Book: The Battle of New Market Heights

The Civil War Trust recently had the chance to interview Jimmy Price, the author of The Battle of New Market Heights: Freedom Will Be Theirs By The Sword, a new account of this important 1864 battle where USCT troops met some of the Army of Northern Virginia's most veteran units.

Civil War Trust: Your new book, The Battle of New Market Heights, is a welcome addition for those who want to learn more about this important 1864 battle. What motivated you to write an account of this battle?

Jimmy Price: I first encountered the story of the battle ten years ago when I was an intern with Richmond National Battlefield Park. Eight years later I was working at the Dabbs House in Henrico County and one of the main tasks I was given was to interpret the fighting that took place there in 1862 and 1864. That was the first time that I conducted an in-depth study of the battle, and I began to ask myself why a battle in which fourteen African Americans had received the Medal of Honor was not being talked about. In order to force myself to learn as much about the battle and the United States Colored Troops as a possible, I began writing a blog entitled The Sable Arm which “took off” much quicker than I had anticipated. It was through the blog that I was approached by The History Press to write the Sesquicentennial history of the battle. It is my hope that the book will serve as the starting point for anyone wishing to conduct research on this fascinating topic.

Help set the stage for this battle. What were the Union and Confederate forces doing at this time?

JP: By this stage of the war, the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign was four months old and Robert E. Lee’s Confederate lines were being stretched by Ulysses S. Grant’s continuous offensives like a rubber band about to snap. Sheridan was chasing Early through the Shenandoah Valley, and Lee constantly had to decide how many men he could send to Early’s corps without making his Petersburg defenses too weak. When Grant caught wind that Lee had dispatched an entire division to the Valley in late September, he decided that it was time to attack the entrenchments around Petersburg and Richmond once again. The resulting series of battles is what historians refer to as the Fifth Offensive.

As was the case in his third and fourth offensives, Grant decided to launch an assault north of the James River from the Federal bridgehead at Deep Bottom, in addition to his main effort against Petersburg. This would ensure that Lee could not shift reinforcements from one side of the river to the other and, if the gods of war decided to grant him a miracle, Richmond might just fall into Union hands. Grant chose Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James to be his strike force and Butler came up with a plan that called for his army to cross over on the morning of September 29, 1864 and launch a two-pronged assault against Richmond’s defenses. One of those prongs would consist of United States Colored Troops, who Butler hand-picked because, according to his own words, he wanted “to convince myself whether the negro troops will fight, and whether I can take, with the negroes, a redoubt that turned Hancock's corps on a former occasion.” The redoubt that Butler was referring to was New Market Heights.

You offer a kinder portrayal of Benjamin “Beast” Butler than is found in most Civil War literature. How does Butler fit into the larger story of New Market Heights?

JP: Yes, well it’s hard to get a good read on Butler, even nowadays when Civil War biographies abound. He has come down as a one-dimensional caricature, presented as the money-grubbing, goofy-looking political general who was known only for his infamous “woman order” during his occupation of New Orleans, his comical nicknames of “Beast” and “Spoons,” and the fact that he got “bottled up” at Bermuda Hundred before eventually being given his just desserts after the first attempt to take Fort Fisher in early 1865. And while there are certainly elements of truth in such a portrayal of Butler, there is a much more complex man underneath this façade that Civil War historians rarely care to explore. While Butler was a political general in every sense of the term, he was able to transform from a prewar Democrat who voted for Jefferson Davis as the Democratic nominee during the presidential convention of 1860 to a Radical Republican leading the army with the largest contingent of black troops in any Union army. While one could argue that he was merely conforming himself to the political outcomes of the war, there is no question that Butler came to respect and care deeply about the African American soldiers under his command. Furthermore, the plan of attack that he came up with for the assault on Richmond showed that he was no slouch when it came to military matters. Thus, when it came time to storm New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, it was Butler who decided to make his United States Colored Troops the tip of the spear and who personally rode up to them as they were about to step off and ordered that their battle cry should be “Remember Fort Pillow!” And when one reads the letter that he wrote to his wife after riding across the corpse-strewn battlefield, one reads a somber Butler stating that “I have not been so much moved during this war as I was by that sight.”

How did facing USCT troops impact the typical Southern soldier at New Market Heights? ...And did their opinion of African-American troops change after the battle?

JP: Well, it goes without saying that the Southern soldier did not harbor any particular fondness for black soldiers in his heart. The Confederacy viewed the use of United States Colored Troops as “inciting servile insurrection,” which was a nightmare come true for anyone who could remember back to what Nat Turner and John Brown had done. Thus, the Confederate Secretary of War made it clear that “slaves in flagrant rebellion[meaning USCTs] are subject to death” and that they “cannot be recognized in any way as soldiers subject to the rules of war…summary execution must therefore be inflicted on those taken [prisoner].” While this policy was put in place only sporadically, atrocities committed at places like Milliken’s Bend, Fort Pillow, and The Crater show it was implemented on more than one occasion. And it wasn’t just Southern soldiers who despised USCTs. After the Crater, one Virginia woman wrote to her husband who was a soldier in Lee’s army that he must, “shoot [black soldiers], dear husband, every chance you get…It is God’s will and wish for you to destroy them. Your [sic] are his instrument and it is your Christian duty.” So the black soldiers and white officers who attacked New Market Heights suffered form no delusions as to what might happen to them should they fall into enemy hands.

In the aftermath of the battle some Confederate soldiers were moved to sympathy after witnessing such a brave charge into the face of certain death. One wrote that “in my opinion, no troops to that time had fought us with more bravery than did those negroes.” A soldier in the same brigade, however, bitterly recorded in his diary that “our men now have a perfect contempt for negro soldiers. It is almost a pity to put such things into battle.”

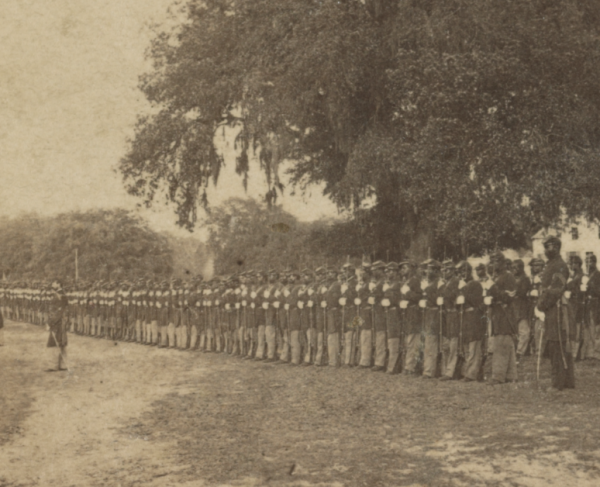

Tell us more about the USCT regiments that participated in the attack on New Market Heights? How experienced were these units?

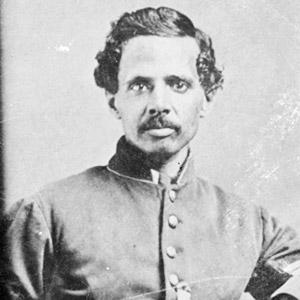

JP: The men who made up Butler’s USCT units came from all over, and while many were former slaves, many were also free men who had enlisted to fight for equality as well as freedom. For instance, Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood of the 4th USCT was a freeborn college graduate who had traveled to Liberia and was active in the American Colonization Society before the war. Former slave Richard Etheridge of the 36th USCT would go on to win the Coast Guard’s Gold Life-Saving Medal for the heroic rescue of an entire ship’s crew off the Outer Banks in 1896. Powhatan Beaty of the 5th USCT was born a slave near Richmond, but gained his freedom, won the Medal of Honor at New Market Heights, and then went on to have a successful career as a Shakespearean actor. So it was a pretty diverse group of men who went into action that day.

As far as experience is concerned, for the most part, the black regiments who assaulted New Market Heights had not seen heavy fighting. Many of them had seen sporadic fighting when the Union army made its initial attempt to seize the city of Petersburg, and many had been held in reserve during the Battle of the Crater – just close enough to watch their comrades get slaughtered and take a few random casualties from the storm of lead that was flying through the air at the time. New Market Heights would be their first – and in many cases, last – taste of full scale combat.

The Confederate’s New Market Line sounded like a formidable defensive challenge. What sort of obstacles did the USCT forces face when attacking these entrenchments?

JP: Yes, the New Market Line was not a happy place to be on the morning of September 29, 1864. The Confederates had begun work on it in 1862 to protect the New Market Road, which ran straight into Richmond. It had defied two previous attempts to take it during the First and Second Battles of Deep Bottom, not so much because of its depth, but because the Confederates took advantage of the terrain to create a lethal killing ground. The heights were protected by artillery which could sweep the entire field and the rifle pits were manned mostly by veteran troops, including the famous Texas Brigade formerly commanded by John Bell Hood. To make matters worse for the attacking USCTs, the Rebels had strewn the approach to the works with obstacles that would not only block their approach, but also slow them down so that their ranks would be decimated from musket and artillery fire. These obstacles were the precursors to the barbed wire that would wreak such havoc on the battlefields of the First World War. The first obstacle encountered was called slashing, and it was described by one eyewitness as a process by which “the trees are felled outwards, at right angles to the work, narrow belts only being left in the hollows of a stream to cover the retreat of pickets or skirmishers.” If the USCTs made it through the slashing they would then face a second series of obstacles known as chevaux-de-frise, which were structures made by sharpening the ends of trees and connecting them together through large logs. If anyone made it through these two lines of obstacles, they would then have to climb up the parapet and deal with the Confederates behind the wall. Not an easy task by any stretch of the imagination.

There were a grand total of 16 Medals of Honor awarded for this one action – 14 of which went to African American soldiers – yet very little has been written about this battle until now. Why has New Market Heights received such short shrift?

JP: I think there are several reasons.

First, there was very little scholarship done on the battle until Dr. Richard J. Sommers published Richmond Redeemed in 1981. There is a lingering air of confusion over what exactly took place during the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign simply because it lasted so long, covered so much ground, and was extremely complex. It wasn’t an Antietam or a Gettysburg, where the armies fought for a few days and there was a clear cut winner and loser. While the campaign itself has received more coverage in the past ten years or so, there is still very little written on the fighting that took place on the north side of the James River. Until someone is willing to tackle the battles that took place at Deep Bottom, Darbytown Road, and Second Fair Oaks, that air of confusion will remain in place.

The second reason has to do with the fact that African American troops were involved. While black veterans of the Civil War received recognition after the war and were celebrated within their own communities, public knowledge of their participation bottomed out in the first half of the twentieth century. Dudley Taylor Cornish’s The Sable Arm, published in 1956, and the release of the film Glory in 1989 were two key factors in the rejuvenation of America’s interest in black participation in the Civil War.

It is through the work of historians like Cornish and Sommers, as well as the efforts of entities like the National Park Service and Civil War Trust that the story of the United States Colored Troops is no longer languishing in obscurity. And with the advent of the Sesquicentennial and the publication of my book, it is my hope that New Market Heights will be talked about just as frequently as Antietam or Gettysburg.

How would you rate the Army of the James’s leadership at this battle?

JP: Well, they certainly experienced breakdowns at the highest levels of leadership several times before and during the battle. While Butler’s plan was well thought out, the fact that he attacked the Richmond defenses with nearly his entire army led to the inevitable friction of war that plagued large operations during the Civil War. This can be seen clearly in Maj. Gen. David B. Birney’s confusion over when he was supposed to leave the trenches of Petersburg and the ensuing night march to Deep Bottom, which led to much straggling and men breaking down under the physical strain of a forced march. Many men in the 10th Corps would only have a few hours to rest and recover before they were on the march again – this time towards New Market Heights.

Perhaps the worst leadership came from Brig. Gen. Charles Jackson Paine who led the division of USCTs slated to punch through the New Market Line. By attacking piecemeal, feeding his brigades in one at a time, he ensured much heavier casualties than would have been the case if he had attacked with his entire division. That being said, two of his subordinates – Col. Samuel A. Duncan and Col. Alonzo G. Draper – performed very well. The junior officers and NCOs performed wonderfully, as did the enlisted men – a fact that can be tragically borne out with one glance at the casualty list.

How difficult was it to piece together the narrative of this battle?

JP: Painting an overall picture of the morning attacks at New Market Heights was not especially difficult – it was getting down into the minute details that proved pretty hard. Many of the Federal documents found in the O.R. give very vague descriptions of the fighting and many of the Confederate accounts failed to distinguish between the two separate attacks. Whenever I found a detailed account of the battle I had to spend a lot of time comparing the account to what we know actually happened so that I could know where to plug that person’s testimony into the narrative. When I was unsure of what a writer was talking about, I would either include their words in a general description or exclude their account altogether. I had no trouble finding eyewitness accounts from Federal officers and Confederate soldiers – it was finding the stories left behind by the USCTs themselves that proved most difficult. Once I had amassed enough eyewitness testimony to accompany the tactical detail, I transferred the information over to master cartographer Steve Stanley who produced a beautiful set of maps for the book. I count myself very fortunate to have his work included in my first book.

Your analysis of how the battle ended differs from the standard conclusions reached by such authors as Richard J. Sommers and Barry Popchock. Briefly explain how you reached your conclusions.

JP: Richard J. Sommers, in his exceptional Richmond Redeemed: The Siege at Petersburg made the infamous claim that Butler invented the myth of a great victory at New Market Heights “and trumpeted the event for the rest of his life. Postwar historians of the black troops gladly picked up the theme and modern writers have willingly and uncritically accepted it.” Sommers went on to explain that “to go beyond citing physical courage and allege that the blacks won a major tactical victory over the vaunted Texas Brigade belies the historical record…Far from overwhelming a determined foe, Draper in effect charged into a virtually abandoned position and simply chased off a small rear guard from a position already conceded to him.” Popchock made the same argument in 1994. In conducting my own research I found no evidence of such a conspiracy on the part of Butler or any postwar historian. Butler certainly told the story of New Market Heights in his autobiography and on the floor of Congress when he was trying to help get a Civil Rights Act passed. So what? Why shouldn’t he be proud of what his troops had accomplished? I also found Confederate accounts that state quite bluntly that they were pushed out of their position – Confederate Gen. Martin Gary’s courier wrote that “[w]e ran in a panic” while another Confederate described being “routed” in his diary and saw from his vantage point that the Yankees “broke through our right and left, which caused our hasty retreat under a heavy fire.” That’s a far cry from Draper’s men being handed the New Market Line on a silver platter. But I’ll let the readers look at the evidence and draw their own conclusions.

Describe the preservation issues that New Market Heights has faced over the years. How much of the battlefield is currently preserved?

JP: Well, as you know, The Civil War Trust listed New Market Heights as one of America’s most endangered battlefields in 2009. Housing developers who could care less about the historic significance of the ground recently destroyed a portion of the Confederate position on New Market Heights itself and there is no reason to think that such wanton destruction of battlefield land won't continue unless someone steps in. The proposed expansion of Route 5 (the historic New Market Road) will eradicate even more of this hallowed ground. Fortunately, the County of Henrico has purchased an area south of Route 5 where the USCTs made their charge, but there is no public access to this site and much of the ground was destroyed by gravel mining before the county purchased the property. The county has planned to join with a local community college to create a “college in the park” on the site, but the mere act of building the campus and park would destroy large portions of what is left of the battlefield. In short, there has been much talk of preserving New Market Heights when it is politically expedient to those in local and national government – and very little when it is not. Let us hope that this unfortunate situation changes during our commemoration of the sesquicentennial.

As a longtime member and supporter of the CWT what would be your vision for the New Market Heights battlefield?

JP: First, I’d love to see a Virginia Civil War Trails marker placed off of Route 5 to accompany the State marker that was put there in 1993. Second, I’d love to see the preserved land that is now lying dormant to be converted into battlefield park where people can come and walk the hallowed ground where so many brave soldiers – both black and white – died to ensure a new birth of freedom. Finally, I’d like to see a monument to the Medal of Honor recipients placed on the battlefield. It’s far from an impossible task to accomplish, but the window of time for this to happen is closing quickly. It is for this reason that I am grateful for organizations like the Civil War Trust who are leading the charge to defend some of America’s most sacred ground.

Buy the Book: "The Battle of New Market Heights: Freedom Will Be Theirs By The Sword" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Jimmy Price is a historian, blogger, and educator. A native of Pittsburgh, PA, he has dedicated his life to the study of the American Civil War and has worked at many Civil War sites including Petersburg National Battlefield, Pamplin Historical Park, and The American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar where conducted the research for the exhibit, "Take Our Stand: The African American Military Experience in the Age of Jim Crow." He received his Bachelor of Arts in History from Virginia Commonwealth University in 2005 and his Master of Arts in Military History from Norwich University in 2009. Since then he has sought to raise awareness of African American military participation in the Civil War by writing about different aspects of their service on his award-winning weblog, The Sable Arm: A Blog Dedicated to the United States Colored Troops of the Civil War Era (sablearm.blogspot.com)

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...