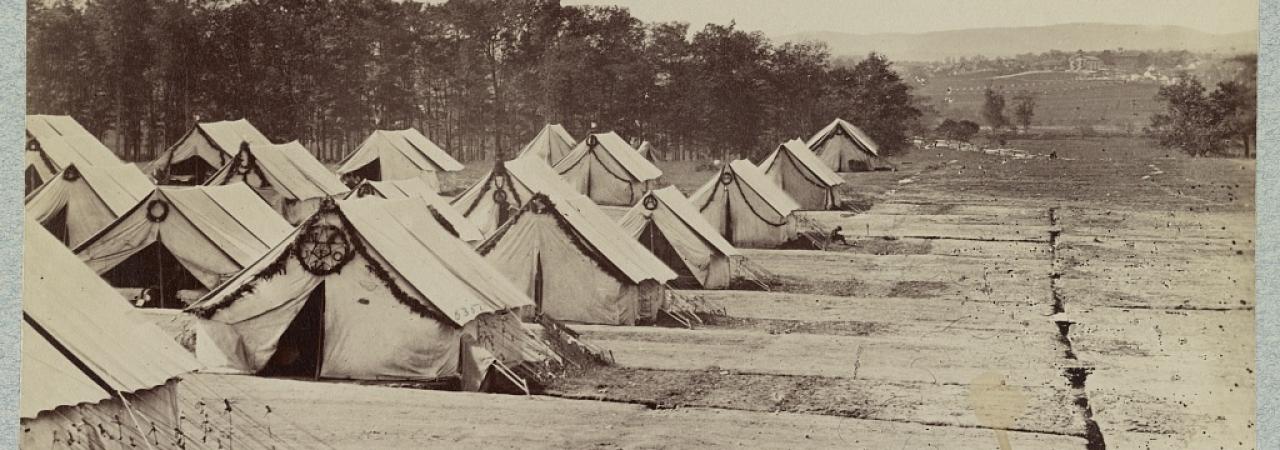

Photograph of Camp Letterman at Gettysburg, taken August 1863.

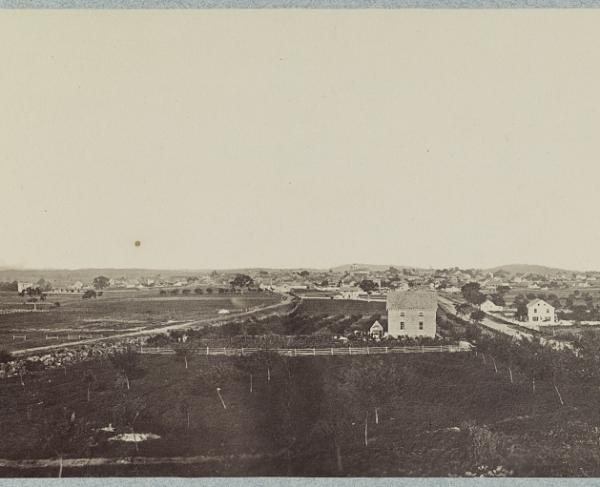

The Battle of Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. The result was a total of more than 51,000 combined casualties. About 14,000 wounded Union and 6,000 wounded Confederate soldiers were left in Gettysburg after the armies withdrew back into Virginia. To facilitate the wounded, more than sixty field hospital sites were established and spread throughout the borough and surrounding countryside. In the days following the battle, both private and public buildings, farms, and tent sites were converted into field hospitals with surgeons, nurses, and civilian volunteers trying to treat patients to the best of their ability with the limited supplies they had. However, while the aftermath of the battle was long-lasting, by July 6, the Union army was on the move again, leaving some 100 military surgeons and civilian contractors with orders to remain behind to treat the wounded soldiers who were deemed unfit to travel. In the weeks following the battle, field hospitals emptied as soldiers were either transferred to general hospitals located in cities such as Baltimore or Philadelphia. Others were transferred to a large, tented general hospital located near the battlefield called Camp Letterman, or the Letterman General Hospital, which opened on July 20th, 1863.

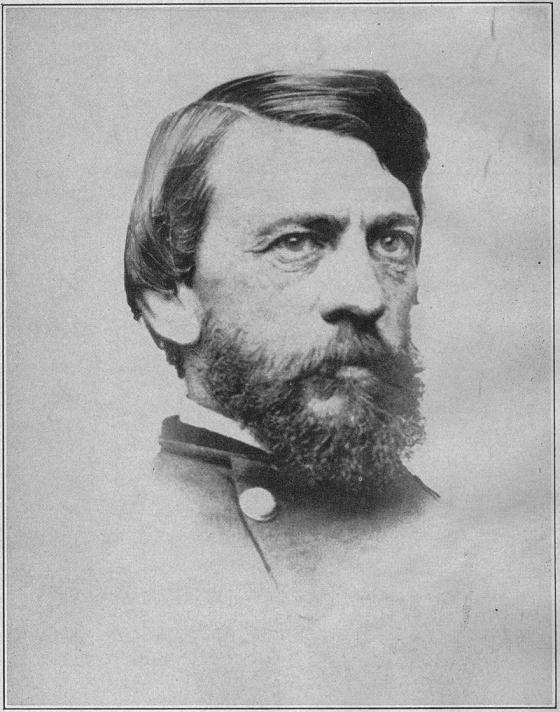

Named after the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, Camp Letterman was built on 80 acres of George Wolf’s farm, also known as “Wolf’s Woods,” located 1 mile northeast of Gettysburg on the York Pike near the Gettysburg Railroad. It was a pristine location due to its high ground, an orchard on the property that provided shade, as well as plenty of fresh spring water available. As one of the first and largest general hospitals built from the ground up, within a few months, Camp Letterman became an enormous establishment with more than 400 tents. Spread ten feet apart, each tent could house 12 patients, and each medical officer in charge of 47 patients. The hospital had the appearance of a small city with a cookhouse, officer’s row, an administrative building, and separate quarters set aside for nurses, orderlies, attendants, and more. Volunteers from the U.S. Christian Commission erected a store and lodge tents near the site where they assisted around the hospital, prepared meals, and aided with supplies. Camp Letterman also contained a dead house, an embalming pavilion, and a cemetery with sections dedicated to Union and Confederate soldiers.

Not only was Camp Letterman large enough to have the appearance of a city, but it was also a well-functioning operation. Surgeons treated patients for bullet wounds and broken bones, as well as treated infections and illnesses. Both the United States Christian Commission and United States Sanitary Commission had delegations headquartered at Camp Letterman and assisted with administering supplies and nursing soldiers. Attendants, cooks, and laundresses cleaned the wards, washed the clothes and sheets, and cooked the meals. Guards kept watch not only over the supplies and policed the area, but watched over wounded enemy soldiers. One volunteer nurse from Gettysburg, Sophronia E. Bucklin, recalled what a typical day was like at the general hospital:

Stimulants were first given out early each morning, followed by special diets which were prepared by the cooks. Next came the wound dressers who made their rounds, each being assigned to a particular section of each ward. Beef tea was passed out three times a day, the stimulants three times, and the extra diet three times, making nine visits total…The soldiers’ faces were washed, their hair combed, and sponge baths were performed by only the male nurses, and extra drinks administered as required.

The days at Camp Letterman became monotonous with convalescing soldiers following the same routine day in and day out. To try to break this monotony, on September 23, a banquet occurred. Patients and hospital staff, both Union and Confederate enjoyed a feast that consisted of more than 4,000 chickens, 20 hams, 50 beef tongues, oysters, pies, ice cream, and more. As a part of this festival, there were minstrel shows, music, and foot races as well as a greased poll and “gander pulling” contests.

While Camp Letterman was considered incredibly well-run, clean, and efficient in the treatment of its soldiers, it was not always a place of feasting and merriment. In October 1863, a guard from the Pennsylvania Militia named Frank Stoke remarked:

As high as seventeen die per day…Those who die…are buried in the field south of the hospital; there is a large grave-yard there already. The dead…are nearly all Confederates. …the amputated limbs are put into barrels and buried and left in the ground until they are decomposed, then lifted and sent to the Medical College at Washington. A great number of buries are embalmed here and sent to their friends. Close to the grave-yard is a large tent called the dead-house, another where they embalm.

As the number of wounded decreased as summer turned to fall, the hospital was closed on November 20, 1863, and all patients were transferred to other institutions. As the tents were taken down, Sophronia Bucklin wrote “each bare and dust-trampled space marking where corpses had lain after the death-agony was passed, and where the wounded had groaned in pain, tears filled my when I looked on that great field, so checkered with the ditches that had drained it dry.” By the time Camp Letterman finally shut down over 14,000 Union soldiers and 6,800 Confederate soldiers received treatment, but more than 1,200 soldiers died because of their wounds, infection, or disease.

Although Camp Letterman was the largest tented hospital site during the Civil War, little of the historic location remains today. Many of the soldiers who died and were buried at Camp Letterman were reinterred in the years following the war, with the Union moved to the nearby national cemetery and Confederate soldiers reinterred throughout the South. While the area remained a rural field for many years, today the site located off Lincoln Highway is a shopping center. While only a few interpretive markers illuminate the history of the Camp Letterman on site, Camp Letterman is imperative to the story of Gettysburg and the history of military medicine as we know it today.

Further Reading:

- A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War, By: Sophronia E. Bucklin

- A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg, the Aftermath of a Battle, By: Gregory A. Coco

- Bullets and Bandages: The Aid Stations and Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, By: James Gindlesperger

- Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care, By: Scott McGaugh

- Where Have All the Hospitals Gone? The Aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, By: Lori Tillia-Meeker

Related Battles

23,049

28,063