New York City, the second largest population hub in the American colonies, had known nothing but British occupation for seven years during the War for Independence when His Majesty’s Forces finally evacuated the city on November 25, 1783. With its access to the Hudson River and Atlantic seaboard, New York was the perfect location for a base of operations in the colonies. The British recognized this early in the war, and in September 1776, Sir William Howe’s army, after sweeping George Washington’s Continentals off of Manhattan Island, marched victoriously into the city, thus beginning its long occupation. Present with Howe was Major General Henry Clinton, a man destined to serve the longest stint as commander of the British Army in North America and call New York City his headquarters.

Henry Clinton, born in April 1730, was no stranger to the city when the British landed in Manhattan on September 15, 1776. His father, George Clinton, an admiral in the Royal Navy, was appointed governor of New York in 1741, and the family made its way to the colony in 1743. While in North America, young Henry served in an Independent New York company and on garrison duty at Fortress Louisbourg, before it was returned to the French in 1748. The following year, he was on a ship back to Great Britain, where he eventually would receive a captain’s commission in the illustrious Coldstream Guards. Afterward, he served commendably during the Seven Years’ War and on duty at Gibraltar. By 1772, he was a major general. Three years later, onboard the Cerberus with Major General Howe and John Burgoyne, Clinton made his return to America as Britain and her colonies moved to open conflict.

The loss of Boston in March 1776 forced the British to focus their military might against New York City and its 25,000 inhabitants, then the commercial and financial capital of the colonies. Clinton led a large contingent of Howe’s army and during the battle of Long Island (August 27, 1776) coordinated a massive flanking maneuver around the American left flank that rolled up the patriot line. It was a devastating blow for the Americans, who had just declared their independence from the Crown the previous month. After New York City fell, the British established it as their principal communication hub and military operations base on the eastern seaboard—essentially the other end of the 3,000-mile-long phone line that stretched across the Atlantic back home to Great Britain.

Returning to England while on leave in January 1777, Clinton received a knighthood for his actions during the battles for New York. When he arrived back in America in July, Sir Henry was given another assignment from General Howe. This new mission required Sir Henry to hold New York City while Howe opened a campaign against another major American city—Philadelphia.

As Howe’s army advanced toward the American political capital and subsequently captured it, Clinton was confronted with the prospect of assisting General John Burgoyne’s campaign against New York from Canada. The Hudson Highlands, the stretch of the Hudson River south of Albany that narrowed some forty miles above New York City, were guarded by rebel fortifications. In order to use the key water highway to link up with Burgoyne’s army, Clinton needed to clear the river of enemy obstructions. Having only 7,000 regulars and loyalists at his disposal, it was very unlikely that Clinton would be able to force his way through to Albany to make a junction with Burgoyne. A demonstration in American General Horatio Gates’ rear, however, may have been enough to force him to divert troops away from Burgoyne’s front to meet the British threat to the south.

Clinton’s advance against the Highlands fortifications began on October 3, 1777, after he received reinforcements from Great Britain. Burgoyne, eagerly waited for the news of his compatriot’s breakthrough as he, himself, was holding out to make another assault against Gates’ army near Stillwater, New York. He was all too confident that Clinton intended on marching to his assistance to defeat the Americans.

North of Stony Point on the western side of the Hudson River, 600 rebels under the command of New York governor George Clinton (no relation), defended Forts Clinton and Montgomery. With 2,100 men, Sir Henry assaulted the forts and captured them and 100 cannon on October 6. Nearly half of the American garrisons were killed, wounded, or captured, all at the loss of only 150 of the attacking force. The following day, Clinton’s army moved further north to Fort Constitution, across from West Point, and captured it as well. Still, a hundred miles away from Albany, the British thrust through the Hudson Highlands came to an end. That same day, Burgoyne was defeated in the climactic battle of the Saratoga Campaign at Bemis Heights. By the time the two generals were able to reestablish communications, it was too late. William Howe ordered Clinton to send reinforcements to Philadelphia, and Burgoyne was left on his own.

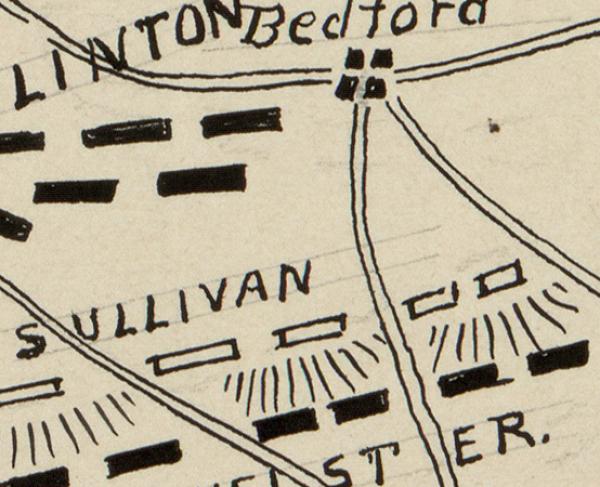

In the wake of the campaigns of 1777, Howe put in his resignation and was recalled to Great Britain. Clinton, the senior-most general in America, was appointed the new general-in-chief. With France’s entrance into the war on the side of the Americans, Clinton’s first order of business was to begin concentrating British forces on the east coast. This included the evacuation of Philadelphia and the transfer of 20,000 men back to New York City. To accomplish this, Clinton advanced his army across New Jersey to Sandy Hook in June 1778. The journey was arduous. New Jersey militiamen wreaked havoc on the advancing columns, and Washington’s army caught up to Clinton near Monmouth Court House on June 28, initiating what would become one of the largest battles of the war. Upon finally reaching their destination, the British loaded onto transports and were carried across to the city. By July 6, Clinton’s army was concentrated on Staten, Long, and Manhattan Islands.

Following Sir Henry’s return to New York City, the war in the north became stagnant as focus shifted to the southern colonies. That did not mean that Clinton, himself, was idle. The general found himself occupied with troop dispositions, foraging expeditions, and attacking American outposts outside the city and defending against enemy probes and assaults as well. Though not particularly large in scale, the military actions that took place between the Americans and British outside the city, along the Hudson, and across the river in New Jersey were bloody and vicious. Names like Stony Point, and the “Baylor Massacre,” etched themselves into the annals of Revolutionary War history.

Not all measures taken by Clinton while he was in New York involved fighting and killing. In June 1779, Sir Henry issued from his headquarters in Westchester County what became known as the “Philipsburg Proclamation.” The proclamation offered freedom to all runaway slaves who took up arms with His Majesty’s Forces. Clinton was offering freedom to those who were denied it.

Arguably the most famous event to occur in New York that directly involved Clinton transpired between May 1779 and September 1780. During this period of stalemate in the northern theater, American Major General Benedict Arnold opened communications with Clinton over the prospect of offering his services to the Crown. Major John Andre, Clinton’s adjutant-general and close subordinate served as a liaison between the general and disgruntled Arnold. In September 1780, after being appointed commander of the American forces in the Hudson Highlands, Arnold was ready to turn over the important fortifications at West Point to the British. This would give Clinton control of the river between Albany and New York City and threaten the patriot hold of the northern colonies. In exchange for this prized possession, Clinton offered Arnold £20,000 and a command in his army. The plan was thwarted, however, when Andre, carrying documents from Arnold, was captured by Westchester County militiamen on the morning of September 23. Arnold escaped to New York City and donned the scarlet uniform, but Andre was hanged as a spy on October 2.

Though viewed as a turncoat by many of his peers in his new army, Arnold was still used on multiple occasions by Clinton for raids in Connecticut and Virginia. By then the war was taking a turn for the worse for the British as they failed to reign in the southern colonies and more loyalist support. From New York, all Clinton could do was sit and wait as the combined American and French army deceived him and made its way to Virginia, surrounding General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown. Though Cornwallis had gotten himself into the trap, Clinton would serve as the scapegoat for the surrender at Yorktown and subsequent loss of America. In 1782, Sir Henry was replaced by Guy Carleton, and as he boarded a ship for home, he had left New York the final time.

Further Reading

- Southern Gambit: Cornwallis and the British March to Yorktown By: Stanley D. M. Carpenter

- Almost A Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence By: John Ferling

- The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire By: Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy

- Portrait of a General;: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence By: William Bradford Willcox

Related Battles

2,000

388