Brooklyn

After compelling the British evacuation of Boston in the early months of 1776, George Washington accurately guessed that their next target would be New York City. Washington transferred his Continental Army to the city in April and May, hoping to turn back or at least severely bloody the next wave of British invaders.

The Continentals fortified the city in fits and starts. Discipline was sorely lacking among the Americans, many of whom had never been nearly so far from home and had never served in a professional military. They were awed by the arrival of the British fleet in late June. One man remarked that it looked like "all London afloat." The British infantry disembarked on Staten Island.

The British warships could dominate the river waterways that cut through New York City, rendering the American defense untenable. Nevertheless, Washington sought to fight a battle and inflict some damage before abandoning his position. His defensive arrangement, however, was fatally flawed. He split his forces between Brooklyn and Manhattan, preventing easy reinforcement or escape across the Hudson and East Rivers. Furthermore, his line atop Guan Heights did not stretch to cover the Jamaica Pass, a hole that would soon be exploited by British regulars.

On August 22, British transports moved 10,000 infantrymen to Long Island. Wrongly thinking that this was a diversion for a main attack on Manhattan, Washington did not recombine his forces to meet the new threat. On August 27, the British launched an attack on the Americans stationed at Brooklyn.

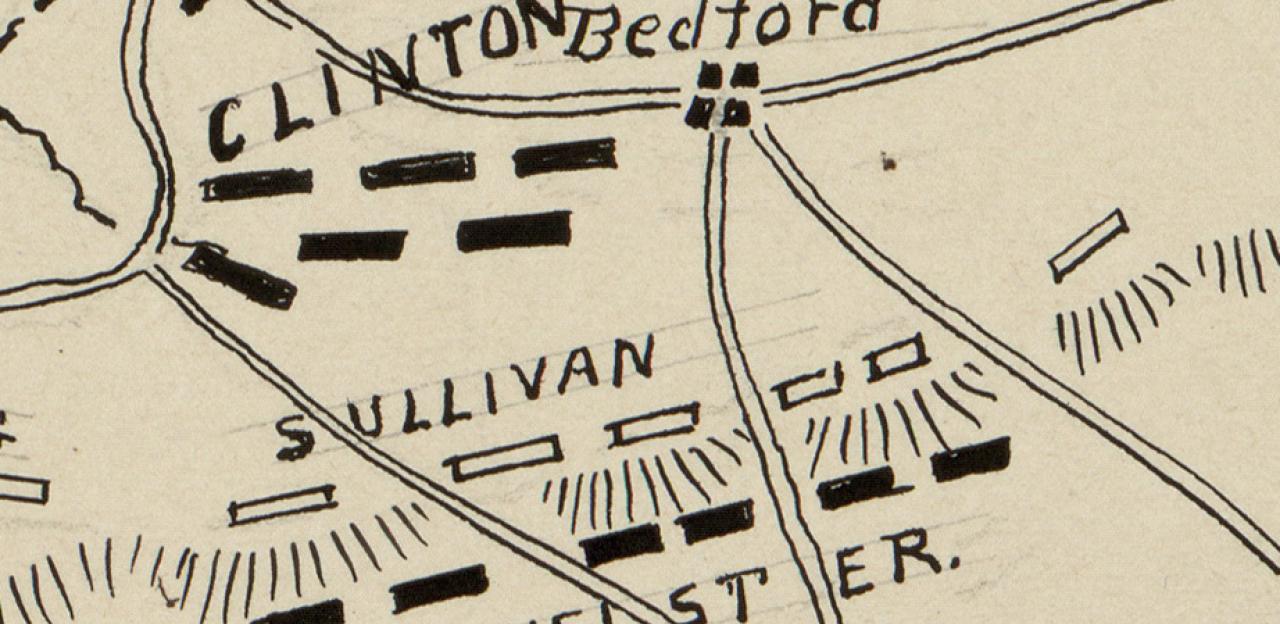

The Americans were in two lines: Guan Heights to the south and Brooklyn Heights farther north. The fighting for Guan Heights raged throughout the morning. British troops filtered through Jamaica Pass and broke through several other American positions, eventually gaining control of the ridge. The battle's bloodiest fighting occurred near "Battle Pass," where Hessian mercenaries fought the patriots hand-to-hand.

As the Americans pulled back towards Brooklyn Heights, one contingent was nearly surrounded by the onrushing British. 300-400 Maryland soldiers, now known as the "Maryland 400," counter-charged in order to buy time for their comrades to escape. More than 250 Marylanders were killed as they battled desperately against the British legions, but the rest of the army managed to escape. Washington, watching the battle, remarked, "what brave men I must this day lose."

By nightfall, the Americans were hemmed in on Brooklyn Heights with the East River behind them. British General William Howe overruled subordinates who argued for a renewed assault, instead entrenching and preparing to lay siege to Washington's army.

Washington, however, would not consent to a siege and eventual surrender. In the dark of night, he coordinated a retreat across the river without losing a single life. When the British probed the American lines, they found them empty. Despite his tactical defeat, Washington had scored strategic points by keeping his army intact. He would be hard pressed to continue that streak as the British, now very much annoyed, moved to confront him in Manhattan. The Battle of Brooklyn was the largest battle of the Revolution and the first fought after the Declaration of Independence was announced.