New Bern Battlefield Park, New Bern, N.C.

After raising a “Coast Division” that wasn’t particularly of the sea-faring sort, Ambrose Burnside’s fleet embarked on an expedition that looked to expand Union access to the Tar Heel State. It was safe to say that the Carolina coast was in for an awakening.

At the outset of the Civil War, Confederate forces established two Outer Banks positions, Forts Hatteras and Clark, defending the navigable inlets connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the interior sound. But their artillery was insufficient to engage the Union blockading squadrons that soon arrived off Southern coasts. In late August 1861, the war’s first combined operation of Federal army and navy forces dislodged the sparse opposition and established a strategic foothold that would not be relinquished throughout the war.

Early on the morning of August 28, despite heavy seas, a small contingent of infantry landed on the beach, while the heavy naval guns bombarded Fort Clark. In a matter of hours, their ammunition expended, the Confederate defenders abandoned Fort Clark and Union soldiers entered the fort. Although Fort Hatteras was more stoutly defended, it similarly fell the next day to a second round of overwhelming firepower — an estimated 3,000 rounds.

After disastrous defeats at Big Bethel and Bull Run, word of the Union’s nearly bloodless triumph — although some 600 Confederate prisoners were transported north to a POW camp on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor — was widely celebrated. While the Navy had compelled the surrender, Army Brig. Gen. Benjamin Butler had gone ashore to accept the unconditional surrender and politicked to wear the laurels.

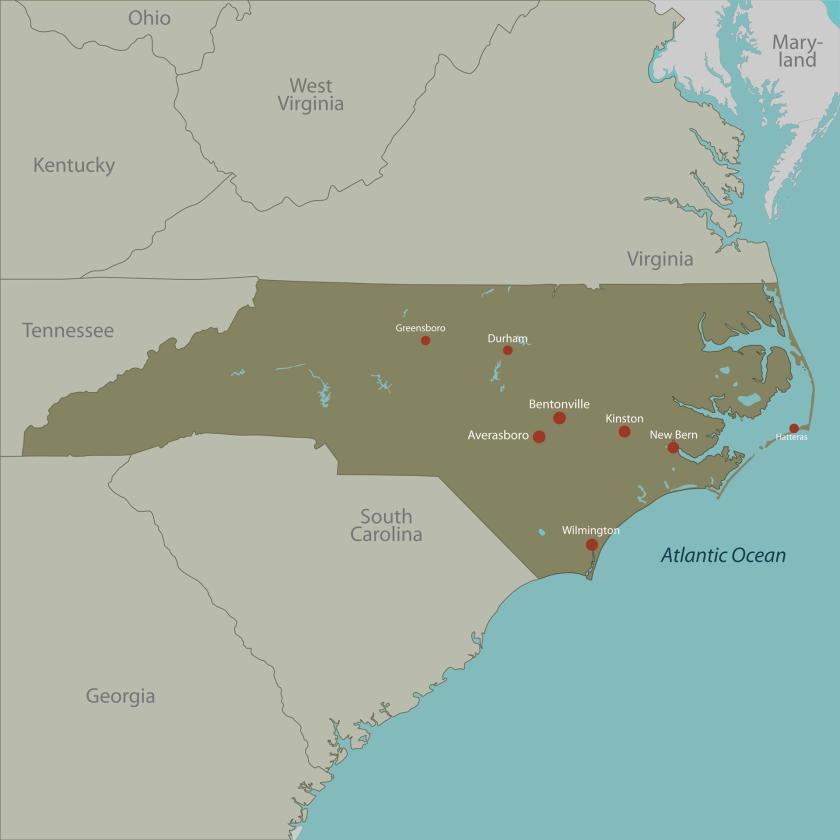

Following the success of the Hatteras Expedition, which closed the inlet to blockade running, a larger and more complex operation was planned for the spring of 1862. Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan tapped Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to organize and command this new expedition in North Carolina, and coordinate with U.S. Navy Flag Off. Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, on the joint operation. McClellan’s objectives were ambitious: Burnside and Goldsborough were to capture Roanoke Island, New Bern, Beaufort and Fort Macon and seize the railroad as far west as Goldsboro. Success in this endeavor could lead to possible strikes against other crucial points such as Raleigh and Wilmington.

What became known as the Burnside Expedition was initially a combination of ideas put forth by Goldsborough and Col. Rush Hawkins of the 9th New York Regiment. Following the capture and occupation of Hatteras, both felt that the Pamlico Sound region of North Carolina was ripe for invasion. Hawkins specifically pointed to what he perceived as strong Unionist sentiment in coastal North Carolina and the ability to recruit soldiers from the region who were loyal to the Union, an idea that both appealed to President Abraham Lincoln and made sense strategically. By controlling a large swath of coastal North Carolina, the Union could deny the Confederacy much of the area’s agricultural output.

Burnside began raising his “Coast Division” months before the expedition began, and before he even knew where it would go. Initially, he hoped to raise troops from coastal areas of New England who had some experience on the water. His troops would be transported on U.S. Army gunboats, and he felt that having men experienced at sea would be an advantage. Ultimately, his troops did come mainly from Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts, although not necessarily with any maritime background. There were some unorthodox units in the division as well, particularly the 1st New York Marine Artillery, a group that conformed to neither army nor navy standards, and is referred to in the records by numerous names. He also collected a menagerie of vessels that were converted to military usage. Burnside assembled a staff of trusted West Point classmates and personal friends, choosing Gens. John G. Foster, John Parke and Jesse Reno as his three brigade commanders. By late December 1861, Burnside’s troops were gathered and ready to move to Annapolis and, later, to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. Burnside alone knew their eventual destination.

Embarking from Hampton Roads in late January, the Union Navy experienced delays due to storms lashing the coast near Hatteras. Burnside’s troop transports finally departed on February 5. The attack on Roanoke Island began on February 7, and the island fell to Union forces the next day. The Union Navy then turned its attention toward destroying North Carolina’s fledgling navy, nicknamed the Mosquito Fleet, which, with just nine small gunboats, was no match for the 23-vessel Union naval force and was destroyed at the Battle of Elizabeth City on February 10. Union forces also burned the town of Winton on February 19. Capturing Roanoke Island and Elizabeth City ensured Union control of both the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, giving the Union military an effective foothold in the eastern part of the state from which to base future operations.

New Bern was the next target of the expedition, and Burnside’s fleet sailed from Roanoke Island on March 11 with a combined force of 11,000 men. On March 12, sailing in two parallel lines, the fleet entered the Neuse River. They anchored at the mouth of Slocum’s Creek (near present-day Havelock) and, early on the morning on March 13, shelled the shoreline and disembarked. No Confederates were posted there, but sentries upriver set bonfires to announce the Union force’s approach. The troops marched overland about two miles to reach the Beaufort-New Bern Road, then pressed on — a total of 13 miles — to New Bern. Meanwhile, the navy, under Cmdr. Stephen C. Rowan, who had replaced Goldsborough when he was recalled to Virginia for other duties, worked its way upriver, shelling and capturing numerous Confederate fortifications. The next day, March 14, after a brief defense by the Confederates, New Bern fell to the Union soldiers and remained occupied for the rest of the war. Burnside then turned his attention to the east.

From New Bern, Union troops followed the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad southeast, capturing Havelock, Carolina City and Morehead City. By March 26, Union forces had occupied Beaufort, which the Confederates had abandoned, and began planning their assault on Fort Macon, a masonry fortification on Bogue Banks that guarded the Beaufort Inlet. Union troops were ferried to Bogue Banks from March 29 to April 10. Once on the island, they erected gun emplacements and prepared to lay siege to Fort Macon. Col. Moses White, commander of the fort, was hampered by a garrison of only 403 men as well as old, smoothbore artillery pieces that lacked the range and accuracy of the Union guns. On April 25 the Union guns opened fire on the fort from land and sea. However, tempestuous seas contributed to an inability to render much damage to the fort, and the navy vessels were ultimately forced to disengage and sit out the contest when they found themselves being damaged by Confederate fire. Still, the older masonry fortification was no match for the Union’s rifled artillery, and it soon became apparent that the walls and powder magazines could be breached under heavy fire. Colonel White was forced to surrender Fort Macon.

By late April 1862, the Union controlled the coast of North Carolina from the Virginia border south to the White Oak River. Occupation forces remained in coastal North Carolina, at such locations as Roanoke Island, Plymouth, New Bern and Beaufort. Indeed, Beaufort became a coaling station for the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, making it less difficult for the Union to conduct interior raids, refuel its blockading force and supply troops. New Bern became the military and political center for the Union in North Carolina. Roanoke Island and New Bern also became home to two large freedmen’s colonies, as thousands of enslaved persons flocked to these locations to escape bondage and enjoy the protection of the Union forces.

Ultimately, the capture of Fort Macon and the end of the Burnside Expedition marked the last major military action in the state for more than two years, as the Union turned its attention to other theaters of the war. Aside from two brief forays farther inland — Foster’s Raid in December 1862 and Potter’s Raid in July 1863 — Union forces made little effort to extend their range of occupation or strike the interior of North Carolina. To the south, the port of Wilmington quickly became the most important blockade-running destination in the Confederacy, fueling Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. However, Union forces did not target Wilmington until very late in 1864 and early in 1865, despite controlling much of the rest of coastal North Carolina.