine of firing, then shifting units from the front line to the rear and back. Grant’s men could not regain the momentum that had carried them so far earlier in the day. For Lee, the stalemate meant that his men could construct their new defensive line unmolested.

By 2:00 a.m. on May 13, Confederate troops were finally ordered to slip away from the front line, their Herculean task accomplished. The new line was ready.

By the time dawn lightened the drizzling sky, Federals were mounting a cautious pursuit. They crept forward through what was left of the tree line to their front and emerged into the open fields of Neil McCoull’s and Edgar Harrison’s farms. Ahead, they saw a frowning line of freshly churned dirt, abatis 100 yards deep and fortified batteries. Lee had not abandoned the field. All of the fighting they had done the day before was for naught.

In all, the fight for the Mule Shoe cost some 17,000 victims, most of whom carpeted the area around and within the salient. Lee lost about 8,000 men killed, wounded or missing, including 3,000 captured from Allegheny Johnson’s division alone. Grant lost as many as 9,000. “The one exclamation of every man who looks on the spectacle,” said one soldier, “is, ‘God forbid that I should ever gaze on such a sight again.’”

And the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House was yet far from over.

More from this issue of Hallowed Ground: Bloody Horror of Upton's Charge | Spotsylvania Court House: Hell Defined